If you look at a modern GPS, Japan is a clear, shivering crescent of four main islands. But honestly, if you could hand a smartphone to a court official in the Nara period, they wouldn't recognize the shape. The map of ancient japan isn't just a geographic record; it’s a shifting political statement that changed every time a new Emperor wanted to prove they actually controlled the wilderness.

People usually imagine ancient maps as dusty, accurate scrolls. They weren't. Early Japanese cartography was about power, not precision. It’s kinda wild to think that for centuries, the "map" was basically just a series of lines connecting the capital to various tax-paying provinces, leaving the rest of the mountainous terrain as a big, terrifying blank space.

The Gyoki Style and the Birth of the "Sixty-Odd Provinces"

The earliest recognizable map of ancient japan is usually attributed to a monk named Gyoki. Now, did Gyoki actually sit down and draw every coastline? Probably not. But his name became synonymous with a specific style of mapping that stuck around for nearly a thousand years.

In these Gyoki-zu maps, Japan looks sort of like a cluster of balloons. There’s no attempt at "true" North or accurate longitudinal scaling. Instead, you see Kyoto (the center of the universe, obviously) and then these rounded blobs representing provinces like Yamato, Izumo, and Kibi. It’s basically a subway map of the 8th century. It tells you where the stops are, but it doesn't tell you what the ground actually looks like.

You’ve gotta realize that back then, the borders were fluid. The Emishi people in the north—modern-day Tohoku—weren't part of the "map" for a long time. They were the "outside." When you look at an old map from the Heian period, the northern tip of Honshu often just fades into nothingness or is labeled with vague terms for "barbarian lands." Mapping was a way of saying, "This is where the Emperor’s law stops."

Why the Coastlines Look So "Wrong" in Old Records

If you’ve ever compared a 14th-century Japanese map to a European one from the same era, the Japanese ones often look "worse" to a modern eye. But that’s a huge misconception. The Japanese weren't bad at math. They just didn't care about the same things.

The map of ancient japan was designed for the Gokishido system. This was the "Five Home Provinces and Seven Circuits" layout. Basically, the map was a tool for tax collectors and messengers. It highlighted the San'yodo and San'indo roads. If a mountain didn't have a government-sanctioned road through it, it basically didn't exist on the official map.

✨ Don't miss: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

I was reading some research by Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry, who wrote The Culture of Copying in Japan. She points out that mapping was a "social act." When a local lord (daimyo) commissioned a map, he wasn't looking for topographical accuracy. He wanted to show his castle, his rice fields, and his connection to the capital. The actual shape of the bay? Secondary. Total afterthought.

