You’re looking at an Erie Canal map and probably thinking it’s just a straight shot across New York. It isn't. Not even close. If you tried to navigate the original 1825 route using a modern GPS, you’d end up driving through a Wegmans parking lot or hitting a dead end in a swampy field near Rome.

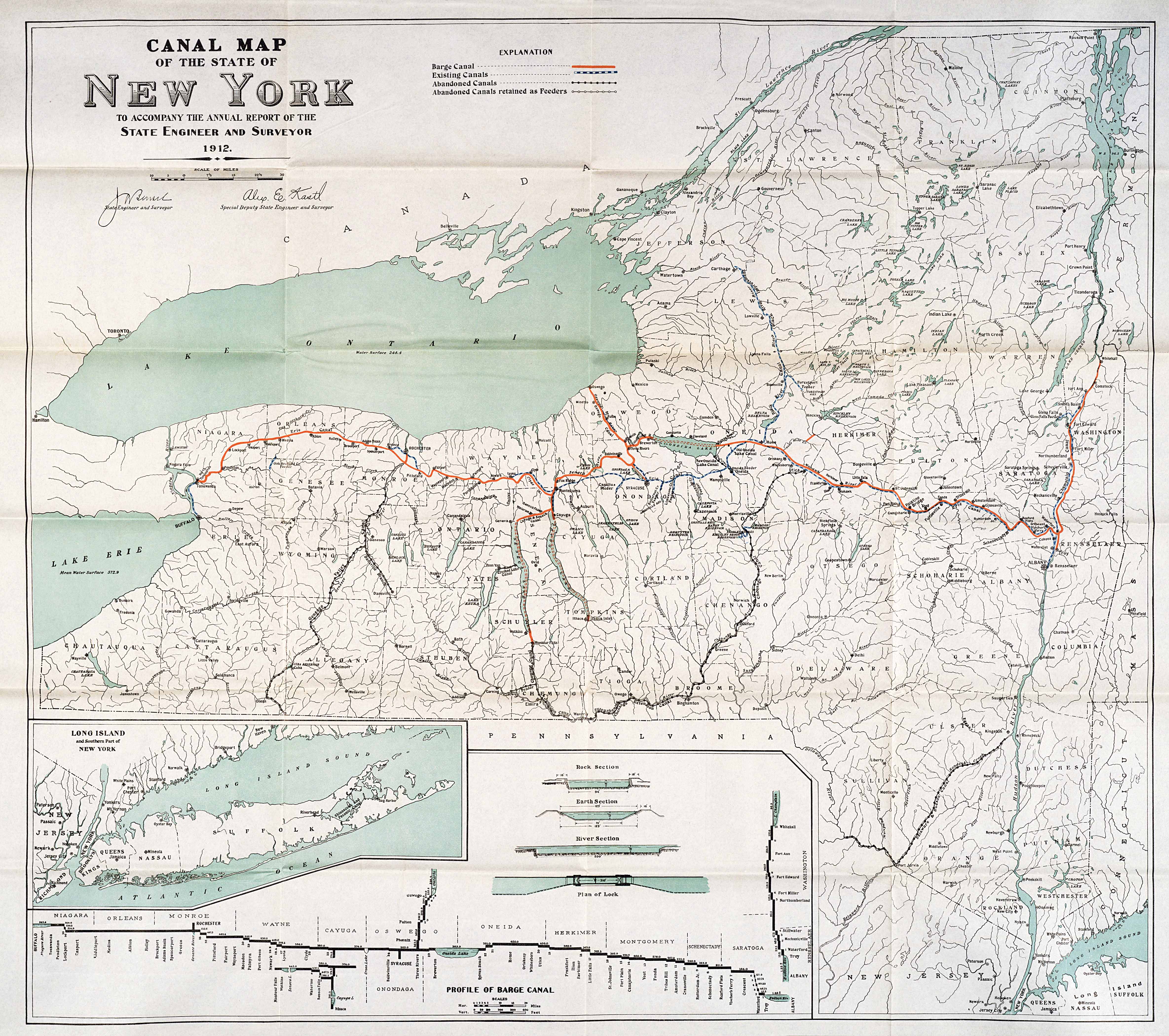

The "Clinton’s Ditch" people talk about in history books has been moved, widened, and basically rebuilt three times. What we call the Erie Canal today is actually the "Barge Canal," a massive engineering project from the early 1900s that abandoned huge chunks of the original path. Honestly, seeing where the old water used to flow versus where the boats go now is the only way to actually understand how New York became an economic powerhouse.

Reading the Erie Canal Map: The Three Different Versions

Most people don't realize there are actually three distinct versions of this waterway. First, you have the Original Erie Canal (1825). It was tiny. Only four feet deep and 40 feet wide. It was basically a liquid highway for mules pulling boats. Then came the Enlarged Erie (1836–1862) because the first one was so successful it literally clogged with traffic. Finally, we have the Barge Canal (1918–present), which is what you see on most modern Google Maps.

The map changed because the technology changed. Early engineers avoided rivers. They hated them. Rivers had floods and droughts and unpredictable currents. So, the original map shows a "land cut" canal that runs alongside rivers like the Mohawk but never actually enters them. By 1918, we had powerful enough engines to handle the river currents, so the map shifted. We "canalized" the rivers. If you look at a map of the Mohawk Valley today, the canal and the river are often the same thing, but in 1825, they were strictly separate entities.

The Western Section: Buffalo to Rochester

This is the part that feels the most like the old days. From Buffalo, the canal heads east, cutting through the Niagara Escarpment at Lockport. This is the "Deep Cut." It was a nightmare to build. You can still see the "Flight of Five" locks here. On a map, this looks like a jagged staircase. It’s one of the few places where the Erie Canal map hasn't shifted significantly because, frankly, there was no better way through the rock.

