You’re standing on Cemetery Ridge. It’s quiet now. But if you look at a map of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg sits there like the hub of a wheel, with ten roads screaming out from the center in every direction. That’s why it happened there. It wasn't some grand strategic choice by Robert E. Lee or George Meade to fight on that specific patch of dirt. It was the roads. They all led to Gettysburg. If you’re planning a trip or just trying to wrap your head around how 160,000 men ended up in a small town of 2,400 people, you have to understand the geography.

The map is the story.

Pennsylvania’s topography is a messy mix of rolling hills and jagged ridges. By the time you get to Adams County, the South Mountain range is looming to the west. To the east, it’s open farmland. Gettysburg is the choke point. Honestly, if you look at a modern satellite view, you can still see the "spokes" of the wheel—the Baltimore Pike, the Emmitsburg Road, the Chambersburg Pike. In 1863, these weren't just lines on paper; they were the only way to move thousands of wagons and cannons without getting stuck in the mud.

Why the Map of Pennsylvania Gettysburg Layout Decided the Battle

Most people think battles are just two lines of guys shooting at each other in a field. Not this one. This was a race for the high ground. Look at a topographic map of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg specifically, and you'll see a fishhook. That’s the shape the Union army eventually took.

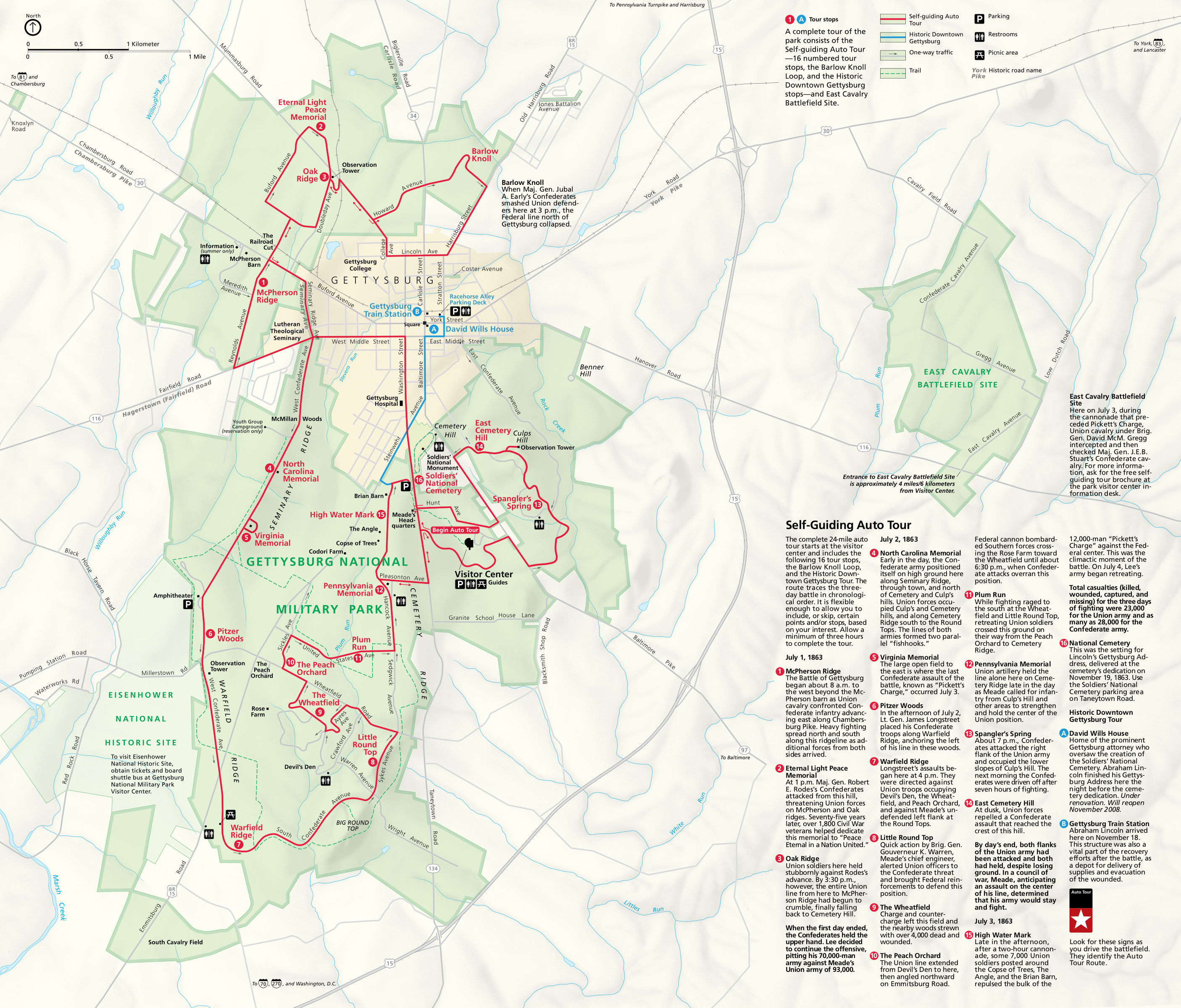

The "hook" starts at Culp's Hill, curves around Cemetery Hill, and runs down the spine of Cemetery Ridge to the Round Tops. It’s a defensive masterpiece of nature. Because the Union held the "inside" of the hook, they could move troops back and forth quickly. The Confederates were on the "outside," meaning if they wanted to move men from one wing to the other, they had to march miles around the perimeter. Geography gave the North a massive time advantage.

It's kinda wild when you think about it. If the Union hadn't arrived from the south and east just as the Confederates were coming in from the north and west, the whole map of the war looks different. The town itself was actually quite prosperous back then. It had a carriage industry. It had a college. It wasn't some backwater; it was a logistical goldmine because of those ten roads.

The Famous Ridges You Can See Today

