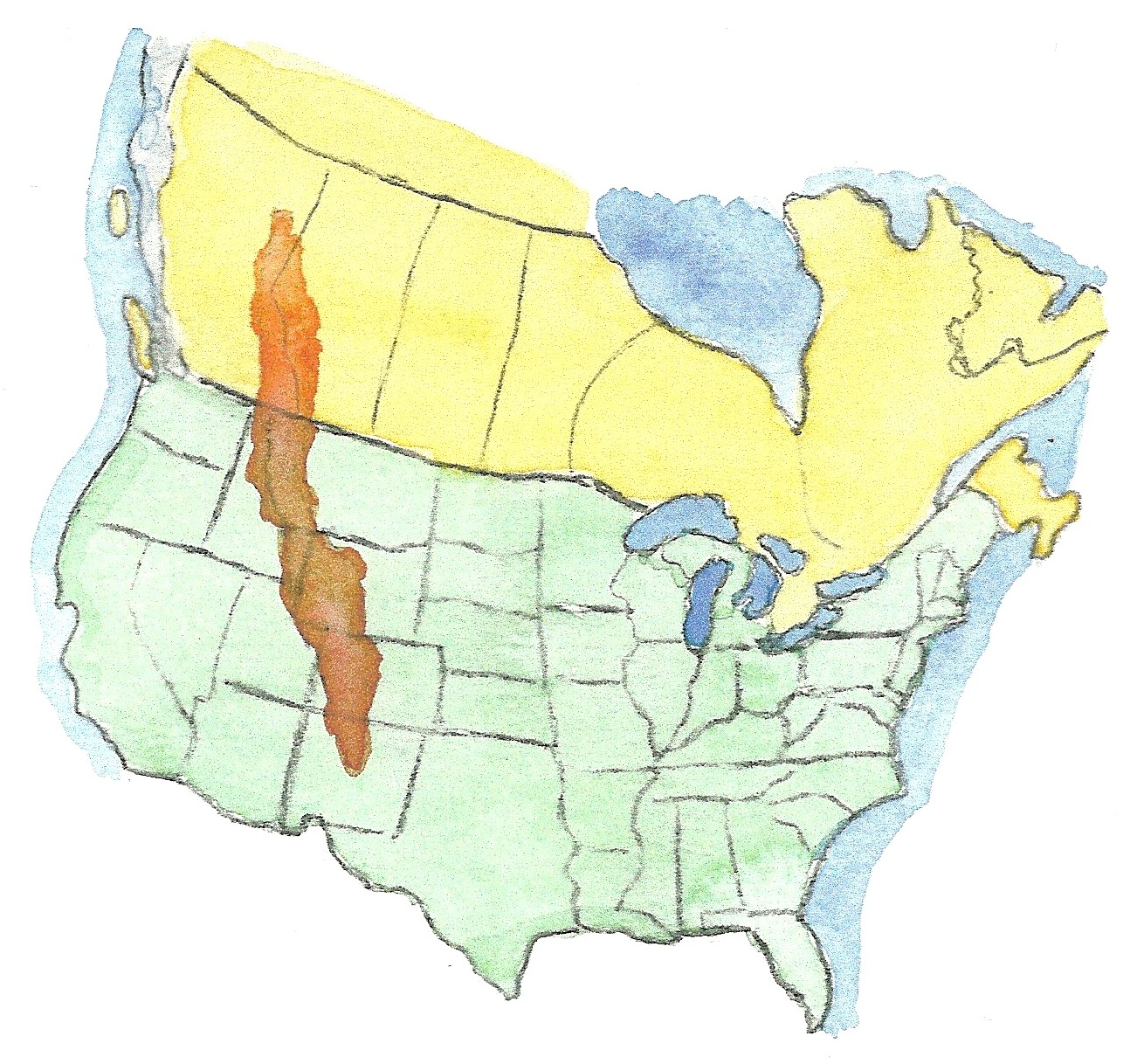

So, you’re looking at a map of the Rockies. It looks huge. Because it is. We are talking about a massive, jagged spine of granite and ice that stretches over 3,000 miles, running from the northernmost parts of British Columbia and Alberta all the way down into New Mexico. If you just glance at a digital screen, it’s easy to think it’s one continuous wall of rock, but the reality is much messier. It's a collection of roughly 100 separate mountain ranges.

