Living in California is a bit of a psychological trade-off. You get the world-class surfing and the Sierra Nevada peaks, sure, but you also live with the constant, low-level buzz of tectonic anxiety. Most people here have looked at a fault lines california map at some point, usually right after a 4.2 jolt makes the windows rattle. They want to know if that red line on the screen goes directly under their kitchen table. Usually, it doesn't. But sometimes, it’s closer than you’d think.

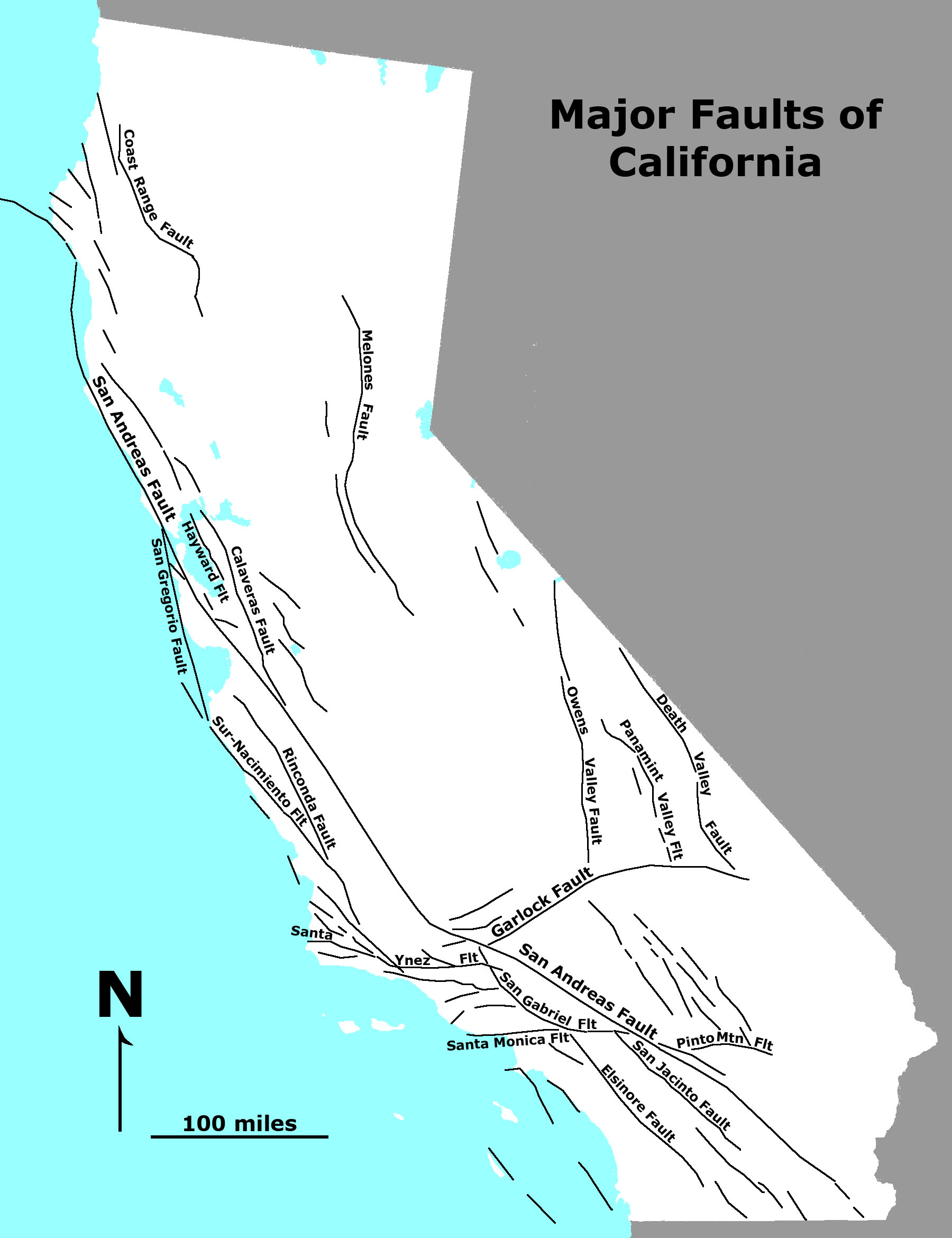

California isn't just sitting on one big crack in the earth. It’s more like a shattered windshield. There are hundreds of mapped faults, and likely thousands more that we haven't even found yet because they’re buried under miles of sediment or suburban sprawl.

The Big One and the Others We Forget

Everyone talks about the San Andreas. It’s the celebrity of faults. It runs roughly 800 miles through the state, acting as the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. If you're looking at a fault lines california map, it's that long, unmistakable scar cutting through the Carrizo Plain. But honestly? The San Andreas might not even be the one you should worry about most.

Take the Hayward Fault in the East Bay. It runs directly through Berkeley, Oakland, and Fremont. It passes right under the University of California, Berkeley’s football stadium. Geologists like Dr. Lucy Jones have pointed out for years that the Hayward is a "tectonic time bomb" because it’s so heavily urbanized. While the San Andreas can produce bigger quakes, a smaller rupture on the Hayward could do significantly more damage simply because of the sheer number of people living on top of it.

Then you have the blind thrust faults. These are the sneaky ones. They don't break the surface, so they don't show up as a visible line on the ground. The 1994 Northridge earthquake happened on one of these. Nobody knew it was there until the ground started moving. This is why a fault lines california map is a living document—it’s constantly being updated as new data from GPS sensors and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) comes in.

Understanding the Colors on the Map

When you open a map from the California Geological Survey (CGS) or the USGS, you’ll see different colors. Generally, these indicate the age of the last movement.