If you grab a National Park Service map today, you’ll see two main parallel ridges: Seminary Ridge (where the Confederates were) and Cemetery Ridge (the Union line). Between them is about a mile of open, undulating farmland.

That mile is where Pickett's Charge happened.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

When you stand on Seminary Ridge and look across, it looks flat. It isn't. There are "dead spots" where the ground dips and you can’t see the other side. This is why maps can be deceiving. A flat 2D map doesn't show you the swales that could hide an entire regiment or the rocky outcroppings of the Devil’s Den that turned a simple infantry advance into a nightmare of boulders and snipers.

Navigating the Modern Battlefield

If you're heading there, don't just wing it. The park is huge. Over 6,000 acres.

You’ve basically got three ways to see it. You can do the auto tour, which follows the numbered markers. It’s fine. It’s the standard. But if you really want to feel the ground, you need to get off the main loop. Most people skip the First Day’s battlefield north of town. Big mistake. That’s where the cavalry held the line and where the whole mess started near the McPherson Farm.

- The Auto Tour: This is the 24-mile route. It takes about 2 to 3 hours if you’re rushing, but honestly, give it a full day.

- The High Water Mark: This is the center of the Union line. It’s where the most monuments are. It’s also where the crowds are.

- Little Round Top: This is the legendary hill on the far left of the Union line. It was closed for a long time for massive restoration work—the sheer volume of tourists was literally eroding the mountain—but it’s the best view on the map. You can see the whole valley from there.

The map of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg region is also full of "witness trees." These are trees that were actually alive during the battle. There’s one near the National Cemetery that still has lead bullets embedded deep in its trunk, though the bark has grown over them now.

Getting There: The Logistics

Gettysburg is about 38 miles south of Harrisburg and 80 miles north of Washington, D.C.

Most people drive in via US-15 or PA-30 (the old Lincoln Highway). Route 30 is the one the Confederates used to come in from the west. If you drive that road today, you’re literally driving the same path as the Army of Northern Virginia. It’s surreal. The town itself is still a grid, very easy to navigate, though the "Diamond" (the central square) is now a roundabout that confuses people who aren't used to Pennsylvania driving.

