You’ve probably seen the posters. Huge, sweeping shots of the Varanasi ghats at sunset, orange light hitting the water, and thousands of people gathered for the Aarti. It’s iconic. But if you actually look at the Ganga river in India map, the story gets way more complicated than just a few holy cities. It is a massive, sprawling 2,525-kilometer journey that basically keeps North India alive. Honestly, calling it just a "river" feels like an understatement. It’s a literal lifeline for over 400 million people. That's more than the entire population of the United States, all relying on one single basin.

Maps are kinda funny because they make things look static. You see a blue line snaking across the Indo-Gangetic Plain and think, "Okay, there it is." But the Ganga is a shapeshifter. It starts as a freezing glacial stream in the Himalayas and ends as the world’s largest delta in the Bay of Bengal.

Where the Blue Line Actually Begins

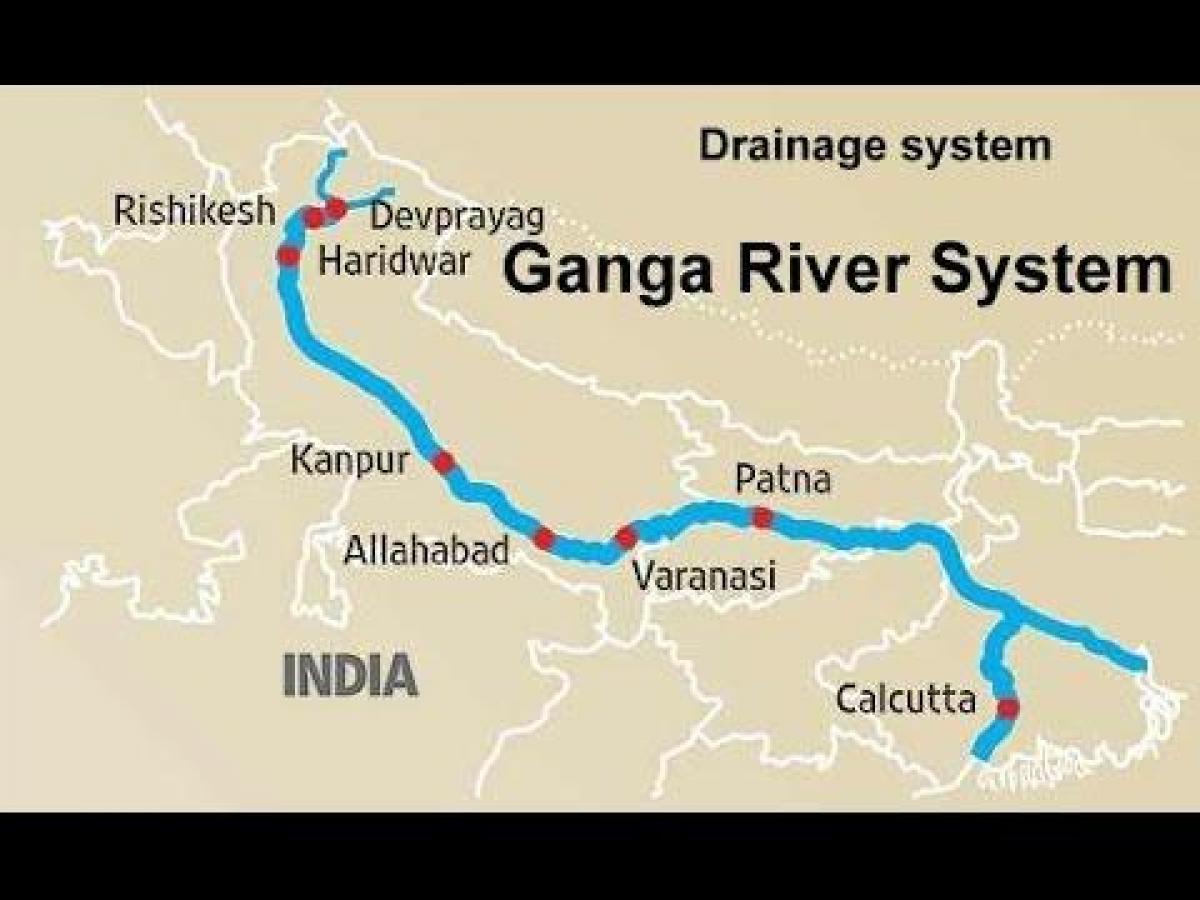

If you’re looking at the top of the Ganga river in India map, your eyes will land on Uttarakhand. Most people think the Ganga just "appears" at Gangotri. Not quite. The river officially becomes the "Ganga" only after two distinct rivers—the Alaknanda and the Bhagirathi—slam into each other at a place called Devprayag. Before that point, it’s just a series of turbulent mountain tributaries.

The Bhagirathi is technically the source stream, coming out of the Gaumukh ice cave at the base of the Gangotri Glacier. It’s brutal terrain. If you ever go there, you’ll notice the water isn't that classic muddy brown you see in the plains; it’s a piercing, translucent turquoise-grey. It’s fast. It’s loud. It’s nothing like the slow-moving giant it becomes later on.

The Great Turn: Why the Map Curves

Once the river hits the plains at Rishikesh and Haridwar, the map changes. The descent is over. Now, the Ganga starts its long, eastward crawl across the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal.

One thing most people get wrong about the Ganga’s path is its relationship with the Yamuna. On any decent Ganga river in India map, you’ll see the Yamuna running almost parallel to the west before they finally meet at Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad). This spot, the Sangam, is arguably the most important geographical point in Hindu theology. It’s where the "visible" rivers meet the "invisible" Saraswati. Geography and mythology just sort of blur into one here.

