You’ve probably seen the map of the Khyber Pass in a dusty history textbook or maybe on a flickering screen during a news segment about regional instability. It looks like a simple squiggle. A jagged line cutting through the Spin Ghar mountains, connecting Pakistan and Afghanistan. But honestly, a two-dimensional drawing doesn't even come close to explaining why this 53-kilometer stretch of road has been the literal pivot point of world history for three thousand years.

It’s rugged. It’s narrow. In some places, the limestone walls soar up 1,000 feet, making you feel like a tiny speck between the peaks of the Hindu Kush. If you’re looking at a map of the Khyber Pass, you’re looking at the gateway to the Indian subcontinent. It’s the path Alexander the Great took. It’s where the British Empire learned some very painful lessons. Today, it’s a logistics nightmare and a geopolitical chess piece all rolled into one.

The Geography of a Legend

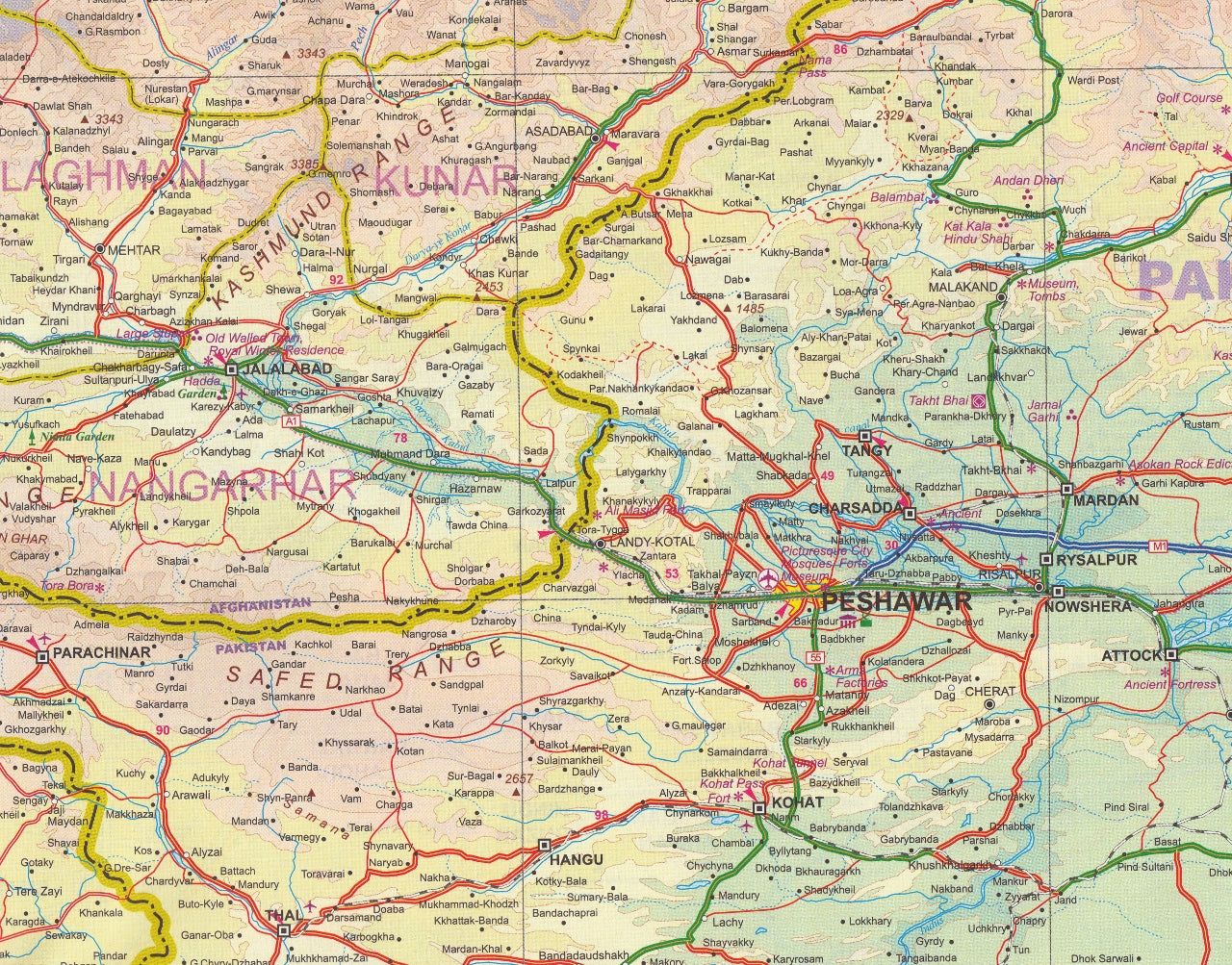

Zoom in on the map of the Khyber Pass and you’ll find the starting point at Jamrud, just west of Peshawar in Pakistan. From there, the road winds up, gaining elevation until it hits the highest point at Landi Kotal. Then, it drops back down toward the border at Torkham.

Most people think it’s just one road. It isn't.

Historically, there were multiple tracks. There’s the main highway, which is now paved and heavy with "colorful" Bedford trucks hauling everything from coal to electronics. Then there’s the Khyber Railway. This thing is a marvel of British engineering, finished in 1925, featuring 34 tunnels and 92 bridges. It’s rarely operational for tourists these days due to security and maintenance issues, but its presence on the map shows just how much effort humans have put into conquering this terrain.

