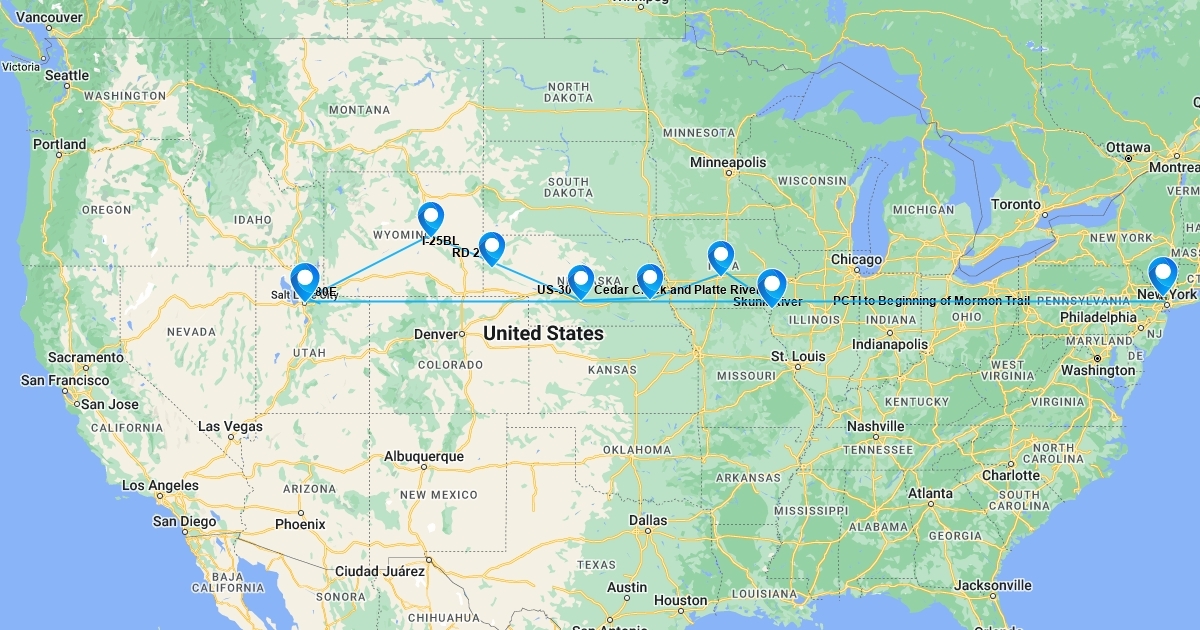

You’ve probably seen the classic dashed line on a classroom wall or a grainy textbook page. It looks simple. One long, straight-ish shot from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Salt Lake Valley. But if you actually look at a detailed map of Mormon pioneer trail history, you realize that line is a bit of a lie. It wasn't one path. It was a shifting, muddy, terrifyingly complex network of tracks that evolved every single year between 1846 and 1869.

The trail is roughly 1,300 miles long.

That’s a lot of dirt. Honestly, when people look for a map today, they’re usually trying to find out where their ancestors got stuck in the mud or where they can take their SUV for a weekend history trip. But a static map doesn't tell you about the "Sugar Creek" disaster or the way the trail actually split into dozens of braids depending on which river was flooding that week.

Why the Map of Mormon Pioneer Trail Changed Every Year

Early travelers didn't have a Google Maps route. They had "The Latter-day Saints' Emigrants' Guide," published by William Clayton in 1848. Clayton was a bit of a nerd—in a good way. He obsessed over distances. He actually helped invent a version of the odometer (the "roadometer") because he was tired of guessing how far they’d walked. His guide was the first real attempt to turn a chaotic trek into a repeatable map.

But here is the thing: the trail in 1846 looked nothing like the trail in 1850.

In the beginning, the pioneers were basically fleeing for their lives. They left Nauvoo in February. That was a massive mistake, geographically speaking. If you look at a map of that first stretch across Iowa, it’s a zig-zag of misery. They weren't following an established road; they were making one through knee-deep sludge. It took them 131 days just to cross Iowa. Later, with a better map and established waystations like Garden Grove and Mount Pisgah, that same stretch took only a few weeks.

The Missouri River Bottleneck

Once you hit the Missouri River, the map gets messy. This is where "Winter Quarters" (modern-day Omaha/Florence, Nebraska) comes in. If you’re looking at a map of Mormon pioneer trail sites, this is a massive hub. Thousands lived in sod huts and dugouts here. Many didn't make it out. The trail from here followed the north side of the Platte River. Why the north side? Because the Oregon Trail and the California Trail travelers usually stuck to the south side. The Mormon pioneers wanted to avoid conflict. They wanted their own space.

Basically, they traded better terrain for a bit of peace and quiet.

💡 You might also like: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

Key Landmarks You’ll Find on a Modern Map

If you’re driving the route today, you aren't looking for ruts in the grass—though you can still find them if you know where to peek. You’re looking for the big geological markers.

