Maps lie. Well, maybe they don't lie on purpose, but looking at an arctic national wildlife refuge alaska map on a glowing smartphone screen gives you a false sense of security that can get you killed. Or, at the very least, leave you staring at a vast expanse of nothingness wondering where the "trail" went.

There are no trails.

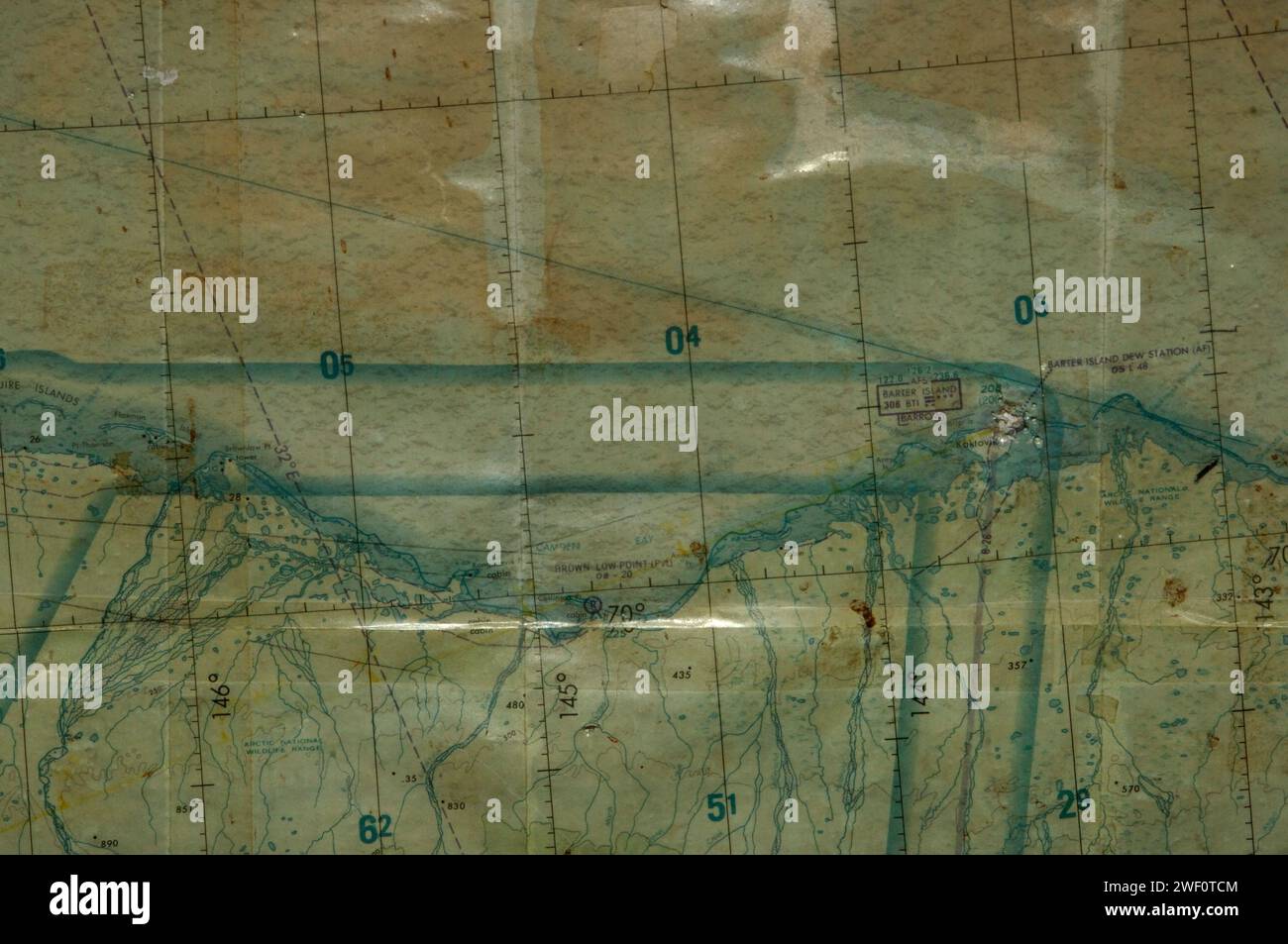

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is about 19.3 million acres. To put that in perspective, that’s roughly the size of South Carolina, but without the paved roads, gas stations, or friendly Waffle Houses. When you unfold a physical map of this region, you aren't looking for the nearest visitor center. You're looking for survival. Most people think of Alaska as "wild," but ANWR is the PhD level of wilderness. It's the "Coastal Plain," the "Brooks Range," and the "Ivishak River" all bleeding into one another in a way that defies a simple GPS coordinate.

