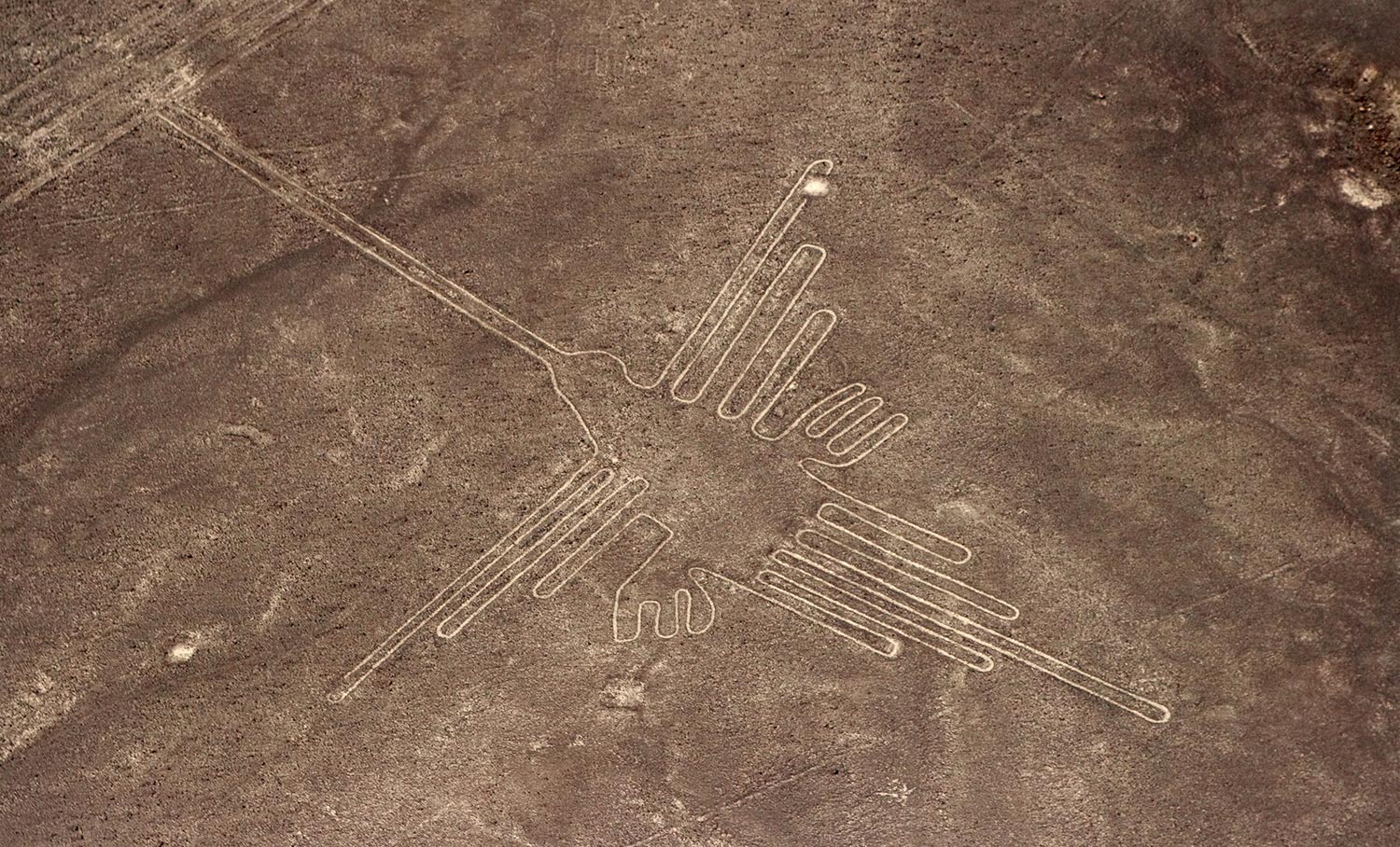

You’re standing on a rusted observation tower in the middle of the driest desert on Earth, squinting at the ground. To be honest, from up there, it looks like a mess of dirt roads and random scratches. But then the sun hits a certain angle, and suddenly, a massive hummingbird appears out of the dust. It’s huge. It’s perfect. And it makes absolutely no sense why it’s there.

If you’ve ever looked at a map of the Nazca Lines, you know the feeling of total bewilderment. We aren't just talking about a few doodles in the sand. This is a sprawling network of over 800 straight lines, 300 geometric figures, and 70 biomorphs—those famous animals and plants—covering nearly 170 square miles of the Peruvian coastal plain.

Most people think these are just pretty pictures for ancient gods to look at. That’s a bit of a simplification. When you actually study the layout, you realize the "map" isn't a map of the world—it’s more like a map of the community's soul, their water needs, and their terrifyingly precise understanding of geometry.

The Physical Reality of the Lines

The lines exist because of a weird geological quirk. The desert floor isn't just sand; it’s covered in a thin layer of iron oxide-coated pebbles. They're dark, almost black. If you scrape away just a few inches of those rocks, you hit light-colored lime and clay.

