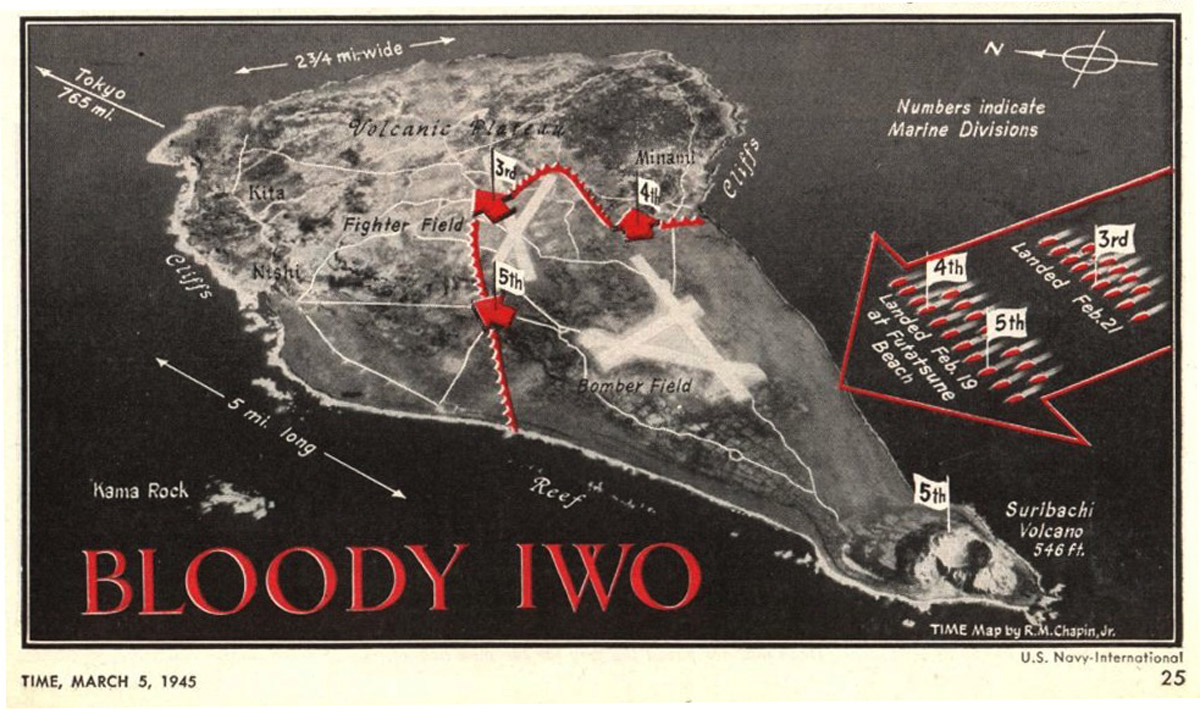

If you look at a map of Iwo Jima today, it looks like a pork chop. Or maybe a teardrop if you’re feeling poetic. But back in February 1945, for the 70,000 Marines staring at it from the decks of transport ships, it just looked like hell. It’s a tiny speck. Honestly, it’s barely eight square miles of volcanic sand and jagged rock sitting about 750 miles south of Tokyo. You could walk across the widest part of the island in an afternoon if nobody was shooting at you. But for five weeks, it was the most contested piece of real estate on the planet.

Most people think they know the island because of that one photo of the flag on Mount Suribachi. But if you actually study the topographic layout, you realize the flag-raising happened on day four. The battle lasted thirty-six days. That means the "map" most of us have in our heads is basically just the bottom left corner of the actual story.

The Vertical Nightmare of Mount Suribachi

Suribachi is the landmark everyone recognizes. It’s that 554-foot extinct volcano at the southern tip. On a map of Iwo Jima, it looks like a clear, distinct objective. Easy, right? Take the hill, win the island.

Not even close.

The Japanese commander, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, knew he couldn't stop the Marines from landing on the beaches. The sand was too soft—it was basically ground-up volcanic ash that men sank into up to their knees. So, he didn't even try to hold the shoreline. Instead, he turned the entire mountain into a literal honeycomb. We're talking about eleven miles of tunnels. When you look at a flat map, you don't see the verticality. You don't see the seven stories of rooms carved into the rock, the ventilation shafts, or the hidden artillery pieces that could slide out, fire a round, and disappear back into the mountain before a destroyer could even find the range.

The Marines were essentially fighting a ghost city. They’d "clear" a ridge on the map, move forward, and then get shot in the back because the defenders had simply moved through a tunnel to a different opening. It was frustrating. It was deadly. It was a three-dimensional chess match where the Americans only had two-dimensional maps.

Why the Airfields Dictated Everything

If you look at the center of any military map of Iwo Jima, you’ll see three distinct strips. These were the airfields: Motoyama No. 1, No. 2, and the unfinished No. 3. This is why the battle happened. Period.

The US Army Air Forces were flying B-29 Superfortresses from the Marianas to bomb Japan. It was a long flight—about 3,000 miles round trip. If a plane got hit or had engine trouble, there was nowhere to land. They just ditched in the Pacific. Iwo Jima was perfectly placed to be an emergency landing strip. Plus, the Japanese were using the island to launch fighter planes to intercept those bombers.

🔗 Read more: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

The "Meat Grinder."