Navigation in the Land of No Landmarks

If you’re staring at an arctic national wildlife refuge alaska map, you’ll notice a distinct lack of lines. Most maps are defined by where humans have built things. Here, the lines are dictated by the Porcupine Caribou Herd or the shifting gravel bars of the Canning River.

Honestly, the map is just a suggestion of where the mountains might be.

Because of the scale, 1:250,000 scale USGS maps are common, but they are kiddy pools compared to the reality of the 1:63,360 scale (inch-to-a-mile) maps you actually need if you’re trekking. Even then, the permafrost melts and shifts. A pond on your map from 1980 might be a meadow today. A river channel might have moved half a mile to the west after a particularly brutal spring breakup.

You’ve got to understand the "1002 Area." On the map, it’s a specific slice of the coastal plain—about 1.5 million acres—that has been the center of political tug-of-wars for decades. From a cartographic standpoint, it looks like a flat shelf between the mountains and the Beaufort Sea. In reality, it’s a chaotic mosaic of tussocks. Tussocks are these basketball-sized clumps of sedge grass that wobble when you step on them. Walking three miles on the 1002 Area is like walking fifteen miles on a treadmill while someone throws rocks at your shins.

The Scale of the Brooks Range

The Brooks Range cuts across the refuge like a jagged spine. On a map, the mountains look like little brown shaded bumps. When you’re standing at the base of the Romanzof Mountains, you realize those "bumps" are nearly 9,000 feet of vertical rock and ice. Mount Isto and Mount Chamberlin are the big ones.

For years, there was a debate about which was taller. Maps were updated as recently as 2014 using new laser technology (LiDAR) to prove that Mount Isto is actually the highest peak in the US Arctic. This wasn't just for bragging rights; it matters for bush pilots who are trying to clear ridges in heavy fog with maybe twenty feet of visibility.

📖 Related: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

Bush pilots are the heartbeat of ANWR. You don't drive here. There is no road. The Dalton Highway (the "Haul Road") skirts the western edge, but to actually get into the refuge, you’re flying out of Fairbanks or Fort Yukon and landing on a gravel bar. If your arctic national wildlife refuge alaska map doesn't show the airstrips, it’s because "airstrip" is a generous term for "a patch of rocks that won't flip a Piper Super Cub."

The Ghost of the Canning River

The western boundary of the refuge is largely defined by the Canning River. Rivers in the Arctic are weird. They don't just flow; they braided.

Think of a braid as a giant, liquid knot.

One year, the main channel is on the east side; the next year, it’s on the west. If you’re using an old map to plan a float trip, you might find yourself dragging a heavy raft over dry rocks because the river decided to move. Local guides like those from Arctic Wild or Wilderness Birding Adventures spend half their time "reading" the water because the paper map is already obsolete by the time the ink dries.

Then there’s the issue of magnetic declination.

Because you’re so far north, your compass needle wants to point somewhere toward the Hudson Bay rather than true north. In the refuge, the declination can be 20 degrees or more. If you forget to adjust your compass to match your arctic national wildlife refuge alaska map, you’ll end up in Canada when you meant to go to the coast. It’s a rookie mistake that happens more than people like to admit.

Wildlife doesn't follow the lines

Maps usually show "habitats." You’ll see a green shade for forest and a tan shade for tundra.

The Porcupine Caribou Herd doesn't care about your shading.

👉 See also: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

They migrate hundreds of miles from the Yukon into the refuge to have their calves on the Coastal Plain. This isn't just a fun fact; it’s the reason the refuge exists. If you’re looking at a map to plan a photography trip, you’re looking for the intersection of the foothills and the plain. This is where the insects are slightly less murderous because of the breeze, and the caribou congregate.