Chimney Rock is the big one. It’s in western Nebraska. For pioneers, this was the psychological halfway point. If you see it on a map today, it looks like a tiny needle. Back then, it was a lighthouse. It meant you were leaving the flat prairies and hitting the "High Plains."

Then there's Scott’s Bluff.

And Fort Laramie.

By the time the trail hits Wyoming, the map starts to climb. You’ve got South Pass. This is a crucial piece of geography. It’s a wide, gentle gap in the Rocky Mountains. If it weren't for this specific gap, the wagon trains probably wouldn't have made it to the Great Basin at all. It’s the highest point on the trail, about 7,412 feet up.

The Sweetwater River Loop

The trail follows the Sweetwater River back and forth. You cross it over and over. If you look at a topographical map, you’ll see Independence Rock. People called it the "Great Register of the Desert." Thousands of people carved their names into the stone. It’s still there. You can go touch the names today. It’s a weird, visceral connection to a map that’s over 170 years old.

The Handcart Routes: A Darker Version of the Map

We have to talk about 1856.

📖 Related: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

Most people think of covered wagons. But for a few years, because wagons were expensive, people literally pushed handcarts. If you look at the map of Mormon pioneer trail movements for the Willie and Martin handcart companies, it’s a map of a tragedy. They started too late in the year.

By the time they hit Martin’s Cove and Rocky Ridge in Wyoming, the snow had started.

These aren't just points on a map; they are burial grounds. The geography here is brutal. High altitude, no cover, and screaming winds. When you look at these specific locations on a map today, you notice how far they are from any major towns. Even in 2026, these spots feel isolated. Back then? They were the end of the world.

How to Use a Map of Mormon Pioneer Trail for Travel Today

If you want to actually follow this, don't just use a generic paper map.

- Start at the Nauvoo Temple. The trail literally starts at the foot of the hill.

- Follow Highway 2 in Iowa. This roughly parallels the original 1846 route.

- Visit the Mormon Trail Center at Historic Winter Quarters. They have some of the best physical maps and dioramas that explain the river crossings.

- Use the National Park Service (NPS) Auto Tour Route. The NPS manages the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail. They’ve marked the roads with a specific logo—a silhouette of a wagon.

You should also check out the Church History sites. They’ve preserved chunks of the trail where you can still see "swales." Those are the deep depressions in the earth left by thousands of iron-rimmed wheels.

Common Misconceptions About the Trail’s Path

A lot of people think the trail ended at the Salt Lake Temple. Technically, the "destination" was the valley, but the trail kept moving. Once they arrived at Ensign Peak, they started mapping out the rest of the West. The Mormon Trail was really just the beginning of a much larger map that stretched down into Arizona and up into Idaho.

Also, it wasn't a race.

👉 See also: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

People think of it as one big sprint. It was more like a conveyor belt. There were people going west and people going back east to help others. The map was a two-way street.

Technical Reality: Mapping the Ruts

In the last few years, archaeologists have started using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). This is basically a laser that "sees" through grass and brush. It has revealed sections of the trail that we thought were lost to time or farming.

We’re discovering that the "official" maps were sometimes off by a mile or two.

Why does that matter? It matters because it tells us where people actually camped. It shows us where they diverted to find water during droughts. It turns the map of Mormon pioneer trail into a living document rather than a dead line on a page.

Putting the Map Into Perspective

Walking 15 miles a day is hard. Doing it while pulling a 300-pound cart is insane. Doing it while burying your children is something else entirely.

When you look at the map, try to see the elevation gains. Look at the "Devil’s Gate." Look at the crossing of the Green River. These weren't just names; they were obstacles that broke people. The map is a record of endurance.

If you're planning a trip to see these sites, you'll want to focus on the Wyoming stretch. That’s where the trail is most "pure." In Illinois and Iowa, most of it has been paved over by cornfields and suburbs. But in Wyoming? You can stand on a ridge, look at a map, and see exactly what Brigham Young or Eliza R. Snow saw.

It’s big. It’s empty. And it’s still there.

Actionable Next Steps for Trail Explorers

- Download the NPS App: Look for the "National Park Service" app and search for the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail. It has GPS-linked points of interest that tell you exactly what happened where you are standing.

- Check the Weather: If you are visiting the Wyoming sections (South Pass or Martin’s Cove), do not go in the winter without serious prep. The map might look like a simple road, but the wind can be lethal even today.

- Visit Local Museums: Small-town museums in places like Casper, Wyoming, or Council Bluffs, Iowa, often have "oversized" local maps that show the trail crossing individual modern-day farms.

- Support Preservation: Organizations like the Oregon-California Trails Association (OCTA) work to keep these ruts from being bulldozed. They offer detailed trekking maps for serious hikers.

The trail isn't just a history lesson. It's a physical scar on the American landscape. Seeing it on a screen is fine, but standing in a wagon rut that’s two feet deep? That’s how you actually understand the map.