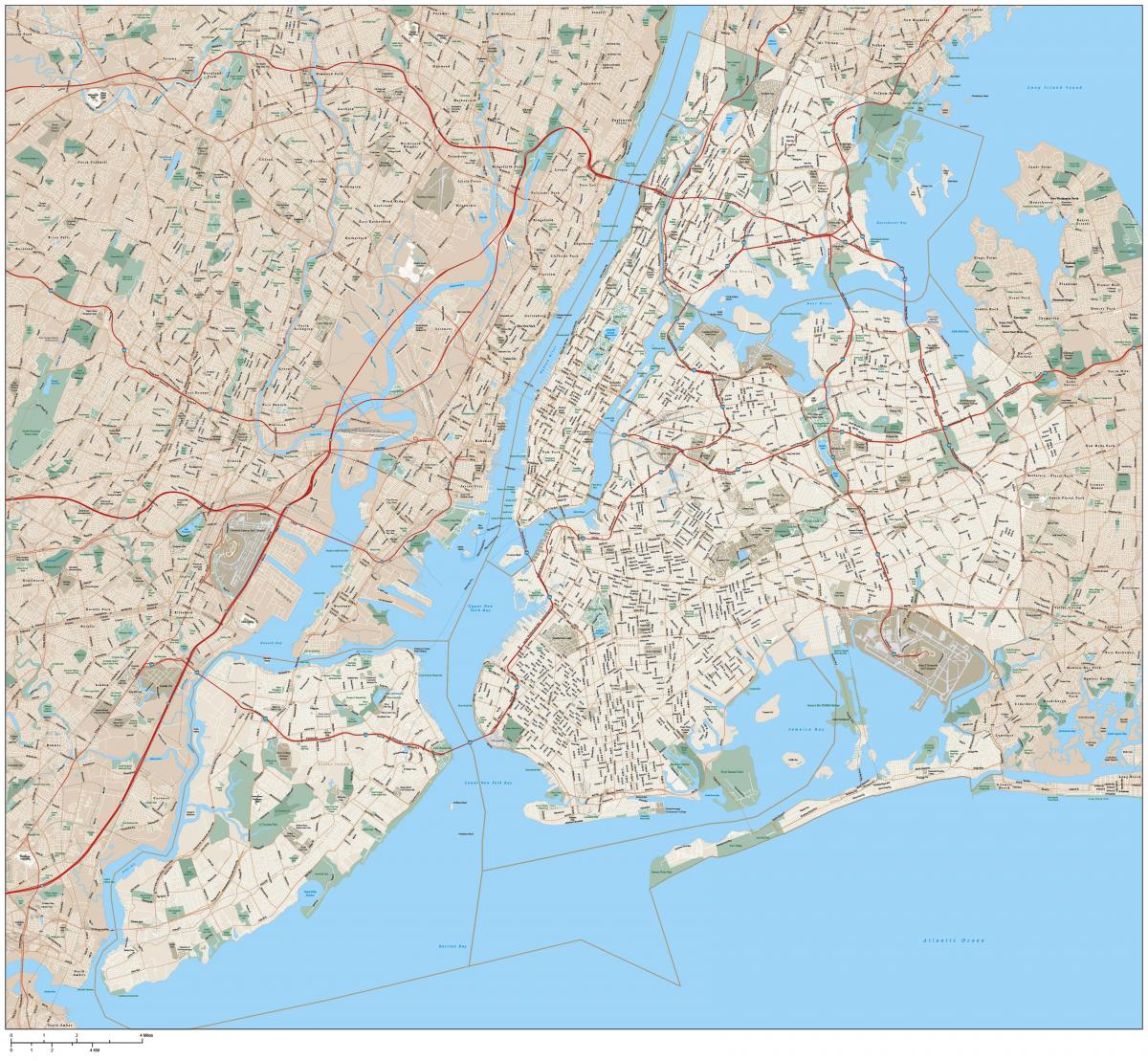

If you’ve ever stood on the corner of Wall Street and Pearl, you’ve probably noticed the air feels a little different than it does in Midtown. It’s cramped. The streets don't make sense. They twist and turn like a pile of dropped spaghetti. Honestly, that’s because you’re walking on a ghost. When you look at a New York City map old versions tell a story that the modern grid system tries its best to hide. It's a messy, fascinating history of Dutch canals, British forts, and a massive 19th-century real estate gamble that literally leveled hills and filled in ponds just to make the city easier to sell.