Once you pass Lockport, the canal stays high. It follows the 60-mile level, which is exactly what it sounds like: a long stretch of water with no locks. It’s weirdly peaceful. In Rochester, the map gets messy. The original canal used to go right through the center of the city, crossing over the Genesee River on a massive stone aqueduct. Today, that aqueduct is a bridge for Broad Street, and the canal loops around the south side of the city. If you’re looking at a map and wondering why there’s a random dry stone bridge in downtown Rochester, that’s why.

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

Why the "Clinton’s Ditch" Route Disappeared

DeWitt Clinton was mocked for this project. They called it a "folly." But it worked. The reason so much of the original Erie Canal map is gone is purely practical. When the canal was enlarged, they didn't just dig deeper; they often moved the whole thing a few hundred yards to straighten out curves.

Take the town of Jordan or Camillus. In these spots, the modern canal is miles away to the north. The old canal bed is now a "feeder" or just a linear park. If you follow the Empire State Trail, you're often biking on the towpath where the mules used to walk. It’s a strange feeling. You’re on the map, but the water is gone. You’ll see ruins of stone locks sitting in the middle of the woods, looking like Mayan temples in the New York brush.

The Middle Section and the Great Swamp

Crossing the middle of the state was the hardest part for the mappers. The Montezuma Marsh was a graveyard. Thousands of workers died of malaria here because they were digging through muck. If you look at a 19th-century Erie Canal map, the line through Montezuma is thin and precarious. Today, the canal uses the Seneca River. It’s wider, deeper, and much more forgiving for the big yachts and tugs that traverse it now.

One detail most people miss? The Schoharie Crossing. It’s near Fort Hunter. Here, the canal had to cross the Schoharie Creek. They built a massive aqueduct, but the creek was so violent it kept knocking it down. Today, you can see the arches of the "Empire State’s Stonehenge" standing in the water. It’s a visual reminder that the map was constantly being rewritten by nature.

