You’re staring at a screen. Maybe it’s a flickering GPS unit in the middle of a dead zone in the Mojave Desert, or perhaps you're just bored and looking at Google Maps on your phone while waiting for a latte. Either way, those tiny little numbers—the decimals and the degrees—are the only reason you aren't currently lost in a cornfield. Most people treat a longitude and latitude map USA like a piece of background noise. It’s just there. But honestly, the grid system that chops up the United States is a masterpiece of messy, human-designed geometry that bridges the gap between a giant, lumpy rock floating in space and the turn-by-turn directions to the nearest Taco Bell.

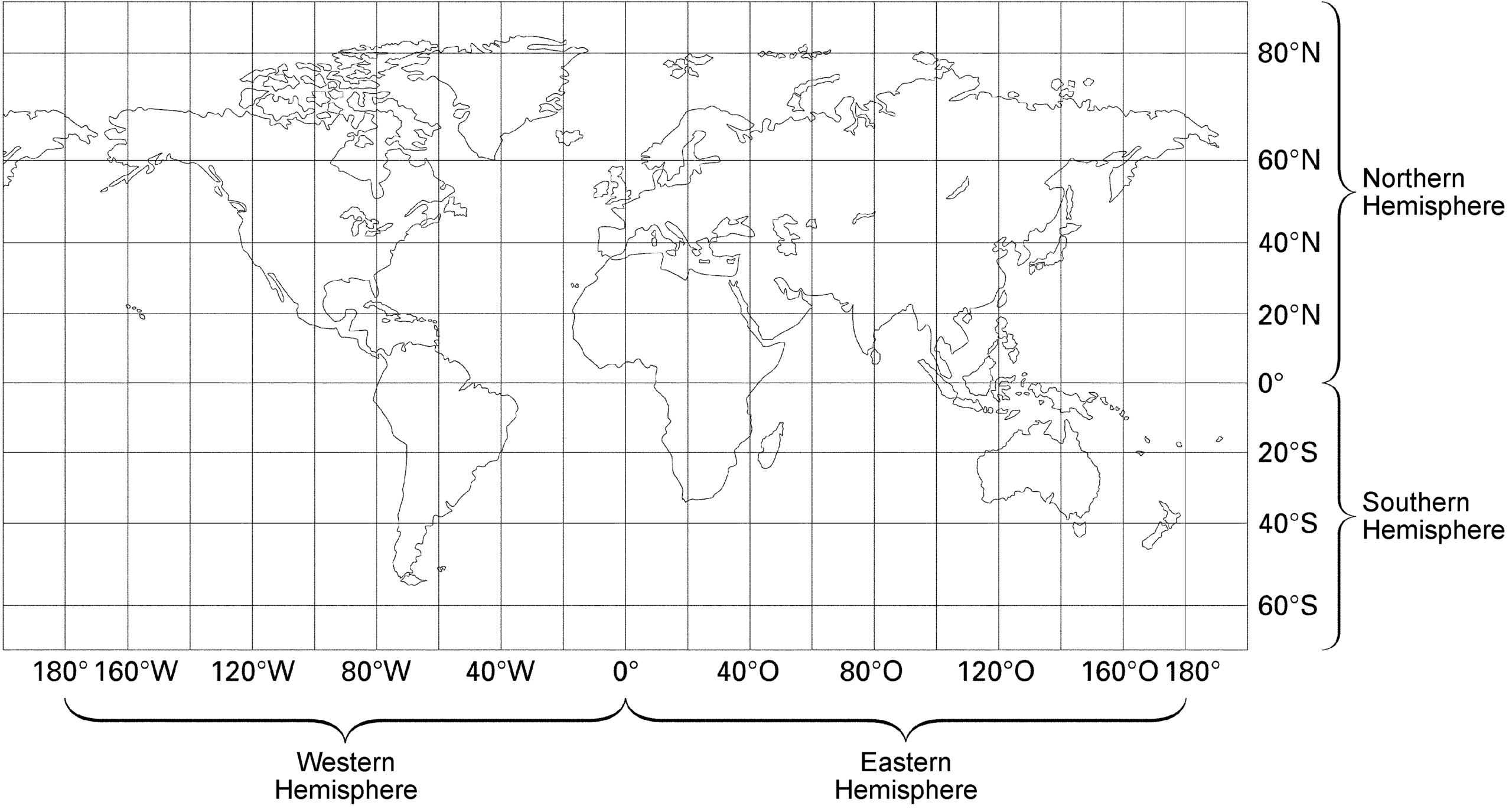

The US isn't a perfect square. Obviously. It’s a jagged, sprawling landmass that stretches across roughly 58 degrees of longitude and about 25 degrees of latitude. When you look at a map, you’re seeing a flat lie about a round truth.

The Invisible Grid Over the Lower 48

Maps are liars. Since the Earth is an oblate spheroid—basically a ball that someone sat on slightly—you can't just peel it like an orange and lay it flat without tearing something. This is why a longitude and latitude map USA looks different depending on who made it. If you’re using a Mercator projection, Maine looks like it's trying to escape into the Atlantic, and everything up north looks bloated. Most modern digital maps use Web Mercator, which is great for zooming in on your house but kind of terrible for understanding the actual scale of the country.

Latitude lines, or parallels, are the easy ones. They run east-west. They stay the same distance apart forever. In the US, the "bottom" of the contiguous states sits around the 24th parallel (the tip of Florida), while the "top" hits the 49th parallel, which forms that long, straight-ish border with Canada.