The pass narrows significantly at a place called Ali Masjid. This is the "throat." Here, the pass is barely 15 meters wide. Imagine an invading army—or even just two passing semi-trucks—trying to squeeze through that. It’s a natural bottleneck that has determined the outcome of more wars than almost any other geographical feature on Earth.

Why the Map of the Khyber Pass Keeps Changing

Political boundaries in this part of the world are... complicated. If you look at an official map of the Khyber Pass, you see a clear line at Torkham marking the border between Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province. But the local tribes, primarily the Afridi and Shinwari clans of the Pashtuns, have historically viewed these lines as suggestions rather than hard realities.

For decades, this area was part of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). It was a "buffer zone" where the Pakistani government had limited reach. In 2018, these areas were officially merged into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. This changed the administrative map, but the cultural map remains much more stubborn.

You’ve got to understand the Durand Line. This 1893 boundary, drawn by Sir Mortimer Durand, splits the Pashtun heartland in two. Afghanistan has never really formally recognized it. So, when you look at a map of the Khyber Pass, you aren't just looking at a road; you're looking at a site of perpetual diplomatic friction.

The Logistics of the Modern Pass

It’s not just about history. It’s about money.

The Khyber Pass is a primary artery for the Afghan Transit Trade. Thousands of containers move through here every week. If you were to look at a real-time satellite map of the Khyber Pass right now, you’d likely see a massive line of trucks backed up at the Torkham border crossing. Sometimes the line stretches for miles.

The terrain makes it difficult to expand. You can’t just "add a lane" when you’re dealing with sheer rock faces and deep ravines. The Pakistani government has invested in the Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) to improve the infrastructure, but progress is slow because, well, moving mountains is expensive.

Misconceptions You Might Have

People often think the Khyber Pass is a lawless wasteland. That’s sort of a trope.

📖 Related: Extended forecast for Clearwater Florida: Why it's not always "shorts weather"

Is it dangerous? It can be. Security is tight, and you usually need a specialized permit (and often an armed escort) if you’re a foreigner trying to traverse it. But it’s also a place of incredible hospitality. The Pashtunwali code of honor means that once you are a guest, you are protected.

Another mistake: thinking the pass is "unconquerable."

Actually, plenty of people conquered it. Ghengis Khan, Babur, Nadir Shah. The trick wasn't getting through the pass; the trick was holding it. You can't control the map of the Khyber Pass without the cooperation of the people who live in the crags above the road. The British learned this during the Anglo-Afghan Wars. They could march through, sure, but the moment they stopped watching the ridges, things went south.

Seeing it for Yourself

If you’re a traveler or a history buff wanting to see the map of the Khyber Pass in real life, you start in Peshawar.

- The Bab-e-Khyber: This is the iconic gate at the entrance of the pass. It’s the "Instagram spot" of the region, built in 1964.

- Jamrud Fort: It looks like a giant battleship made of mud and stone.

- The Sphola Stupa: This is a 2nd-century Buddhist ruin. It’s a weird, beautiful reminder that this wasn’t always a site of Islamic struggle; it was once a major path for the spread of Buddhism into China.

- Landi Kotal Bazaar: The highest point. It’s a bustling market where you can find anything from smuggled tea to car parts.

The reality of the Khyber Pass is that it’s a living, breathing entity. A map gives you the "where," but it doesn't give you the "why." The "why" is the smell of diesel fumes mixed with mountain air, the sight of ancient forts guarding modern paved roads, and the weight of thousands of years of footsteps echoing in the silence of the cliffs.

Actionable Steps for Navigating the Khyber Pass Region

If you are planning to explore or study this area, keep these practical points in mind to ensure you get the full picture beyond a basic Google search.

- Secure Proper Documentation: If you are a non-Pakistani citizen, you cannot simply drive into the pass. You must apply for a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the Pakistani Ministry of Interior. This process can take weeks, so plan well in advance of your trip to Peshawar.

- Consult Local News, Not Just Maps: Because the Torkham border frequently closes due to political disputes or security concerns, check live updates from local outlets like Dawn or The Express Tribune. A map won't tell you if the border is shut down for the next 48 hours.

- Use Topographic Layers: When viewing a map of the Khyber Pass digitally, toggle on the "Terrain" or "Topographic" layer. Understanding the elevation change—climbing from about 600 meters in Peshawar to over 1,000 meters at Landi Kotal—is crucial for understanding the military and logistical history of the region.

- Hire a Local Guide: The nuances of tribal territories (the "Khels") aren't marked on standard maps. A local guide from Peshawar can explain which tribe controls which section of the ridges, which is essential for both safety and historical context.

- Study the Railway Path: For the best "engineering" view, find a map that specifically highlights the Khyber Railway. Even if the trains aren't running, following the track’s path through the 34 tunnels provides a better sense of the pass’s verticality than the main road does.

The Khyber Pass remains one of the few places on earth where geography still dictates the terms of human existence. Whether you’re studying it for a history project or planning a high-stakes travel itinerary, treat the map as a starting point, not the final word.