You're standing at the helm, the salt air is thick, and the sun is beating down on the fiberglass. You look at your screen. Then you look at the water. They don't match. This is the first thing every boater realizes when they start obsessing over a map of Intracoastal Waterway routes: the water moves faster than the ink dries on a chart.

The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) is a 3,000-mile stretch of bays, rivers, sounds, and man-made canals. It’s a marvel. It runs from Norfolk, Virginia, all the way down to the tip of Florida and then hangs a right over to Texas. But if you think a single map is going to save you from grounding your keel in a shifting North Carolina inlet, you’re in for a very expensive tow.

What a Map of Intracoastal Waterway Actually Shows (And What It Hides)

Most people start with the "Magenta Line." If you look at any official NOAA chart or a digital navigation app like Navionics, you’ll see that bold, pinkish-purple line snaking through the channels. It’s the promised land. It’s supposed to be the deepest, safest path.

Except it isn't. Not always.

The Magenta Line was actually removed from official charts for a few years because it was so wildly inaccurate in places that boats were ending up on sandbars while following it religiously. It’s back now, but seasoned cruisers treat it like a suggestion, not a law. A map of Intracoastal Waterway sections in the Georgia Lowcountry, for instance, might show a clear path, but at low tide, that path might only have three feet of water. If you draw four feet? You’re sitting there for six hours waiting for the tide to come back.

The ICW is divided into two main sections. You’ve got the Atlantic side and the Gulf side. They are totally different beasts. The Atlantic side is older, more scenic, and frankly, more prone to shoaling. The Gulf side feels more industrial in spots but offers those wide-open stretches of the "Big Bend" where the ICW basically disappears and you’re just out in the open Gulf of Mexico for a while.

✨ Don't miss: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

Why Shifting Sands Ruin Your Navigation

Let’s talk about the Carolinas. Specifically, places like Lockwood’s Folly Inlet or Brown’s Inlet. These are what cruisers call "trouble spots."

In these areas, the map of Intracoastal Waterway changes every time a big storm rolls through. The Army Corps of Engineers tries to keep up with dredging, but nature is relentless. Currents rip through the inlets, carrying tons of sand that settles right in the middle of the channel. You can be looking at a brand-new electronic chart that says you have 10 feet of depth, and your sounder will suddenly scream "4 feet!"

This is why "crowdsourced" mapping has become the gold standard. Apps like Aqua Map or ActiveCaptain allow boaters to pin "hazards" in real-time. If someone grounded their boat at Mile Marker 340 yesterday, they’ll post a note. That’s more valuable than a map printed three years ago. You’ve got to be a bit of a detective. You’re looking at the official chart, checking the latest USCG Local Notice to Mariners, and then overlaying what Joe on his 40-foot trawler said happened two hours ago.

The Bridge Problem

Maps aren't just about water depth. They are about air draft.

If you’re on a sailboat with a 64-foot mast, the ICW is your personal nightmare. The "standard" bridge clearance is 65 feet. That gives you one foot of wiggle room. But guess what? Tides happen. If the map of Intracoastal Waterway says a bridge is 65 feet, that's usually at Mean High Water. If the tide is exceptionally high because of a full moon or a strong wind pushing water into the bay, that bridge might only be 63 feet.

🔗 Read more: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

Crunch.

There’s a famous bridge in Miami called the Julia Tuttle Bridge. It’s the "standard" 56-foot height, not 65. It catches people every single year who aren't looking at their charts closely enough. They see the Magenta Line and think they’re golden, only to realize too late that they have to go outside into the ocean to get around it.

The Different "Flavors" of the ICW Map

Navigating the ICW isn't a monolithic experience. It changes every few hundred miles.

- The Virginia/North Carolina Cut: Lots of cypress trees, dark "tea-colored" water from the tannins, and very narrow canals. Here, your map is mostly about staying between the green and red markers (squares and triangles).