Wait, did I mention the mosquitoes?

No map can capture the density of the bugs. They are a physical presence. They show up on radar sometimes. You can be the best navigator in the world, but if you’re being eaten alive by a cloud of black flies, you’re going to make a mistake reading your coordinates.

The Digital vs. Analog Debate

Kinda feels like we should rely on Gaia GPS or OnX nowadays, right?

Sure, until your battery dies because the temperature dropped to 30 degrees in the middle of July. Lithium batteries hate the Arctic. The cold sucks the life out of them. Also, the satellite coverage can be spotty when you’re tucked into a deep valley in the Brooks Range.

Always carry the paper map. Always.

Put it in a waterproof case. Not a "water-resistant" one. A heavy-duty, submersible sleeve. If you drop your map in the Hulahula River and it turns into paper mache, you are effectively blind. You’ll be looking at a landscape that has no trees to climb for a better view and no landmarks other than the sun, which, in the summer, just circles around the sky without setting, making "West" a very confusing concept at 2 AM.

Why the Boundary Lines Matter

There’s a lot of talk about the "Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Alaska Map" in the context of oil.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

The boundary lines on the northern edge are where the legal battles happen. To the west of the Canning River is state land and the Alpine oil field. To the east is the refuge. From the air, the land looks identical. It’s all a vast, soggy plain. But the line on the map represents a massive shift in how the land is managed.

The Gwich'in people call the Coastal Plain "Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit," or "The Sacred Place Where Life Begins." For them, the map isn't about boundaries; it’s about a spiritual connection to the caribou. When you see the border of the refuge on a map, you’re seeing a line between industrial development and one of the last places on Earth where the ecosystem functions exactly as it did 10,000 years ago.

Realities of the Trip

If you’re actually planning to go, don’t just look at a general map. You need the USGS 1:63,360 scale quadrangles.

Specifically, you’re looking for names like "Mt. Michelson," "Beechey Point," or "Demarcation Point." These are the quadrants that cover the heart of the refuge. You can download them for free from the USGS store, but get them printed on Tyvek or another synthetic material.

- Weight Matters: Don't bring the whole atlas. Cut the maps to only the areas you’ll be in, plus a five-mile buffer.

- Contour Lines: Learn to read them. In the Arctic, a tiny change in elevation can be the difference between a dry campsite and sleeping in a swamp.

- The "V" Shape: When contour lines cross a river, they form a "V" that points upstream. Remember that when you’re disoriented in a canyon.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the sheer emptiness. On most maps of the Lower 48, there’s a town every ten miles. In the refuge, you can walk for three weeks and not see a single sign of human existence. No fence, no trail, no trash. It’s beautiful, but it’s also indifferent to your presence. The map is your only bridge back to civilization.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Explorer

Don't just stare at the screen. If you're serious about understanding or visiting this area, you need to treat the cartography like a language.

- Order Physical Quads: Go to the USGS Store and search for the 1:63,360 scale maps for the Brooks Range. Feeling the paper and seeing the true scale is a reality check.

- Learn Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM): Latitude and Longitude are great, but UTM is often easier for ground navigation in the wilderness because it uses a metric grid.

- Cross-Reference with Satellite Imagery: Use Google Earth or Sentinel Hub to look at the actual river channels. Compare them to your topo map. You’ll quickly see how much the water moves.

- Study the 1002 Area Boundaries: If you are a hunter or a researcher, knowing exactly where the refuge ends and state land begins is vital for legal reasons. The fines for being on the wrong side of the line are no joke.

- Check the "Public Information Map": The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) maintains a specific map for the Arctic Refuge that shows current administrative boundaries and land status (Native-owned vs. Federal). This is crucial because some land within the refuge borders is actually private.

Mapping the Arctic isn't a finished job. It's a constant process of observing a landscape that refuses to stay still. Whether you're an armchair traveler or someone packing a bush plane, the arctic national wildlife refuge alaska map is more than just geography; it's a testament to one of the few places left where humans aren't the ones in charge of the lines.