The Parts of the Map Nobody Talks About

Everyone goes to the Angle. Everyone goes to the Peach Orchard.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

But have you looked at the East Cavalry Field? It's about three miles east of the main park. Most visitors don't even know it exists. This is where George Armstrong Custer (yeah, that Custer) fought a massive horseback battle against Jeb Stuart. If Stuart had broken through there, he would have ended up in the Union rear, and Pickett’s Charge might have actually worked.

The map of the East Cavalry Field is wide open. It’s beautiful, silent, and haunting.

Then there’s the town itself. During the three days of fighting, the town was a "no man's land." Sharpshooters were in the attics. Civilians were huddling in cellars. If you look at a map of the historic district, you can still find houses with "shell markers"—actual artillery rounds that hit the bricks and never exploded, or were later cemented back in as memorials. The Shriver House and the Jennie Wade House are the big ones, but just walking the side streets tells a better story than any textbook.

Understanding the Elevations

The South Mountain range acts as a curtain. In 1863, Lee used the mountains to hide his army's movement as he moved north. The Union was on the other side, playing a guessing game. This is why the map of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg is so crucial to military historians. It’s a study in "the fog of war."

When the fog cleared, the two armies were slammed together by the gravity of the road system.

Practical Tips for Your Visit

Don't trust your GPS blindly. Some of the smaller park roads are one-way or closed seasonally.

- Start at the Visitor Center: Seriously. Buy the map there. The digital ones are okay, but a physical topographic map lets you see the ridges in relation to each other in a way a phone screen can't.

- Check the weather: Adams County gets humid. Like, "air you can wear" humid. In July, it's brutal. If you're hiking the trails, bring more water than you think you need.

- The National Cemetery: This is where Lincoln gave the Gettysburg Address. It’s a somber, perfectly manicured arc of graves. It’s located on Cemetery Hill, which was the literal "hinge" of the Union line.

A lot of people ask if you can see it all in one day. Sorta. You can see the highlights. But if you want to understand why the 20th Maine held the flank, or why Ewell didn't take the hill on the first night, you need time to walk the ground. You need to see the slopes.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

What Most People Get Wrong About the Geography

There’s a myth that the battle was fought over shoes. It’s a great story—the idea that Confederate soldiers were barefoot and headed into town to find a shoe factory.

There was no shoe factory.

There were shoes in town, sure, but the battle happened because Gettysburg was the only place where all those roads intersected. It was a collision of necessity. If you look at the map of Pennsylvania, Gettysburg is the only logical place for two massive, scattered armies to concentrate.

Another misconception: that the "High Water Mark" was the end of the war. It wasn't. The war went on for two more bloody years. But the map of the United States was saved on those ridges. If Lee had won, he had an open road to Harrisburg or Philadelphia. The stakes were that high.

Actionable Steps for Your Geography Tour

To truly appreciate the scale of this place, start your morning at the Eternal Light Peace Memorial on Oak Hill. From there, you can see the entire panorama of the first day's fight. Then, move to the Pennsylvania Memorial on Cemetery Ridge. It’s the biggest monument on the field. You can actually climb to the top of it. From that height, the "map" comes to life. You can see the Round Tops to your left, the town to your right, and the Confederate woods straight ahead.

If you want to avoid the crowds, hit the trails around Culp’s Hill in the afternoon. It’s heavily wooded and looks much more like it did in 1863 than the cleared fields of the Pickett's Charge area. The earthworks—the trenches the soldiers dug—are still visible as mounds in the dirt. It’s one of the few places where you can see the literal physical scars on the map.

Take a physical map. Turn off your phone for an hour. Walk from the Bliss Farm site toward the Bryan House. Feel the rise and fall of the ground. That’s how you actually learn Gettysburg. It’s not in the dates or the names of the generals; it’s in the dirt and the way the roads pull everything toward that one small square in the middle of Pennsylvania.

Head to the Gettysburg National Military Park website to check for road closures before you go, especially around Little Round Top, as conservation efforts are ongoing to keep the battlefield from being literally walked into oblivion. Once you're there, grab the official park map at the counter—it's the most accurate guide you'll find for the winding, one-way avenues that define the park today.