- The Georgia Marshes: This is where the maps get confusing. The channels wind like a snake on caffeine. The tide range here can be 7 to 9 feet. A spot that looks like a massive lake at high tide becomes a tiny ribbon of water surrounded by mudflats at low tide.

- The Florida Corridor: High-rises, mansions, and bridges every five miles. Your map here is basically a schedule of bridge openings. Some open on demand; others only every 30 minutes. You’ll be hovering in the current, trying not to hit a billionaire’s yacht while waiting for a drawbridge to crawl upward.

Real-World Resources for the Smart Navigator

Don't just buy a paper chart and call it a day. You need a multi-layered approach to understand the map of Intracoastal Waterway nuances.

- NOAA Chart 11489: This is a classic for the St. Johns River to Palm Shores, but honestly, use the digital version via the NOAA Custom Chart tool. It’s updated weekly.

- Waterway Guide: This is basically the "Lonely Planet" for boaters. It gives you the "inside baseball" on marinas, fuel prices, and which bridges are currently under repair.

- The Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Surveys: This is the pro move. They publish "hydrographic surveys" which are literal scans of the bottom of the channel in high-stress areas. If you’re worried about a specific crossing, check the USACE website for that district. It’s the most accurate map you’ll ever find.

Honestly, the ICW is a social waterway. You learn more by listening to the VHF radio on Channel 16 or 13 than by staring at a screen. "Security, security, security... this is the tug Captain Phil southbound at Mile Marker 120, be advised shoaling on the green side." That’s your real map.