That’s what the Marines called the area around Airfield No. 2. On a paper map, it’s just a flat, open space. In reality, it was a killing zone surrounded by jagged limestone outcrops called "The Gorge" and "Hill 382." Because it was open ground, the Marines had no cover. They had to run across the runways while Kuribayashi’s men watched them from reinforced concrete pillboxes that were almost invisible against the gray landscape.

The Map the Americans Didn't Have

Here is the thing that really gets me: the US intelligence maps were almost entirely wrong about what was underground. They had aerial photos, sure. They could see the pillboxes and the trenches. But they had no idea that the Japanese had moved their entire defense system into the earth.

- 11 miles of tunnels (planned 17 miles).

- Hospital wards underground.

- Command centers 75 feet deep.

- Geothermal heat that made the tunnels 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Imagine trying to navigate using a map that only shows the roof of a building while the enemy is living in the basement and the air vents. That was Iwo Jima. The "map" was a lie because the terrain had been artificially altered. The Japanese didn't just build bunkers; they reshaped the volcanic ridges to create overlapping fields of fire. If you moved to take out one machine gun, three others had you in their sights.

The Sulfur and the Steam

The island’s name literally means "Sulfur Island." It’s not just a name. If you go there today—and it's hard to get there, since it's a closed Japanese military base—the smell of rotten eggs is everywhere. The ground is hot. You can dig a hole in the sand and it'll burn your hand.

During the battle, this meant the Marines couldn't dig foxholes for cover. If they dug too deep, the heat and fumes would drive them out. So, the map of Iwo Jima isn't just a guide to geography; it's a guide to a geological nightmare. The north end of the island is full of "badlands"—broken, jagged rocks and deep crevices that look like the surface of the moon.

Bill Semich, a veteran who spoke about the terrain, once noted that you couldn't even call it "dirt." It was cinders. Imagine trying to run up a slide made of marbles while carrying 80 pounds of gear. That’s the landing beach.

💡 You might also like: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

Understanding the "Pork Chop" Layout

To make sense of the movement, you have to divide the map into three parts.

The southern end is Suribachi. The Marines landed on the southeastern beaches right next to it. Their first job was to cut the island in half. They did this on the first day, reaching the western shore. Then, one group turned left to go up the mountain. Everyone else turned right to head into the teeth of the Japanese defense in the north.

The northern part of the map is where 90% of the casualties happened. It’s where the "Meat Grinder" was. It’s where "The Blockhouse" and "Cushman's Pocket" were located. These names aren't on official geographic maps, but they are etched into the history of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions.

General Kuribayashi didn't stay on Suribachi. He stayed in the north. He died there, though his body was never found. His headquarters was a massive cave complex near the northern tip at Kitano Point. When you look at the map of Iwo Jima, that northern point is the end of the line. By the time the Marines reached it, they were decimated. Some companies were down to 10% of their original strength.

How to Read a Map of the Battle Today

If you're looking at a historical map, look for the "Phase Lines." These are the lines drawn by planners to show where they thought the troops would be each day.

They were off by weeks.

The planners thought the island would fall in five days. It took thirty-six. When you compare the "Planned" lines to the "Actual" lines on a map of Iwo Jima, you see the sheer scale of the resistance. The progress was measured in yards, not miles. On some days, the frontline moved less than the length of a football field.

📖 Related: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

The most accurate map isn't the one with the neat arrows. It's the one that shows the density of the Japanese "Honeycombed" defenses. There were over 750 identified pillboxes and bunkers on that tiny rock. That’s about 100 per square mile. You couldn't sneeze without hitting a fortification.

Modern Day Iwo Jima (Iwo To)

In 2007, the island’s name was officially changed back to Iwo To, which is what the original inhabitants called it before the war. If you look it up on Google Maps now, you’ll see a single paved runway. That’s the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force base.

You can see the black sand beaches from the satellite view. They still look lonely. There are no hotels, no gift shops, and no residents. It is a massive graveyard. Even though many remains have been recovered, thousands of Japanese soldiers are still entombed in those tunnels that aren't visible on your screen.

Navigating the Legacy

Understanding the map of Iwo Jima isn't just about military strategy. It’s about realizing how much the ground itself dictates history. The US needed those airfields. By the end of the war, over 2,200 B-29s had landed there. That’s roughly 27,000 airmen who might have died at sea if that tiny "pork chop" island hadn't been taken.

But the cost was 6,800 American lives and nearly 20,000 Japanese lives.

When you look at the map, don't just see the lines and the elevations. See the heat, the sulfur, the black ash, and the impossible courage it took to move an inch on a piece of land that seemed designed to kill you.

What you should do next to understand the geography better:

- Find a topographic map: Standard road-style maps are useless here. You need to see the "contour lines" to understand how Suribachi dominated the landing beaches.

- Overlay the tunnel systems: Look for specialized historical maps that overlay the Japanese tunnel network onto the surface map. It's the only way to see why "clearing" a hill didn't actually mean it was safe.

- Check the 1945 aerial surveys: The US National Archives has the original photos taken by reconnaissance planes. Comparing those to the actual ground reality found by the Marines is a masterclass in the limitations of intelligence.

- Look at the "Green Beach" and "Red Beach" sectors: Notice how narrow the landing zone was. The entire invasion force was squeezed into a tiny strip of sand, making them sitting ducks for the artillery on the heights.

The map is the story. If you can't see the ridges and the caves, you can't see the battle. It was a fight for a rock, on a rock, and often inside a rock.