New York wasn't always a rectangle.

Most people think of the city as a perfect series of numbered blocks. That's the 1811 Commissioners' Plan. But before that, Manhattan was a rugged, hilly island known as Mannahatta, or "island of many hills" in the Lenape language. If you look at the earliest maps, like the famous "Manatus Map" from 1639, the island looks barely recognizable. You won't find Times Square. You won't find Central Park. You’ll just see a few tiny houses at the very southern tip and a whole lot of marshland.

The Dutch Footprint and the Wall That Wasn't a Street

The very first New York City map old enthusiasts usually hunt for is the Castello Plan. Drafted in 1660, it shows New Amsterdam at its peak. It’s surprisingly detailed. You can see individual gardens and the canal that used to run right up Broad Street. Ever wonder why Broad Street is so much wider than its neighbors? It used to be a literal waterway. They filled it in because it was getting gross and smelly, but the width stayed.

Then there’s Wall Street. It’s not just a clever name.

The Dutch actually built a wooden palisade there to keep out the British and the local indigenous populations. If you check the 1660 map, that wall is the northern boundary of the city. Everything north of it was "the wild." It’s wild to think about now, considering Wall Street is basically the center of the financial universe, but back then, it was just the edge of a tiny, muddy outpost.

Why the British Maps Looked So Different

Once the British took over in 1664 and renamed the place New York, the mapping changed. It became more about military control and property lines. The Ratzer Map of 1766 is probably the most beautiful piece of cartography from this era. Bernard Ratzer was a British army officer, and his map is so precise you can see the orchards and the rolling topography of what is now the Lower East Side.

It shows a city that was growing rapidly but still felt like a collection of villages. Greenwich Village was actually a separate village! People used to go there to escape yellow fever outbreaks in "the city" further south. When you look at an old map from the late 1700s, you see these pockets of development connected by "The Post Road."

Everything changed with the hills.

New York used to be incredibly vertical. There was a massive hill called Bayard’s Mount near what is now Grand Street. It was the highest point in Lower Manhattan. The British loved it for the views. But as the city expanded, the planners hated it. They wanted flat ground. So, they basically chopped the top off the hills and shoved the dirt into the ponds. The Collect Pond, which was a massive freshwater source near current-day Foley Square, became so polluted by local tanneries that they just filled it in with the dirt from the leveled hills.

The 1811 Grid: When New York Became a Rectangle

If you’re looking for the moment the modern New York City map old school charm died, it’s 1811. The Commissioners' Plan is the most important document in the city's history. It laid out the grid from 14th Street all the way up to 155th Street.

They didn't care about nature. They didn't care about the existing topography.

📖 Related: Richmond to Puerto Rico: What Most People Get Wrong About This Caribbean Trip

The planners—Simeon De Witt, Gouverneur Morris, and John Rutherfurd—wanted efficiency. They wanted "right-angled houses" because they were cheaper to build and easier to buy and sell. They basically laid a giant cage over the island. If a stream was in the way, they buried it. If a hill was in the way, they dug it up. This is why, if you go to the Upper West Side today, you’ll occasionally see a house that sits at a weird angle or is slightly elevated from the sidewalk. Those are the survivors. They were built before the grid, and the owners refused to move.