💡 You might also like: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

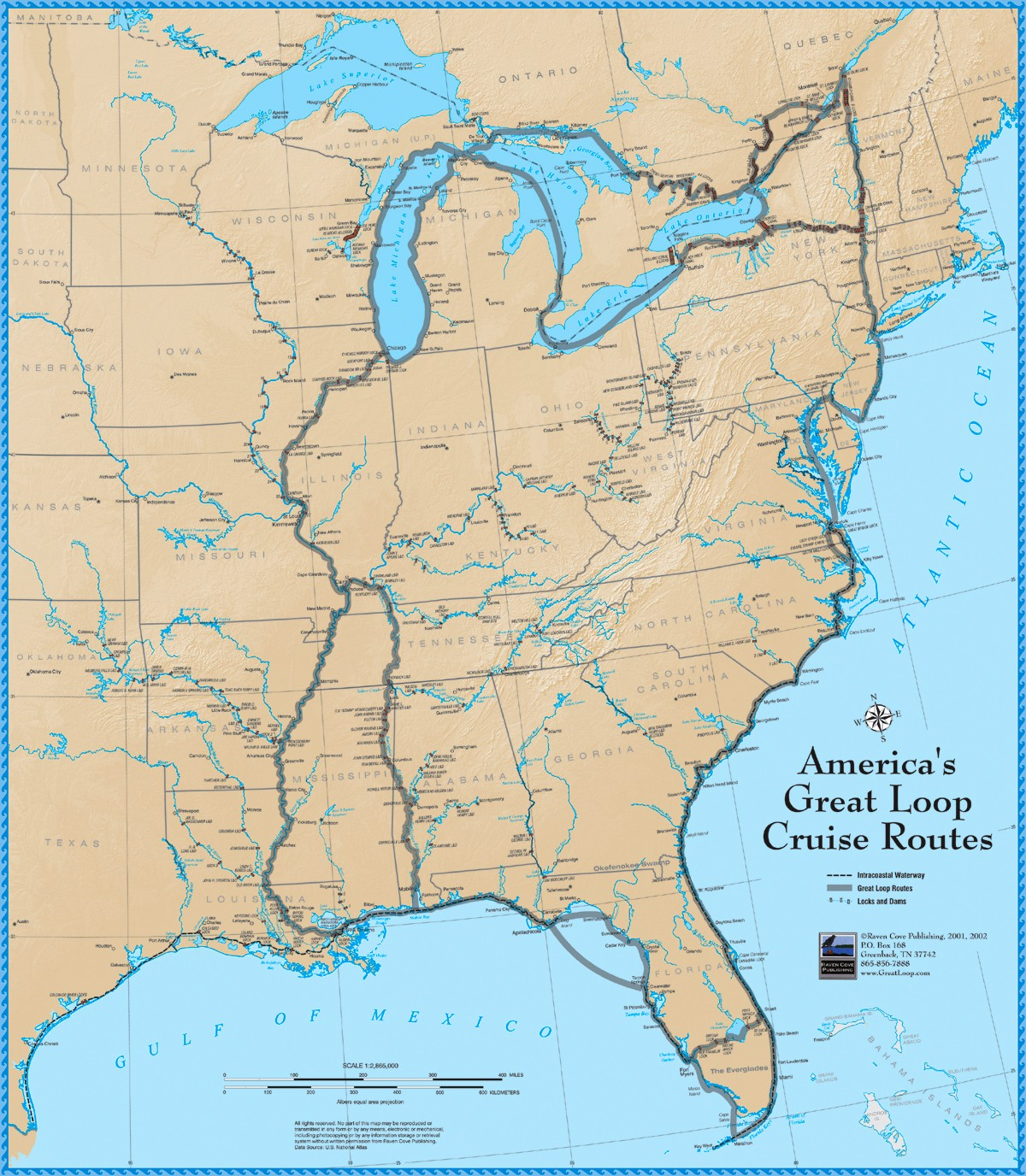

Dealing with the "Great Loop" Confusion

A lot of people looking for an ICW map are actually planning the "Great Loop." This is a 6,000-mile circumnavigation of the Eastern US. The ICW is just one leg of it. If you’re doing the Loop, your map needs to include the Hudson River, the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi River system.

The ICW portion of the Loop is often the most stressful because of the traffic. You aren't just sharing the water with other pleasure boats. You’ve got massive barges that take half a mile to stop. On a narrow map of Intracoastal Waterway canal, a barge owns the road. You move. They don't.

Technical Nuances: Red, Right, Returning?

In the ICW, the "Red, Right, Returning" rule gets a bit funky. Since you’re traveling a long distance rather than just entering a harbor, the rule is "Red on the Mainland side."

If you are traveling south from Norfolk to Florida, the mainland is on your right (starboard). So, you keep the red markers on your right. If you turn around and head north, the mainland is on your left, so the red markers should be on your left. To make it even more confusing, the ICW markers have little yellow triangles or squares on them to distinguish them from local channel markers.

Always follow the yellow. If the yellow triangle is on a red marker, treat it as a red ICW marker. If you see a red marker without a yellow symbol, it might be for a side channel leading to someone's house or a random marina, and following it could lead you straight into a jetty.

Essential Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

If you're planning to navigate using a map of Intracoastal Waterway data, don't just wing it.

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service is great until it isn't. The Alligator-Pungo Canal in NC is a dead zone. If your map relies on the cloud, you're navigating blind. Use an app that stores charts locally on your tablet.

- Check the "Bridge List": Create a cheat sheet of every bridge you'll hit that day, its height, and its opening schedule. Write it on a piece of tape and stick it to the helm.

- Trust Your Eyes Over the GPS: If the GPS says the channel is 50 feet to the left, but you see a line of crab pots and a breaking wave there, don't go there. Water color tells a story. Brown is deep, white is shallow, and "skinny water" usually looks clear and sandy.

- Watch Your Wake: A map doesn't tell you where the "No Wake" zones are as well as the signs on the pilings do. In Florida, the fines for throwing a wake in a manatee zone or a crowded marina are eye-watering.

- Verify the Datum: Ensure your GPS and your paper/digital maps are using the same "datum" (usually WGS84). If they aren't, your position could be off by dozens of feet—which is the difference between the channel and a rock wall.

The Intracoastal Waterway is a living thing. It breathes with the tides and shifts with the storms. Your map is just a snapshot of what someone saw a year ago. Use it as a guide, keep your eyes on the water, and always have a Plan B for when the "Magenta Line" tries to lead you into a swamp.