Montana isn't just one big pile of rocks. People look at a mountain ranges of montana map and see a chaotic jumble of brown and green squiggles, but there’s a very specific rhythm to how this state is built. It’s basically two different worlds split by an invisible line. To the east, you’ve got the vast, rolling plains where the horizon feels like it might actually swallow you whole. To the west? That’s where the earth literally crumpled.

It's massive.

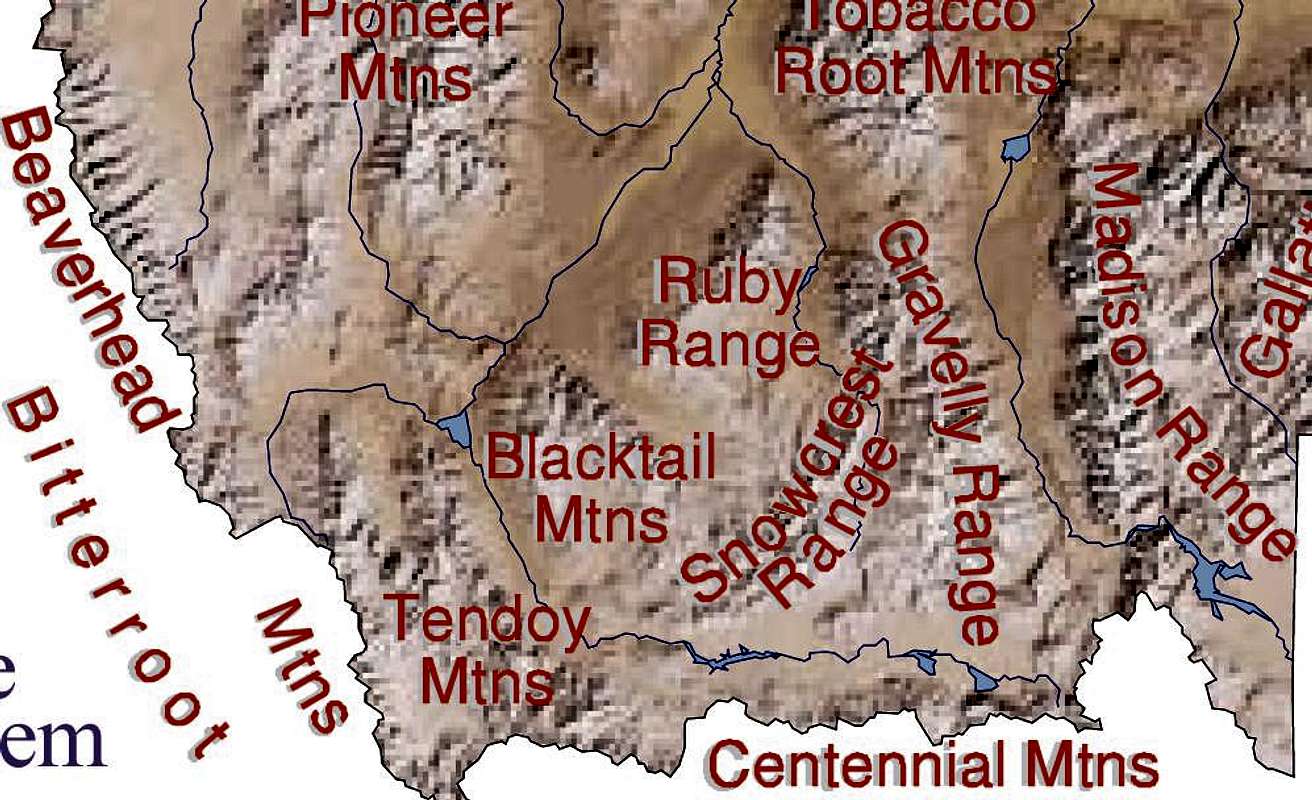

If you’re trying to navigate this place, you have to understand that "The Rockies" is a lazy term. It’s like saying "The Ocean" when you’re actually talking about a specific tide pool in Monterey. Montana holds over 100 named ranges. Some are huge, sprawling complexes like the Absarokas, while others are "island ranges" that just pop up out of the prairie like an afterthought.

The Continental Divide is the Real Boss

When you look at a mountain ranges of montana map, the first thing your eyes should hunt for is the Continental Divide. It’s the jagged spine. This isn't just some geographical trivia; it dictates the weather, the trees, and even how people talk. On the west side, it’s lush. You get that Pacific Northwest moisture that sneaks past Idaho, creating dense forests of cedar and hemlock.

Go east of the Divide? Everything changes.

The air gets crisp and dry. The trees thin out into Douglas fir and ponderosa pine. The mountains themselves look different—sharper, more exposed, and honestly, a bit more intimidating because there’s less greenery to hide the sheer verticality of the rock. Places like the Bitterroot Range on the Idaho border are famous for this. They aren't just hills; they are granite walls that served as a brutal barrier for early explorers. Lewis and Clark nearly lost their entire expedition in the Bitterroots because they underestimated how relentless that terrain is. It’s not a place that cares if you’re prepared.

The Glacier National Park Cluster

Up north, the Livingston and Lewis Ranges dominate the view. This is the Crown of the Continent. If you’ve seen a photo of Montana that made you want to sell your house and move here, it was probably taken in the Lewis Range. These mountains were carved by ice. Big, heavy, slow-moving glaciers ground the limestone and argillite into "horns" and "u-shaped valleys."