How to Use an Erie Canal Map for Modern Travel

If you’re planning a trip, don't just rely on a standard road map. You need a specialized canal chart. The New York State Canal Corporation issues these, and they are vital for understanding bridge clearances and lock locations.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

- Lock Frequency: Between Albany and Buffalo, there are 35 locks. They are numbered 2 through 35 (there is no Lock 1).

- The Elevation Change: You are climbing. From the Hudson River to Lake Erie, the water rises about 565 feet. It’s like taking a boat up a 50-story building.

- The "Blue Line": In legal terms, the "Blue Line" on old maps represents the state-owned boundary of the canal. Property owners along the canal still deal with this today.

The Ghost Map: Finding the Abandoned Sections

For the real nerds, the fun is in the ghost map. This involves overlaying 1850 maps with 2026 satellite imagery. You can find the "Long Level" near Utica where the canal was filled in to make way for Oriskany Boulevard. In Syracuse, the canal ran right down Erie Boulevard. That’s why the street is so wide and flat. You are literally driving where boats used to float.

It’s kind of wild to think about. A massive piece of infrastructure that dictated where every major city in New York was built—Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Utica—is now mostly hidden in plain sight.

Nuance and Controversy: It Wasn't All Progress

We shouldn't pretend the map was a gift to everyone. The construction of the canal forcibly displaced Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) communities. The map was drawn over their ancestral lands without their consent. When you look at the Erie Canal map, you're looking at a map of Western expansion that came at a very high cost to the people who were already there. Historians like Peter Lord have documented how the canal’s path was chosen to maximize land speculation for wealthy New Yorkers, often bypassing established settlements that didn't pay up.

Also, the map is still changing. Climate change is a factor now. Increased flooding in the Mohawk Valley means the Canal Corporation has to manage water levels more aggressively than they did 100 years ago. The map isn't a static document; it’s a living management plan.

Navigating the Canal Today: Practical Steps

If you want to actually see this for yourself, don't just stay on the Thruway (I-90). The Thruway was built to follow the canal’s path, but it stays far enough away that you miss the details.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

1. Get the Right Maps

Don't use Apple Maps for the water. Download the "Cruising Guide to the New York State Canals." It has the nautical details you need, like the location of "wall space" for free overnight docking. Many canal towns like Fairport or Brockport offer free power and water to boaters to encourage tourism.

2. Visit the Parks, Not Just the Locks

Places like Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site or the Camillus Erie Canal Park allow you to see the "Original," "Enlarged," and "Modern" canals all in one spot. It’s the only way to wrap your head around the scale.

3. Check the Bridge Clearances

If you’re on the water, the Erie Canal map tells you one crucial thing: how high your boat can be. In the western section, some bridges are as low as 15.5 feet. If you’ve got a big flybridge on your yacht, you aren't making it to Buffalo. You’ll have to turn around or take the mast down.

4. Follow the Empire State Trail

For those on land, the 750-mile Empire State Trail follows the canal route from Albany to Buffalo. It’s mostly flat (obviously, because water doesn't go uphill without locks) and provides the best view of the remaining 19th-century stonework.

The Erie Canal isn't a museum piece. It’s still a functioning industrial and recreational corridor. It’s a weird mix of 200-year-old stone and modern hydraulic steel. Whether you're kayaking a small stretch near Pittsford or taking a week-long cruise from the Hudson to the Great Lakes, the map is your guide to one of the greatest engineering feats in human history. Just remember that the line on the paper represents a lot of sweat, a lot of change, and a whole lot of mud.

Next Steps for Your Trip:

Download the official New York State Canal Corporation navigation charts to identify "Low Bridge" areas and Lock contact frequencies (VHF Channel 13). If you are traveling by land, use the Empire State Trail interactive map to find trailhead parking near historic aqueduct ruins in Palmyra and Nine Mile Creek. These locations offer the most intact examples of the 19th-century masonry mentioned above. Management of the canal is currently overseen by the New York Power Authority; check their "Notice to Mariners" for any seasonal closures or depth restrictions before heading out.