If you’ve ever driven through the winding gaps of the New River Gorge or stood atop a ridge in Logan County, you’re looking at a landscape that is basically a honeycomb. Beneath those ancient, rolling hills lies a sprawling, invisible empire. Finding a reliable map of west virginia coal mines isn't just a niche interest for history buffs; it’s a critical tool for engineers, real estate buyers, and anyone curious about why certain patches of ground in the Mountain State seem to behave the way they do.

Coal built West Virginia. That’s not hyperbole. From the boomtowns of the early 1900s to the high-tech longwall operations of today, the geology of the state has dictated its economy and its physical shape. But because mining has been happening here for over 150 years, the "map" isn't just one document. It’s a massive, shifting layer cake of data that tracks where men worked by candlelight a century ago and where massive shearers are cutting coal today.

The Reality of Mapping an Invisible Industry

The first thing you’ve got to realize is that a "complete" map doesn't really exist in a single, static image. Think of it more like a digital archive. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) and the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey (WVGES) are the gatekeepers of this data. They manage the West Virginia Coal Bed Mapping Program (CBMP), which is arguably the most ambitious effort to digitize every known seam and entry point in the state.

Why is it so hard to get right?

Well, honestly, the old-timers weren't always great at record-keeping. In the late 1800s, "dog hole" mines—small, unlicensed operations—popped up everywhere. These guys would dig into a hillside, pull out enough coal to heat a town or fuel a small forge, and then move on when the seam got thin or the roof got sketchy. They didn't file GPS coordinates. They didn't submit five-year plans to a federal agency.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and we’re still dealing with the legacy of those unmapped voids. When a road sinks or a backyard suddenly develops a "glory hole," it’s often because of a mine that wasn't on the official map of west virginia coal mines. Modern mapping relies on a mix of scanned historical paper maps, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), and active permit data to try and fill in those blanks.