💡 You might also like: North Shore Shrimp Trucks: Why Some Are Worth the Hour Drive and Others Aren't

Mount Cleveland is the big dog here, sitting at 10,466 feet.

It’s worth noting that the rocks in Glacier are incredibly old—we’re talking Proterozoic-era sedimentary rock. Because of a geological fluke called the Lewis Overthrust, these ancient rocks were pushed three miles up and 50 miles east, ending up on top of much "younger" rocks. It’s a literal inversion of time.

Those Weird Island Ranges in the East

Most maps focus on the western third of the state because that’s where the high-altitude drama lives. But if you ignore the island ranges, you’re missing the weirdest part of Montana’s soul.

The Big Snowies. The Highwoods. The Crazy Mountains.

These aren't connected to the main Rocky Mountain chain. They’re like geological orphans. The Crazies, in particular, rise out of the plains north of Livingston with a weird, jagged intensity. They look out of place. Local legends and even early settler journals often mention how haunting they look from a distance. Geologically, many of these are laccoliths—igneous intrusions where magma pushed up the surface but didn't quite break through as a volcano. They cooled underground, the softer dirt eroded away, and now you’re left with these isolated fortresses of rock.

The Beartooths and the Highest Ground

South of Billings, things get serious. This is where the mountain ranges of montana map hits its highest notes. The Beartooth Range is home to Granite Peak, the highest point in the state at 12,807 feet.

📖 Related: Minneapolis Institute of Art: What Most People Get Wrong

This isn't just a mountain range; it’s a high-altitude plateau.

Driving the Beartooth Highway is basically like taking a trip to the Arctic Circle without leaving your Subaru. You’re above the tree line for huge stretches. Even in July, you’ll see snow. The rocks here are some of the oldest on the planet—precambrian crystalline rock that’s roughly four billion years old. To put that in perspective, the Earth itself is only about 4.5 billion years old. You are literally walking on the foundation of the world.

Why the Map Can Be Deceptive

If you're looking at a map to plan a hike or a hunt, be careful.

A "range" in Montana can be a 100-mile long behemoth or a 10-mile long ridge. The Cabinet Mountains in the far northwest are a great example of a "small" footprint with massive impact. They are rugged, wet, and famously inhabited by grizzly bears. Then you have the Gallatin Range, which runs from Bozeman straight down into Yellowstone. The Gallatins are weird because they contain a petrified forest. Thousands of years ago, volcanic mudflows (lahars) buried standing trees, turning them to stone. You won't see that on a standard topographic map, but it’s there.

- Western Ranges: Deep valleys, heavy timber, high precipitation.

- Central Ranges: High alpine basins, limestone cliffs, "Blue Ribbon" trout streams in the valleys.

- Island Ranges: Isolated, wind-blasted, rising directly from the grass.

The Bitterroot Valley Split

The Bitterroots are a favorite for a reason. They represent a massive granite batholith. On the other side of the valley, you have the Sapphires. It’s a total contrast. The Bitterroots are steep, rocky, and dramatic. The Sapphires? Much more rounded and accessible. If you’re looking at a mountain ranges of montana map for recreation, the Bitterroots are for the hardcore climbers, while the Sapphires are where you go for a long, meandering trail run or to look for, well, sapphires.

Survival and Navigation Realities

Don't trust your phone's GPS blindly in these ranges.

👉 See also: Michigan and Wacker Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong

The geography of Montana is notorious for "signal shadows." You can be on a ridge with five bars of service and drop 200 feet into a drainage where you won't get a signal for three days. Expert hikers in the Mission Mountains—which are some of the most spectacular, jagged peaks in the lower 48—always carry paper maps. The Missions are part of the Flathead Indian Reservation, and they require a special permit to hike. It’s a managed wilderness, and the peaks there, like McDonald Peak, stay snow-capped long after the valleys have turned to dust.

Misconceptions about the "Big Sky"

People think "Big Sky" refers to the whole state. It actually started as a marketing slogan for the ski resort in the Madison Range. But the name stuck because when you're in the middle of these ranges, the sky really does feel larger. The elevation change from the valley floors (around 3,000-4,000 feet) to the peaks (10,000+ feet) creates a massive vertical relief that makes the atmosphere feel thinner and the light look sharper.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you are actually planning to visit or study these areas, start by layering your maps. Don't just look at a road map. Look at a shaded relief map alongside a National Forest map.

- Identify the drainage: Every mountain range in Montana is defined by the river that drains it. The Madison, the Gallatin, the Yellowstone, the Bitterroot. If you know the river, you know the range.

- Check the rock type: If you're in limestone (like the Bob Marshall Wilderness), expect caves and dramatic cliffs. If you're in granite (like the Beartooths), expect boulder fields and alpine lakes.

- Respect the weather: Montana mountain ranges create their own weather systems. A sunny day in Great Falls can be a blizzard in the Little Belts within two hours.

The mountain ranges of montana map is a living document. Trails change, glaciers shrink, and fires reshape the forests every summer. But the rock remains. Whether it’s the volcanic leftovers of the Absarokas or the ancient thrust-faults of the Lewis Range, this state is a masterclass in how the earth can be folded, broken, and beautiful all at once.

Practical Next Steps:

Download the Avenza Maps app and grab the specific USFS (United States Forest Service) quads for the range you're targeting. These maps show the logging roads and trailheads that Google Maps often ignores. If you're heading into the backcountry, check the MT Avalanche Center reports, even in late spring, as the high-altitude snowpack in ranges like the Bridgers or Madisons stays active and dangerous long after the "ski season" officially ends.