Longitude is where things get weird. These lines (meridians) run north-south and meet at the poles. This means that a degree of longitude in Miami is wider than a degree of longitude in Seattle. As you move toward the North Pole, the world literally shrinks. This makes calculating distance in the US a bit of a headache for surveyors. If you’re in the Florida Keys, one degree of longitude is about 65 miles. By the time you get to the Canadian border in North Dakota, that same degree has shriveled to about 46 miles.

Where the Lines Actually Hit

Let’s talk about the "Center" of the country. If you go to Belle Fourche, South Dakota, you’ll find a monument for the geographic center of the entire United States (including Alaska and Hawaii). The coordinates? Roughly $44^\circ 58' N, 103^\circ 46' W$. But if you only care about the lower 48, you have to head to Lebanon, Kansas.

It’s a weird feeling standing there. You're at $39^\circ 50' N, 98^\circ 35' W$. It’s just a park with a small stone monument. But this spot represents the mathematical balance of a massive continent.

- The 100th Meridian: This is arguably the most important line of longitude in the US. It roughly bisects the country. Historically, it’s the "dry line." To the east, you get enough rain to grow crops without much help. To the west? You’re in the rain shadow of the Rockies, and everything changes. Agriculture, population density, and even the "vibe" of the towns shift once you cross this line.

- The 45th Parallel: This is the halfway point between the Equator and the North Pole. It cuts through Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ontario (Canada), New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. There are signs all over these states bragging about being "halfway to the pole," though because of the Earth's bulge, the actual halfway point is a few miles off.

Why GPS Numbers Look Different

If you’ve ever tried to type coordinates into a search bar, you’ve probably seen two different languages.

💡 You might also like: Apple Music for Free Trial: The Smart Way to Get It Without Paying

First, there’s DMS: Degrees, Minutes, Seconds. It looks like this: $38^\circ 53' 23'' N, 77^\circ 00' 32'' W$. That’s the US Capitol. It’s an old-school, seafaring way of talking. Then there’s Decimal Degrees (DD), which is what your phone uses: $38.8897, -77.0089$.

Note the negative sign on the longitude. In the world of digital mapping, everything West of the Prime Meridian (which runs through Greenwich, England) is negative. Since the entire USA is in the Western Hemisphere, every single longitude coordinate for a longitude and latitude map USA will be a negative number. If you forget that minus sign, you’ll find yourself looking at coordinates in China or Kyrgyzstan instead of Kansas.

The Four Corners and Surveying Errors

We like to think our borders are perfect. They aren't.

The Four Corners Monument—where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona meet—is a famous spot. People love to put one limb in each state. For years, a rumor floated around that the monument was "wrong" by several miles because of 19th-century surveying errors.

✨ Don't miss: The Latest NVG Tech: Why Everyone Is Talking About Fusion Now

The truth is a bit more nuanced. The surveyors back then were using chains and transit telescopes. They were literally dragging metal links through the desert. By modern GPS standards, yes, the monument is about 1,800 feet east of where it was "supposed" to be based on the original 1868 degrees. But here’s the kicker: in legal terms, the survey is the boundary. Once the monument is set and agreed upon, it doesn't matter if the math was slightly off. The line is where the heavy stone says it is.

Mapping the Deep Nuance of US Geography

When you look at a longitude and latitude map USA, you’re seeing the skeleton of American expansion. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created the Public Land Survey System (PLSS). This is why if you fly over the Midwest, everything looks like a giant checkerboard. The government wanted to sell land in neat little squares.

Contrast that with the East Coast. Places like Virginia or Massachusetts were mapped using "metes and bounds." Their borders are based on "that big oak tree" or "the bend in the creek." It’s chaotic. But as you move West across the longitude lines, the grid takes over. The lines get straighter. The corners get sharper.

How to Use This Information

If you are actually trying to navigate or build something using these coordinates, you need to understand Datums. A datum is basically a starting model of the Earth's shape.

The most common one is WGS 84. This is what GPS uses. However, if you are looking at an old USGS (United States Geological Survey) paper map, it might be using NAD 27 (North American Datum of 1927). If you mix these up, your "exact" point could be off by 50 or 60 meters. That might not matter if you’re looking for a park, but it matters a lot if you’re drilling a well or flying a drone.

💡 You might also like: Why You Haven't Heard Back From the Threads Recruiting Team Email

Actionable Steps for Using Coordinate Maps

- Check Your Settings: If you’re using a handheld GPS for hiking in the US, ensure your "Map Datum" matches the map you’re holding. Use WGS 84 for digital work and check the legend on paper maps.

- Format Matters: When sharing coordinates, use Decimal Degrees ($34.0522, -118.2437$) for easy copy-pasting into Google Maps. Use DMS if you're communicating with maritime or aviation professionals.

- The "West" Rule: Always remember that in the US, longitude is negative. If you're using a tool that asks for "E/W," select West. If it’s just a number field, put a minus sign before the longitude.

- Verify High-Precision Needs: For property lines or construction, never rely on a consumer-grade longitude and latitude map USA. Consumer GPS (phones) are usually accurate to about 3–5 meters under an open sky. For anything precise, you need a surveyor using RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) positioning, which gets down to centimeter-level accuracy by using a fixed base station to correct satellite drift.

The grid isn't just a bunch of lines; it's a living document of how we've claimed, sold, and navigated this specific chunk of the planet. Next time you see those coordinates, remember you're looking at a code that tells you exactly where you stand on a spinning sphere. It's pretty cool when you think about it.

To get started with your own mapping project, you can download official shapefiles and coordinate data from the USGS National Map or use the NOAA Shoreline Data Explorer for coastal coordinates. These are the gold standards for factual, government-verified spatial data in the United States.