Where the Coal Actually Is: Breaking Down the Regions

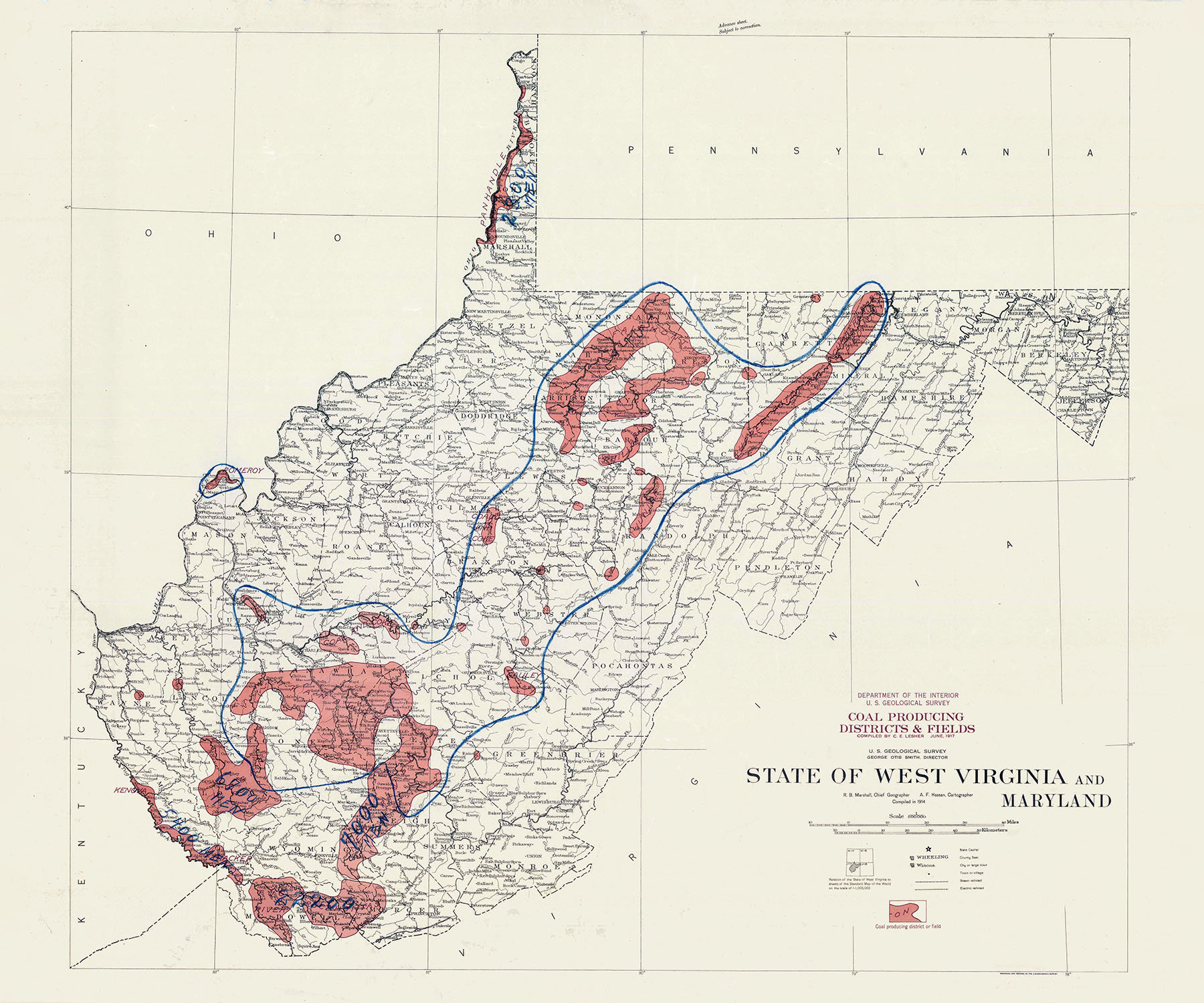

West Virginia is generally split into two major coalfields, and the maps for each look wildly different because the geology isn't the same.

The Northern Coalfield

This area is dominated by the Pittsburgh Seam. It’s thick. It’s consistent. It’s the "Old Reliable" of the coal world. Because the seam is so uniform, the maps here look like massive, organized grids. In counties like Monongalia, Marion, and Marshall, you’ll see huge blocks of "mined out" areas on a map. This is where longwall mining happens—a method where a massive machine shears across a wide face of coal, allowing the roof to collapse behind it in a controlled way.

✨ Don't miss: Les Wexner Net Worth: What the Billions Really Look Like in 2026

The Southern Coalfield

Now, look at a map of Kanawha, Boone, Logan, or Mingo counties. It’s a mess. A beautiful, chaotic mess. The seams here—like the Pocahontas, Sewell, and No. 2 Gas—are often thinner and high-quality metallurgical coal used for steelmaking. The terrain is steeper. The maps here show "contour mining," where companies followed the coal seam around the edge of a mountain like a ring on a finger. You’ll see "drift mines" where they poked into the side of the hill rather than digging a deep vertical shaft.

How to Access a Real Map of West Virginia Coal Mines Right Now

If you're looking for these maps because you're worried about mine subsidence or you're doing geological research, don't just use Google Images. You’ll get outdated low-res JPEGs.

You need to head to the WVDEP Mining GIS Database.

- The Interactive Map Gallery: This is their primary web-based tool. It lets you toggle layers for active permits, abandoned mine lands (AML), and specific coal seams. You can zoom into a specific parcel of land and see if there are "underground workings" beneath it.

- WVGES Coal Bed Mapping Program: This is where the heavy-duty geological data lives. If you want to know the thickness of the coal or the elevation of the seam, this is your source.

- Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) Data: For active mines, federal data provides a different lens, focusing on production and safety stats rather than just the physical footprint.

It's kinda wild when you look at the "Coal Mining and Reclamation" layer on a GIS map. You’ll see areas that look like Swiss cheese. These are the "room and pillar" mines. Miners leave pillars of coal behind to hold up the roof. On a map, these look like a series of tiny black squares inside a larger void.