Honestly, people get overwhelmed. They think they can "see the Rockies" in a weekend. You can't. Not even close. If you’re planning a trip, you need to understand that the "map" changes depending on who you ask. A geologist sees tectonic plates and the Laramide orogeny—that's the massive mountain-building event that happened about 80 to 55 million years ago. A hiker sees trailheads and elevation gains. A local? They just see home, and they probably wish you wouldn't crowd the secret spots.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Map of the Rockies

The biggest mistake is thinking the Rockies are just one thing. When people say "I'm going to the Rockies," they usually mean they're going to Banff in Canada or maybe Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. But look at a detailed map of the Rockies and you'll realize those two spots are 1,500 miles apart.

The range is basically split into several distinct sections. You’ve got the Canadian Rockies, which are incredibly jagged because they were heavily carved by glaciers. Then you have the Northern Rockies in Idaho and Montana—think Glacier National Park and the Bitterroot Range. Moving south, you hit the Middle Rockies through Wyoming (Yellowstone and the Tetons) and Utah. Finally, the Southern Rockies dominate Colorado and dip into New Mexico. Each of these zones feels like a different planet.

In the north, the peaks are often sharper, more "dramatic" in the traditional sense. In the south, the mountains are actually higher on average—Colorado alone has 58 "Fourteeners" (peaks over 14,000 feet)—but they can sometimes look like rolling hills from a distance because the base elevation of the surrounding land is already so high. Leadville, Colorado, sits at 10,152 feet. You're starting your hike at an altitude where people in the east are finishing theirs.

The Continental Divide: The Invisible Line

If you follow a map of the Rockies, you’ll see a line snaking through the middle called the Continental Divide. It’s the hydrological backbone of North America.

Rain on the west side flows to the Pacific.

Rain on the east side heads toward the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico.

📖 Related: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

It’s a simple concept, but standing on it feels different. At places like Independence Pass in Colorado or Logan Pass in Montana, you’re literally standing on the roof of the continent. It’s where the weather gets weird. You can have a sunny day on one side of a ridge and a full-blown blizzard on the other. That’s not an exaggeration. I’ve seen it happen in July.

Navigating the Major Hubs

When you start zooming in on a map of the Rockies, you’ll notice that human civilization has sort of huddled in the valleys. These are your basecamps.

The Canadian Gateway: Calgary and Banff

The Canadian Rockies are arguably the most photogenic. The Icefields Parkway (Highway 93) connects Lake Louise and Jasper. It’s widely considered one of the most beautiful drives on Earth. If you’re looking at the map, notice how the mountains here look like they were stacked like shingles. That’s "thrust faulting," where layers of rock were pushed over one another. It gives places like Mount Rundle that iconic, slanted look.

The Wild North: Whitefish and Missoula

In Montana, the mountains feel lonelier. You’ve got the Bob Marshall Wilderness—"The Bob"—which is one of the most remote areas in the lower 48. There aren't many roads on this part of the map. You’re in grizzly country here. Seriously. Carry bear spray and know how to use it.

The Central Spine: Jackson Hole

The Grand Tetons are a geographical anomaly. Most mountain ranges have foothills—the "appetizers" before the main course. The Tetons don't. They just explode out of the valley floor. On a map, look for the Teton Fault. That’s what created this vertical drama. It’s a 40-mile-long block of the earth’s crust that tilted upward.

The High Country: Denver and the I-70 Corridor

Colorado is the busiest part of the map. It’s where most people go because it’s accessible. But accessibility comes with a price: traffic. If you’re looking at a map of the Rockies and planning to drive from Denver to Vail on a Saturday morning, rethink your life choices. The "I-70 crawl" is real.

