So, you’re staring at a lab sheet or a digital PDF, and you need the examining the fossil record answer key because, let's be real, trying to piece together 3.5 billion years of biological history on a Tuesday afternoon is a lot. It’s not just about matching Bone A to Era B. Honestly, most students and teachers get bogged down in the sheer scale of it all. You’ve got trilobites, you’ve got strange fern-like imprints, and suddenly you’re expected to explain the difference between punctuated equilibrium and gradualism like you’re Charles Darwin’s personal assistant.

Fossils are messy. They aren't perfect.

Most of the time, when people search for an answer key, they’re looking for a shortcut to the "Marsupial vs. Placental" distribution patterns or the specifics of the Archaeopteryx transition. But if you just copy-paste the answers, you're going to miss the actual logic that makes this stuff click. The fossil record is essentially a giant, broken jigsaw puzzle where 90% of the pieces were thrown in the trash by geological time. We have to work with what's left.

Why the Examining the Fossil Record Answer Key is Hard to Find

Searching for a specific key is like hunting for a needle in a haystack because there are roughly a dozen different versions of this specific lab. Some are based on the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) curriculum, while others are adaptations of the classic "Strategram" activities. You might be looking for the one that uses those little paper cutouts of fictional "Crinoid" species, or maybe the one focusing on real-world whale evolution.

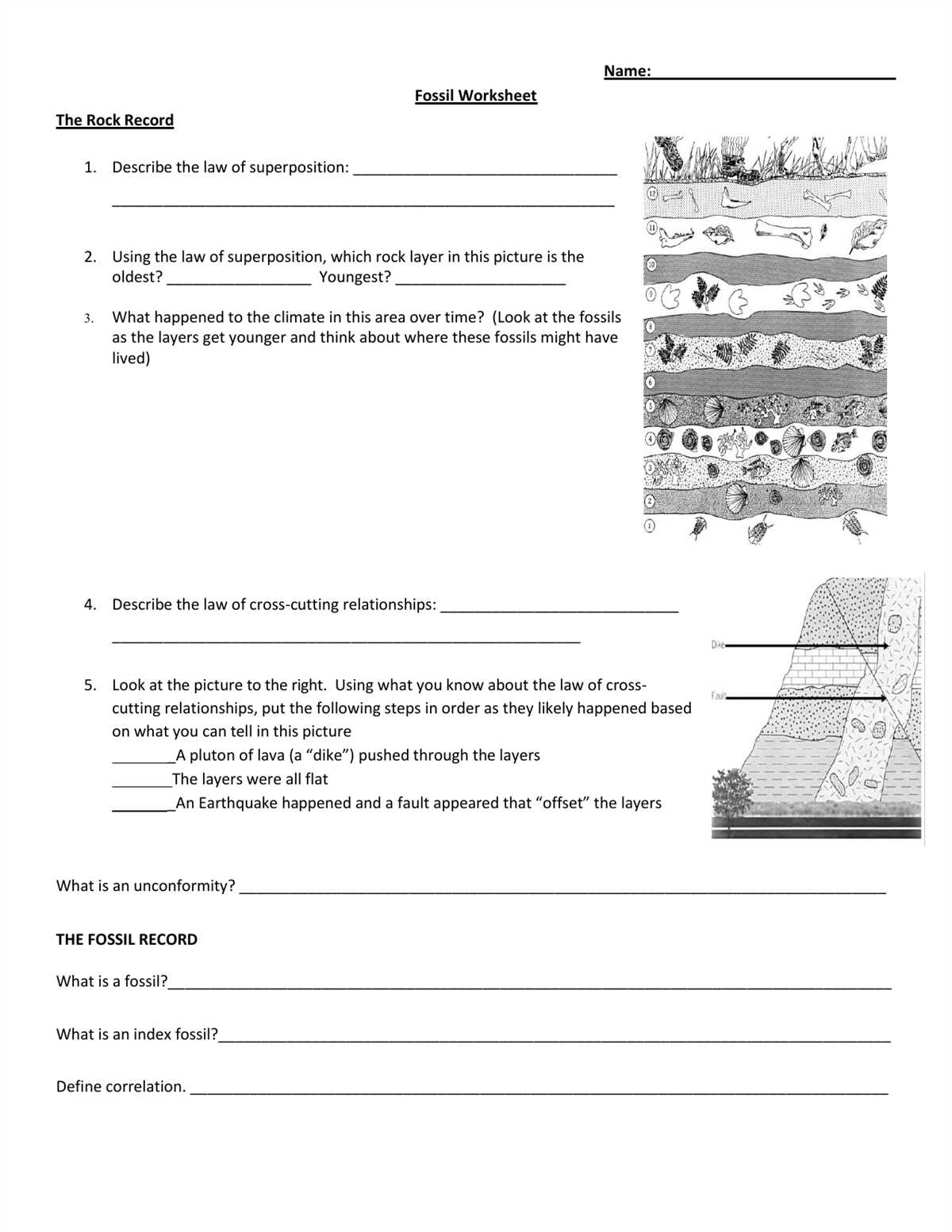

The most common version asks you to arrange fossils in chronological order based on rock layers. This is stratigraphy. It’s the bread and butter of geology. If you find a shell in a layer of limestone that’s deeper than a layer of sandstone, the shell is older. Simple, right? Except when the Earth’s crust folds over on itself like a cheap lawn chair. That’s called an unconformity, and it’s why your answer key might look "wrong" even when you’re looking right at the data.