The Middle Basin Realities

As it flows through Kanpur and Varanasi, the river slows down significantly. This is where the sediment kicks in. The Ganga carries a massive amount of silt—the stuff that makes the North Indian plains some of the most fertile land on the planet. But there’s a downside. All that silt causes the river to change its course frequently.

If you look at old colonial-era maps versus a modern satellite view, the riverbanks have shifted by kilometers in some places. It’s a "braided" river. It splits, forms islands, and rejoins. This makes farming near the banks a high-stakes gamble. One year you have a lush field; the next, your land is at the bottom of the riverbed.

The Delta: Where the Map Gets Messy

By the time the river reaches West Bengal, it stops being a single line. It splits. The Hooghly River heads south towards Kolkata, while the main branch, the Padma, enters Bangladesh.

This is the Sunderbans. It’s a maze. If you’re looking at this section of the Ganga river in India map, it looks like someone spilled blue ink across the coast. It is the largest mangrove forest in the world. It’s also home to the Royal Bengal Tiger, which, interestingly, has adapted to swimming in the salty, tidal waters of the delta.

The scale of the delta is hard to wrap your head around. It covers about 100,000 square kilometers. It’s a place of constant flux where the distinction between "land" and "water" is basically a suggestion. Cyclones frequently reshape the coastline here, proving that the map is really just a snapshot of a moment in time.

Why the Map is Changing Right Now

We have to talk about the crisis. If you look at the Ganga today versus thirty years ago, the volume of water is different. Climate change is hitting the Gangotri glacier hard. According to the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, the glacier has been retreating at a rate of about 22 meters per year.

🔗 Read more: Shedd Aquarium: Why It Is Still Chicago’s Best Kept Secret (Sorta)

Less ice at the source means less water in the dry season. Then there are the dams. The Tehri Dam, one of the tallest in the world, literally holds back the Bhagirathi. While these projects provide much-needed electricity, they also change the "pulse" of the river.

Pollution is the other elephant in the room. The National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG), also known as Namami Gange, has spent billions trying to fix the sewage issues in cities like Kanpur, which is famous for its leather tanneries. While the water quality has improved in certain stretches, the sheer volume of waste from a population of 400 million is a Herculean challenge to manage.

Mapping the Spiritual Landscape

You can’t understand the Ganga river in India map without looking at the "Tirthas" or pilgrimage sites. The river is a goddess (Ganga Ma). For millions, the map isn't about GPS coordinates; it’s about the spots where the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds is thin.

- Gangotri: The physical and spiritual origin.

- Haridwar: Where the river leaves the mountains.

- Prayagraj: The great confluence.

- Varanasi: The city of light, where dying on the banks of the river is believed to grant Moksha (liberation).

Practical Tips for the Modern Traveler

If you’re planning to follow the river’s path, don't just stick to the famous spots.

💡 You might also like: Nampa Idaho Weather 7 Day Forecast: Why the Inversion Is Messing With Your Plans

- Check the Season: Do not go during the Monsoon (July-September). The Ganga is terrifying when it’s in spate. It’s not a peaceful river; it’s a brown, churning wall of water that swallows temples.

- Use Digital Maps Wisely: In places like Varanasi, Google Maps will fail you in the narrow alleys (galis). Use the river as your North Star. If you’re walking toward the water, you’re heading toward the Ghats.

- The Train Route: The rail line from Delhi to Patna often runs parallel to the river. It’s one of the best ways to see the sheer scale of the floodplains without the stress of driving.

- Boat Rides: Always negotiate. In Varanasi or Rishikesh, a boat ride at dawn is non-negotiable, but the first price is never the real price.

Understanding the "Self-Purifying" Mystery

There’s this long-standing claim that Ganga water doesn't go bad. People keep it in copper pots for years. Scientists have actually looked into this. There’s a high concentration of "bacteriophages" in the water—viruses that literally eat bacteria.

There's also a high dissolved oxygen content due to the river's turbulent descent from the Himalayas. However, don't take this as a green light to drink it straight in the plains. The "healing" properties of the water are real at a microbiological level, but they are currently being overwhelmed by industrial chemicals and untreated sewage in the mid-stream sections.

Actionable Insights for Exploration

If you really want to understand the Ganga, you need to see it at two different points. See it in the mountains, and see it in the plains. The contrast is what makes the river what it is.

Start by downloading a high-resolution topographical map of Uttarakhand to see the "Panch Prayag"—the five confluences where various rivers merge to eventually form the Ganga. This gives you a much better appreciation for the hydrology than a simple road map ever could.

For those interested in the environmental side, check the real-time water quality dashboards provided by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) of India. They track the "BOD" (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) levels at various points along the river. It’s a sobering but necessary look at the reality behind the sacred imagery.

The Ganga isn't just a line on a map. It’s a living, breathing, and unfortunately, struggling organism. Whether you see it as a goddess, a water source, or a geographical marvel, understanding its path is the first step to understanding India itself.

To truly map the Ganga, look beyond the ink. Observe the seasonal shifts in the floodplains of Bihar and the way the river expands to several kilometers wide during the rains. Study the path of the National Waterway 1, which aims to use the Ganga for large-scale cargo shipping between Haldia and Prayagraj. By looking at these logistical and environmental layers, the Ganga river in India map stops being a static image and becomes a window into the future of the subcontinent.