👉 See also: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

Climate and the "Blue Map"

Water is the most important thing on the map right now. The Rockies are the water tower for the American West. The Colorado River starts as a tiny trickle in Rocky Mountain National Park. By the time it reaches the Southwest, it’s keeping millions of people alive and powering massive dams.

But the map is changing.

Scientists like those at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) have been tracking glacier retreat for decades. In Glacier National Park, the number of glaciers has dropped from over 150 in the late 1800s to just 26 today. If you’re looking at an old paper map from the 70s, those white patches representing ice might not be there anymore. It’s a sobering reality of traveling in the high country today.

Winter is also shifting. The snowpack—which is basically a giant frozen reservoir—is melting earlier. For a traveler, this means "Mud Season" (that awkward gap between skiing and hiking) is getting longer and harder to predict.

Understanding Topographic Maps

If you are actually going to hike, a standard Google Map won't cut it. You need a topo map.

You’ve seen them—those maps with the "brown squiggly lines" (contour lines). Each line represents a specific elevation. When the lines are close together, it’s steep. When they’re far apart, it’s flat.

✨ Don't miss: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

- Green areas are forests.

- White/Grey areas are above the treeline (tundra).

- Blue lines are creeks that might be dry by August.

Pay attention to the "aspect." A north-facing slope on the map will hold snow much longer than a south-facing one. In June, you might find a dry trail on the south side of a mountain, while the north side is still buried in four feet of slush. This is the kind of detail that keeps you from getting stuck.

Wildlife Corridors: Sharing the Map

The Rockies aren't just for us. They are one of the last great strongholds for megafauna in North America. When you look at a map of the Rockies, try to see the "Y2Y" initiative—Yellowstone to Yukon.

This is a massive conservation effort to keep the mountains connected. Animals like wolves, elk, and wolverines need huge ranges to survive. If we fragment the map with too many roads and fences, the populations die out. In places like Banff, they’ve built massive overpasses covered in grass and trees just so grizzly bears can cross the highway without getting hit. It’s working.

When you’re driving these routes, remember you’re a guest in their living room. In Estes Park, Colorado, the elk basically own the town. They don't care about your "right of way."

Actionable Steps for Using a Map of the Rockies Effectively

If you’re serious about exploring this region, don't just wing it.

- Download Offline Maps Early. Cell service in the Rockies is a joke. Once you enter a canyon, your GPS will likely fail. Use Gaia GPS or AllTrails, but download the layers for offline use before you leave your hotel.

- Watch the Treeline. On your map, note the elevation of the treeline (usually around 11,000 to 11,500 feet in the Southern Rockies). Above this, there is no shelter from lightning. The "1:00 PM Rule" is real: be off the summit and heading down by noon to avoid afternoon thunderstorms.

- Check Seasonal Road Closures. High-altitude roads like Trail Ridge Road or Beartooth Highway are closed for half the year. Even if your map says it's the "fastest route," it might be under ten feet of snow in May. Check the Department of Transportation (DOT) sites for the specific state you're in.

- Respect the Scale. Use a scale bar. Distances look short on a phone, but 50 miles on a winding mountain road can take two hours. Give yourself twice as much time as you think you need.

- Get a Paper Map. Honestly. A National Geographic Trails Illustrated map is indestructible, doesn't need batteries, and gives you a "big picture" view that a 6-inch screen never will.

The Rockies are a place of scale and consequence. The map is your best tool, but it's only as good as your ability to read what's between the lines. Whether you're chasing the "Golden Hour" for photography or trying to find a quiet campsite away from the crowds, understanding the layout of these peaks is the difference between a great trip and a dangerous one.

Keep your eyes on the horizon, but keep your thumb on the map. The terrain doesn't care about your plans, so adapt to it. Get out there and see the scale for yourself.