That’s it. No lasers. No aliens. Just some very patient people moving rocks.

But the scale is what gets you. The famous Spider is about 150 feet long. The Condor stretches nearly 450 feet. If you’re looking at a map of the Nazca Lines today, you’re seeing a palimpsest—layers upon layers of history where different generations of the Nazca culture (roughly 200 BCE to 600 CE) added their own marks.

📖 Related: Seminole Hard Rock Tampa: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s All About the Water

Ask a local archeologist like Johny Isla, and he’ll tell you straight up: the lines are about survival. This is one of the driest places on the planet. Rain basically doesn't happen.

Early researchers like Maria Reiche—the "Lady of the Lines" who spent decades sweeping the desert with a literal broom—thought the lines were an astronomical calendar. She believed the long straight lines pointed to where the sun and stars rose on certain dates. She wasn't entirely wrong, but she wasn't entirely right either.

Newer research, particularly from the University of Massachusetts and experts like David Johnson, suggests many of the lines actually track underground aquifers. In a desert, a map of the Nazca Lines is basically a blueprint for where the water is hiding. The geometric shapes often mark spots where rituals were held to pray for rain. They weren't just looking at the stars; they were desperately looking for a drink.

Why Some Figures Look "Wrong"

When you see the "Astronaut" (also called the Owlman) on a map, it looks like a modern guy in a space suit. It’s weird. It’s on a hillside, unlike most of the other figures.

Some people use this to claim extraterrestrial influence. Seriously, though? It’s much more likely a representation of a shaman or a fisherman. The Nazca people lived by the sea. They ate fish. They saw owls. Why would we assume it's a guy from Mars when it looks exactly like a stylized human figure from their own pottery?

👉 See also: Sani Club Kassandra Halkidiki: Why This Resort Is Actually Different From the Rest

The "Monkey" has a spiraling tail. This is fascinating because monkeys don't live in the Nazca desert. They live in the Amazon, on the other side of the Andes. This tells us the Nazca were travelers. Their map of the Nazca Lines includes things they saw on long-distance trade routes. It’s a record of their world, which was much bigger than just one patch of dirt.

The Modern Map is Growing

You’d think after a hundred years of flyovers, we’d have found everything. Not even close.

In recent years, researchers from Yamagata University in Japan have used AI and high-res satellite imagery to find nearly 200 "new" geoglyphs. Most of these are smaller and older, dating back to the Paracas period. These older ones are often found on hillsides, meant to be seen by people walking along the valley floors.

The later, larger Nazca lines—the ones we see on the famous map of the Nazca Lines—were meant to be walked upon. They are single, continuous paths. Think about that for a second. You don't "look" at the Spider; you walk the line of the Spider as part of a religious procession. It’s a labyrinth.

How to Actually See the Lines Without Ruining Them

If you go there, don't be that person who tries to walk on them. The ecosystem is incredibly fragile. The "varnish" on the rocks takes thousands of years to form. A single footprint can last for decades.

✨ Don't miss: Redondo Beach California Directions: How to Actually Get There Without Losing Your Mind

- The Tower: There’s a mirador (observation tower) along the Pan-American Highway. You can see the "Tree" and the "Hands" from here for a few soles. It’s okay, but it doesn't give you the scale.

- The Flight: This is the only way to see the map of the Nazca Lines in its full glory. Small Cessnas take off from the Maria Reiche Airport. Warning: they bank hard left and right so everyone can see. If you get motion sickness, take your meds early.

- The Palpa Lines: Most people skip these, but they’re older and arguably more complex. They’re located about 30 minutes north of Nazca.

The Great Misconception

The biggest lie people tell is that the lines can only be seen from the air.

Nope.

If you stand on the surrounding foothills, you can see plenty of them. The Nazca weren't stupid. They didn't build things they couldn't see. They used basic surveying tools—stakes and string—to create perfectly straight lines over miles of uneven terrain. Their "map" was a physical manifestation of their religion and their science, perfectly integrated into the landscape.

What to Do Next

If you are planning to visit or just want to dive deeper into the mystery, stop looking at the "aliens" documentaries. They're fun, but they rob the Nazca people of their actual genius.

Start by looking at the map of the Nazca Lines through the lens of hydrology. Look at where the lines intersect with dry riverbeds. Read the work of Anthony Aveni, who specializes in archaeoastronomy. He provides a much more grounded (literally) perspective on why these lines point where they do.

Book your flight for the early morning. The shadows at 7:00 AM or 8:00 AM make the lines pop. By noon, the sun is so high that the desert flattens out and the figures almost vanish. And honestly, bring a good camera with a polarizing filter. The glare off the desert is brutal, and without a filter, your photos will just look like a blurry brown mess.

Respect the site. The Pan-American Highway actually cuts right through the middle of the "Lizard" because, back in the day, people didn't realize what they were driving over. We know better now. The lines are a non-renewable resource of human history.