✨ Don't miss: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

- Holocene-Active: These are the scary ones. They’ve moved within the last 11,700 years. If a fault is Holocene-active, California law (the Alquist-Priolo Act) usually prohibits building new homes directly on top of it.

- Late Quaternary: These moved within the last 130,000 years. Less likely to go off tomorrow, but still technically active in geological time.

- Quaternary: Moved in the last 1.6 million years. Basically retired, but geologists never say never.

It's not just about the line. It's about the ground. You could be five miles away from a fault line and feel more shaking than someone standing right on it, depending on the soil. If you're on solid granite, you’ll shake. If you’re on "soft" soil or reclaimed land (like the Marina District in San Francisco), the ground can undergo liquefaction. Basically, the soil turns into quicksand. Not ideal for a foundation.

Why Your ZIP Code Matters More Than You Think

In 1972, California passed the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act. This was a game-changer. It basically said that if you want to build a house, you can't put it right on a known active fault trace. Most fault lines california map tools available to the public today are designed specifically to show these Alquist-Priolo zones.

If you're buying a house in California, you'll get a Natural Hazard Disclosure (NHD) report. It’ll tell you if you're in a zone. But here’s the kicker: these zones are only about 50 feet wide on either side of the fault. You could be 51 feet away and technically be "out of the zone," even though your neighbor's house is sitting on the line.

Does it matter? Sorta. Modern California building codes are incredibly rigorous. A well-built wood-frame house is designed to flex. It might get thrashed in a big quake, but it’s unlikely to collapse on you. The real danger usually comes from unreinforced masonry—think old brick buildings in downtown areas—or "soft-story" apartments where the first floor is mostly garage space with thin supports.

The Weird Geography of the San Andreas

Most people think the San Andreas is a straight line. It isn't. It has "bends." Near Los Angeles, there’s a "Big Bend" where the fault turns more east-west. This causes the two plates to smash into each other rather than just sliding past. This "smashing" is exactly why we have the San Gabriel Mountains. Every time there’s a big quake in that area, the mountains get a few inches taller.

🔗 Read more: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Southern California is a mess of faults. You have the Garlock Fault, which runs perpendicular to the San Andreas. You have the Newport-Inglewood fault, which runs right through densely populated parts of Long Beach and the Westside. When you look at a fault lines california map of the LA Basin, it looks like a plate of spaghetti.

Up north, the San Andreas heads out to sea near Point Arena but stays close to the coast. The 1906 San Francisco quake saw the ground shift up to 20 feet in some places. Imagine a fence line suddenly having a 20-foot gap in the middle. That’s the kind of power we’re talking about.

Modern Mapping Technology

We aren't just guessing anymore. Scientists use Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR). These are satellites that can detect ground movement as small as a few millimeters. They can literally see the crust "loading up" with tension like a giant spring being pulled back.

We can also look at the "creep." Some faults, like the segments of the San Andreas near Hollister, are "creeping" faults. They slide slowly and constantly. This is actually good news. It means the energy is being released in tiny bits rather than building up for one massive snap. If you visit Hollister, you can see sidewalks and curbs that are slowly being offset by the fault's movement. It’s a slow-motion car crash that’s been happening for decades.

How to Use a Fault Map Without Panicking

It’s easy to get overwhelmed. You see a red line near your kid's school or your office and you want to move to Idaho. But Idaho has quakes too. Most of the Western US does.

💡 You might also like: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

The goal of checking a fault lines california map shouldn't be to find a place with zero risk—that doesn't exist in California. The goal is risk mitigation.

- Check for Liquefaction Zones: These are often more dangerous than the fault line itself. If your house is on old marshland or fill, you need to know if the foundation is retrofitted.

- Look for Landslide Zones: If you live in the hills (think Malibu or the Oakland Hills), the shaking can trigger massive landslides.

- Retrofit Your Home: If your house was built before 1980, it might not be bolted to its foundation. This is a relatively cheap fix that prevents the house from literally sliding off its base during a quake.

- Secure Your Stuff: Most injuries in earthquakes aren't caused by collapsing buildings. They’re caused by flying bookshelves, TVs, and kitchen cabinets.

Realistically, the "Big One" is a statistical certainty, but the "When" is a total mystery. We might have another 50 years of quiet, or it could happen before you finish reading this. The USGS "Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast" (UCERF3) estimates a 99% chance of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake in California within the next 30 years. That’s not a scare tactic; it’s just the cost of doing business in paradise.

Practical Steps for Californians

If you’ve spent any time looking at a fault lines california map, you’re already ahead of the curve. Awareness is the first step. But don't stop at just looking at the lines.

Go to the California Earthquake Authority (CEA) website. They have tools that show you exactly what kind of retrofitting your specific type of home needs. If you’re a renter, ask your landlord if the building has been seismically retrofitted. Many cities, like Los Angeles and San Francisco, now mandate that "soft-story" buildings be fixed.

Next, download the MyShake app. It’s developed by UC Berkeley and uses your phone’s accelerometer to detect the initial P-waves of a quake. It can give you a few seconds of warning before the heavy S-waves (the ones that do the damage) arrive. A few seconds sounds like nothing, but it’s enough time to drop, cover, and hold on, or for a surgeon to pull a scalpel away, or for a train to start braking.

Finally, stop treating your "earthquake kit" like a secondary priority. You need a gallon of water per person per day for at least three days. Realistically? Aim for two weeks. If a major fault on that map ruptures, the infrastructure—water pipes, electricity, gas lines—will be down for a while. Being prepared means you aren't a burden on emergency services that will be stretched thin.

The map isn't there to scare you. It’s a blueprint for living smartly in a place that is literally moving under your feet. Accept the geology, prepare for the physics, and then go enjoy the sunshine.