The Missing Park

Funny enough, the 1811 map didn't include Central Park. The planners thought the air from the rivers on both sides would be enough for people to breathe. It wasn't until decades later, in the 1850s, that the city realized they had made a mistake and cleared out a massive section of the grid (and destroyed several communities, like Seneca Village) to create the park we know today.

Reading the Subway Maps as History

Not every New York City map old collectors look for is from the 1700s. The evolution of the subway map is a saga all its own. In the early 20th century, there were actually three competing companies: the IRT, the BMT, and the IND. They didn't like each other. They didn't even use the same size tunnels or cars in some cases.

If you look at a 1930s subway map, it’s a chaotic mess of different colors and overlapping lines because each company published its own map. It wasn't until the 1970s that we got the famous Massimo Vignelli map. It was a masterpiece of graphic design—clean, abstract, and colorful.

People hated it.

They hated it because it wasn't geographically accurate. It showed Central Park as a square, which it isn't. It showed the water as beige and the land as gray. New Yorkers got lost. They wanted to know where they were on the ground, not just which line they were on. By 1979, the MTA switched to a more "map-like" map, which is largely what we use today.

How to Find and Use These Maps Today

You don't need to be a billionaire collector to see these. The New York Public Library has one of the best map divisions in the world (the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division). They’ve digitized a massive amount of their collection. You can actually use a tool called the "Chronicle" or the "NYPL Map Warper" to overlay an old map on top of a modern Google Map.

It’s an eerie experience. You can see exactly where a pond used to be while standing in front of a Starbucks.

Practical Tips for Map Hunters

- Look for the "Randel's Farm Maps": Between 1818 and 1820, John Randel Jr. made incredibly detailed maps of the island before the grid was fully built. They show every farmhouse, every tree, and every fence.

- Check the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps: These are from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They were used by insurance companies to see what buildings were made of (to guess how fast they'd burn). They are so detailed they show where the windows were.

- Visit the New York Historical Society: They often have the physical copies on display. Seeing the actual hand-drawn ink on parchment hits differently than a JPEG.

Why the Grid Still Struggles

Even today, the old maps are relevant because the geology of the island doesn't care about the grid. Broadway is the most famous example. It follows an old Wickquasgeck trail that wound its way along the high ground of the island. The 1811 planners couldn't kill it. It was too important. That’s why Broadway cuts diagonally across the city, creating "squares" like Union Square, Madison Square, and Times Square wherever it hits an avenue.

When there’s heavy rain in NYC, the city floods in very specific places. Usually, those places are exactly where the old maps show a stream or a pond. Minetta Lane in Greenwich Village still has a stream running underneath it. Canal Street literally had a canal. We tried to pave over nature, but the old maps keep the receipts.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Old NYC

If you want to actually see this history for yourself, don't just look at a screen. Go to the corner of 14th Street and 4th Avenue. Look at the way the streets don't quite line up. That's the boundary between the old, organic growth of the village and the start of the 1811 grid.

💡 You might also like: Are There Still Bodies on the USS Arizona? The Truth About Pearl Harbor’s Sacred Gravesite

- Download the NYPL Map Warper: Use it on your phone while walking through Lower Manhattan. It’s like X-ray vision for the city.

- Find the "Grid Bolts": Believe it or not, there are still a few original survey bolts from 1811 stuck in the bedrock in Central Park. They were used to mark the intersections of streets that were never built.

- Explore the Financial District: Walk through the narrow alleys like Dutch Street or Coenties Slip. These follow the original 17th-century layout. Feel how the wind tunnels through the narrow gaps compared to the wide avenues uptown.

- Visit the Museum of the City of New York: Their "Mannhattan" exhibit is the gold standard for seeing how the island’s ecology changed over 400 years.

Understanding a New York City map old or new isn't just about getting from point A to point B. It’s about realizing that the city is a living thing, built in layers. Every time you walk over a manhole cover, you might be standing on a spot where a Dutch farmer once planted tulips or where a British soldier stood guard. The grid is just a suggestion; the history is what's actually under your feet.