The Subsidence Factor: Why Maps Matter to Homeowners

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: mine subsidence. This is when the ground above an old underground mine shifts or sinks.

In West Virginia, the law is pretty specific about this. If you’re buying a house in a "minable" area, your insurance agent is probably going to mention the West Virginia Mine Subsidence Insurance Fund. Why? Because many of the maps we have are "best guesses" for mines closed before the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA).

Before '77, regulations were... let's say "loose."

🔗 Read more: Left House LLC Austin: Why This Design-Forward Firm Keeps Popping Up

If you're looking at a map of west virginia coal mines and you see a "dashed" line or a faded hatched area, that usually means the exact boundaries of the mine are unknown. Engineers use these maps to create "buffer zones." If you’re building a multi-million dollar school or a bridge, you don't just look at the map; you drill core samples to make sure there isn't a 20-foot void 50 feet below your foundation.

Digital vs. Historical: The Evolution of the Search

There’s a certain romance to the old maps. If you go to the West Virginia and Regional History Center at WVU, you can find hand-drawn maps from the early 20th century. They’re works of art—ink on vellum, colored with pencils to show different elevations.

But for practical use today, it's all about the GIS (Geographic Information Systems).

The state has been working for years to "georeference" old paper maps. This basically means taking a scanned image of a map from 1920 and stretching it digitally so it perfectly overlays with modern GPS coordinates. It’s a tedious process. Sometimes the old maps are off by hundreds of feet because the original surveyors were using chains and transits in a thick forest during a rainstorm.

What the Map Doesn't Tell You

A map can show you where the coal was. It can show you who owned the permit. It can even tell you how deep the shaft was.

But it won't tell you the condition of the mine.

An "abandoned" mine on a map could be perfectly dry and stable, or it could be a pressurized reservoir of millions of gallons of "mine water" (which is usually highly acidic). This is why the WVDEP’s Abandoned Mine Lands program is so busy. They use the maps to hunt down old portals that are leaking orange water into streams or venting methane gas near residential areas.

💡 You might also like: Joann Fabrics New Hartford: What Most People Get Wrong

The map is a snapshot of an industry that is currently in a state of massive transition. While the number of active mines has plummeted over the last decade, the physical footprint remains. Those voids aren't going anywhere.

Actionable Steps for Using This Data

If you need to find information about a specific location, don't settle for a surface-level search.

- Check the WVDEP Map Viewer first. It’s the most user-friendly way to see if there is an underground mine (UG) or a surface mine (S) near your location.

- Search by Permit Number. If you see a permit like "S-3001-01," you can look up the specific history of that operation, including when it was reclaimed and who was responsible for it.

- Verify with the County Clerk. Sometimes local land records have old "severed mineral rights" maps that never made it into the state’s digital database.

- Consult a Professional. If you are doing construction or buying land, hire a surveyor or a geological engineer who specializes in West Virginia’s coal geology. They have access to proprietary data and can interpret the nuances of a GIS layer that a layperson might miss.

The map of west virginia coal mines is a living document. Every time a new subsidence event is recorded or an old company archive is donated to a university, the map gets a little more accurate. It’s the blueprint of the state’s past and a cautionary guide for its future.

To get started with the official data, visit the WVDEP’s GIS Server and look for the Mining and Reclamation section. That’s where the real story is hidden.

Search for the specific seam names like "Pittsburgh," "Eagle," or "Sewell" to narrow down your results. Knowing the seam is often the key to finding the right historical records, as many old maps were filed by the seam name rather than the company name.

Always cross-reference. A "reclaimed" surface mine on a map might look like a flat field today, but it doesn't have the same soil stability as "virgin" ground. If you’re looking at a map for gardening or farming, "reclaimed" usually means the topsoil is thin and the rock underneath is fragmented. Understanding these layers is the only way to truly know what's happening under your feet in West Virginia.