✨ Don't miss: Cheesy Bread Pull Apart: Why Your Version Is Probably Dry (And How To Fix It)

The Problem with Index Fossils

You’ll definitely see questions about index fossils. These are the celebrities of the prehistoric world. To be a good index fossil, a species had to live for a very short period of time but be spread out everywhere. Think of it like a specific iPhone model. If you find an iPhone 4 in a trash heap, you know exactly what year that trash was buried. Trilobites are the iPhone 4 of the Paleozoic. If your answer key asks why a specific organism is a "good" index fossil, the answer is always: widespread geographically and limited geologically.

Breaking Down the Patterns of Evolution

When you’re looking at the data, you’re usually trying to see how one thing turned into another. This is where people get tripped up on the vocabulary.

Gradualism is the idea that evolution happens like a slow crawl. Small changes over millions of years. If your fossil chart shows a shell slowly getting wider and wider over five different rock layers, that’s your answer.

On the flip side, punctuated equilibrium is much more dramatic. Everything stays the same for a long time (stasis), and then—boom—a massive change happens almost overnight, geologically speaking. This usually happens because of a massive environmental shift, like a volcano or a climate flip. If your lab shows a sudden jump in species shape with no "in-between" fossils, you're looking at punctuation.

🔗 Read more: bareSkin Complete Coverage Serum Concealer: Why This Cult Favorite Still Matters

Wait. Is it actually "missing" or just not preserved?

That’s the nuance. Most organisms don't become fossils. They rot. They get eaten. They get crushed. To become a fossil, you have to die in exactly the right spot—usually mud or volcanic ash—and stay undisturbed for eons. Soft-bodied things like jellyfish? Forget about it. We barely have any record of them. We’re mostly looking at the history of things with teeth, shells, and bones.

Real Examples from the Fossil Record

Let’s talk about whales. If your examining the fossil record answer key mentions Basilosaurus or Pakicetus, you’re looking at one of the coolest transitions in science. Pakicetus was basically a four-legged land dog-thing that lived near the water. Over millions of years, the nostrils moved to the top of the head (the blowhole), and the legs turned into flippers.

If you have to identify "vestigial structures" in whales, the answer is the pelvic bone. Modern whales still have tiny, useless hip bones floating in their blubber. It’s a leftover from when their ancestors walked on land.

- Law of Superposition: Older stuff is on the bottom.

- Transition Fossils: Critters like Tiktaalik (the fish with "wrists") that bridge the gap between water and land.

- Radiometric Dating: Using isotopes like Carbon-14 or Potassium-Argon to get an actual number for the age of a rock.

Common Pitfalls in Fossil Labs

Don't confuse "relative dating" with "absolute dating." Relative dating is just a ranking system—who is older than whom. Absolute dating gives you a birthday. If the question asks how we know a fossil is 250 million years old, "superposition" isn't the answer. You need volcanic ash layers and radioisotopes for that.

💡 You might also like: Fantasy Sex Explained: Why Your Brain Is Your Most Potent Sex Organ

Another thing: Correlation. Geologists use the same fossils found in different parts of the world to "sync up" the timeline. If I find a specific ammonite in Texas and the same one in Morocco, I can conclude those two rock layers were formed at the exact same time. It’s like matching up the page numbers in two different copies of the same book.

The Nuance of "Missing Links"

Scientists actually hate the term "missing link." It implies that evolution is a straight chain. It’s not. It’s a bush. A messy, tangled, overgrown bush. For every species that evolved into something else, there were ten others that hit a dead end and went extinct. When you're filling out your lab, keep in mind that the fossil record is incomplete by nature.

If your worksheet asks why there are gaps, it’s not because the evolution didn't happen. It’s because the conditions for fossilization are incredibly rare. You have to be buried fast. You have to stay buried. The rock has to survive tectonic plate movements. Then, millions of years later, someone actually has to dig you up. The odds are astronomical.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Fossil Record

If you're stuck on a specific question in your lab, stop looking for a 1:1 text match and use these logic gates to find the right answer:

- Check the depth: Is the fossil in a lower layer than the one you're comparing it to? If yes, it’s older. That’s the Law of Superposition.

- Look for "half-life" data: If the question involves math, you’re dealing with absolute dating. Remember that one half-life means 50% of the parent isotope remains. Two half-lives mean 25%.

- Identify the environment: High salt and shells? You’re looking at an ancient seabed. Ferns and coal? That was a swamp.

- Analyze structural changes: If the limbs are getting longer or the teeth are changing shape, describe the environmental pressure. Animals don't change just for fun; they change because their food moved or the climate got colder.

Instead of just hunting for a PDF, use the visual cues in the diagrams. Most fossil record labs use specific "marker" fossils like Brachiopods or Gastropods. If you can identify the shape, you can usually find the era. For example, anything that looks like a giant dragonfly is probably from the Carboniferous period when oxygen levels were high enough to support massive insects.

The fossil record is the only physical diary we have of life on Earth. Treat the lab like a detective case rather than a crossword puzzle. Look for the evidence of change, account for the gaps in the rock layers, and remember that extinction is the rule, not the exception. Most species that have ever lived are gone. We're just looking at the lucky few that left a trace.