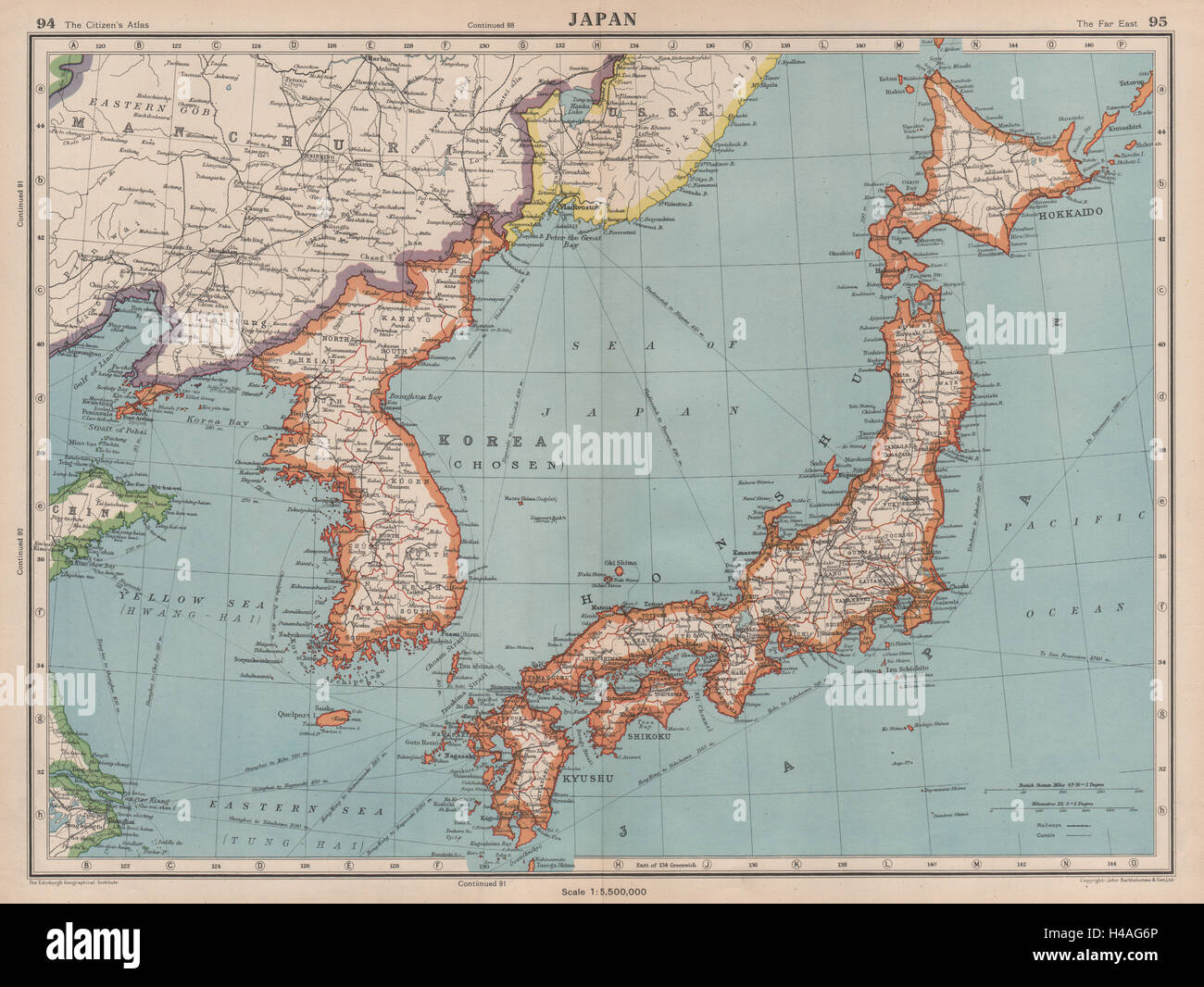

The Weird Case of Hokkaido (Ezo)

Hokkaido is huge. It’s the second-largest island in Japan today. But on almost every map of ancient japan before the 1800s, it’s either a tiny speck or completely missing.

The Japanese called it Ezo. To the people in Kyoto, it was basically another planet. It wasn't until the Matsumae clan started establishing firm trading posts that the island began to take shape on paper. Even then, early cartographers often drew it as a small island or even a peninsula of Russia (Tartary). It’s a great example of how maps represent what we know, not what is actually there.

How the Mongol Invasions Changed the View

In the late 1200s, everything changed. When Kublai Khan decided he wanted Japan, the Shogunate realized they had a massive problem: they didn't actually know their own coastline well enough to defend it everywhere.

This sparked a surge in more detailed coastal mapping. You start seeing the "Ino" style much later, but the seeds were sown here. Military necessity is a hell of a drug for accuracy. Suddenly, knowing the exact depth of Hakata Bay was more important than having a pretty drawing of a temple.

The map of ancient japan started becoming a tool of war. You can see this in the way the Kamakura and Muromachi periods began cataloging "shoen" (private estates) with much more grit and detail. They were counting every bushel of rice and every possible landing beach.

🔗 Read more: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

The Ino Tadataka Revolution: The Map That Finally Got It Right

Fast forward a bit—okay, a lot—to the late 18th century. This is where the map of ancient japan finally stops looking like a collection of grapes and starts looking like the Japan we know.

Enter Ino Tadataka. This guy is a legend. He was a retired sake brewer who decided, at the age of 50, to go to Edo and study astronomy. He then spent 17 years walking—literally walking—the entire coastline of Japan.

- He took over 70 million steps.

- He used basic surveying equipment and the stars.

- He produced the Dai Nihon Enkai Yochi Zenzu.

When his map was finished, it was so accurate that it was kept as a state secret. The Shogunate didn't want foreign powers having that kind of intel. When British surveyors showed up decades later and saw Ino’s maps, they basically threw their own charts away. They couldn't believe a guy with a compass and a string had beaten them at their own game.

Common Mistakes People Make When Researching This

Most people go to Google Images, type in map of ancient japan, and click on the first colorful thing they see. Usually, that’s a 19th-century "reproduction" or a map from a video game like Total War: Shogun 2.

Real ancient maps are rare and often hard to read because they use "inverted" perspectives. Some maps were meant to be read from the center out, meaning you had to rotate the physical scroll as you looked at different provinces. If you’re looking at a map and it seems "upside down," it’s probably because it was designed for someone sitting in the middle of a room, not hanging on a wall.

Another thing: names change. A lot. Tokyo was Edo. Osaka was Naniwa. If you're looking for a specific city on a 1,000-year-old map, you're going to have a bad time unless you know the archaic kanji.

💡 You might also like: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

Actionable Steps for Exploring Ancient Japanese Geography

If you actually want to see these things or understand the layout of old Japan without getting lost in academic jargon, here is how you should actually do it.

Check the Nichibunken Database. The International Research Center for Japanese Studies has a massive digital archive of "Earthquake Maps" and old provincial charts. It’s free, and the resolution is high enough to see individual houses in 17th-century Kyoto.

Visit the Ino Tadataka Museum in Sawara. It’s a bit of a trek from Tokyo, but if you want to see the actual instruments used to create the first "real" map of ancient japan, this is the place. You can see his original notebooks, which are surprisingly messy and very human.

Look at "Meisho Zue" (Illustrated Guidebooks). Instead of looking for a single map of the whole country, look for these. They were the Fodor’s guides of the Edo period. They provide hyper-local "bird's-eye" views of specific shrines and towns. They give you a much better feel for the "vibe" of the landscape than a flat political map ever could.

Learn the "Goki Shichido" structure. If you can memorize the five provinces around Kyoto and the seven "roads" (like the Tokaido), suddenly every old map starts making sense. You’ll stop seeing a mess and start seeing a logical system of movement and control.

Use the University of Tokyo’s "Historiographical Institute." They have an online gallery called "The World of Maps." It’s one of the best ways to see how the Japanese view of the world expanded from a small island to a global player.

Understanding the map of ancient japan is really about understanding how the Japanese people saw themselves. They weren't just drawing land; they were drawing their place in a divine landscape, where mountains were gods and the sea was a boundary to be respected. The next time you see a modern map of Japan, just remember that for most of history, that crisp coastline was a mystery, a myth, or a carefully guarded secret.