Biology class is a trip. One minute you're looking at a blurry slide of onion skin, and the next, you're expected to memorize the intricate dance of ions moving across a phospholipid bilayer. It’s a lot. Most students end up staring at a blank diagram of a cell membrane, feeling like they've hit a brick wall. You’re likely here because you need a cell transport worksheet answer key to check your work or finally understand why that specific salt solution made the "cell" in your lab shrivel up like a raisin.

Let’s be real: biology isn't just about memorizing terms; it's about visualizing a tiny, chaotic world where everything is trying to reach a state of "chill" or equilibrium. If you’re stuck on a worksheet, you’re usually stuck on one of three things: the direction of flow, whether energy is required, or the specific protein involved. It's not just about getting the right letters in the blanks. It’s about the mechanics of life.

Why the Cell Membrane is Basically a Bouncer

Think of the cell membrane as a very picky bouncer at an exclusive club. It’s "selectively permeable." This means it doesn't just let anyone in. Small, uncharged molecules like oxygen can slip right through the front door without a second glance. This is simple diffusion. But if you're a big molecule or you've got an electrical charge—like a sodium ion—the bouncer is going to stop you.

You need a special pass.

When you're looking at your cell transport worksheet answer key, you'll see a lot of emphasis on the "phospholipid bilayer." These are those little matchstick-looking things with heads and tails. The heads love water (hydrophilic), and the tails absolutely hate it (hydrophobic). This creates a fatty barrier that most things can’t cross easily. This isn't just a design choice; it's a survival mechanism. If the membrane let everything in, the cell would pop or starve in minutes.

✨ Don't miss: JBL Tune Buds: Why These Mid-Range Buds are Actually Better Than Pro Models for Most People

Passive Transport: Going With the Flow

Passive transport is the easiest concept to grasp because it requires zero energy. No ATP. No effort. It’s like rolling a ball down a hill. Molecules naturally want to move from where there’s a lot of them (high concentration) to where there’s less of them (low concentration). This is the "concentration gradient."

There are three main types you'll find on any standard worksheet:

Simple Diffusion

This is for the tiny stuff. Oxygen and carbon dioxide just drift across the membrane. No help needed. If your worksheet asks about "gas exchange in the lungs," the answer is almost always simple diffusion.

Facilitated Diffusion

This is where people get tripped up. It’s still passive. It still goes from high to low. But the molecules are too big or too "weird" to go through the lipids. They need a "tunnel" or a "carrier." These are transport proteins. Imagine a bridge over a river; you're still walking across it yourself, but you couldn't cross the water without the bridge.

Osmosis

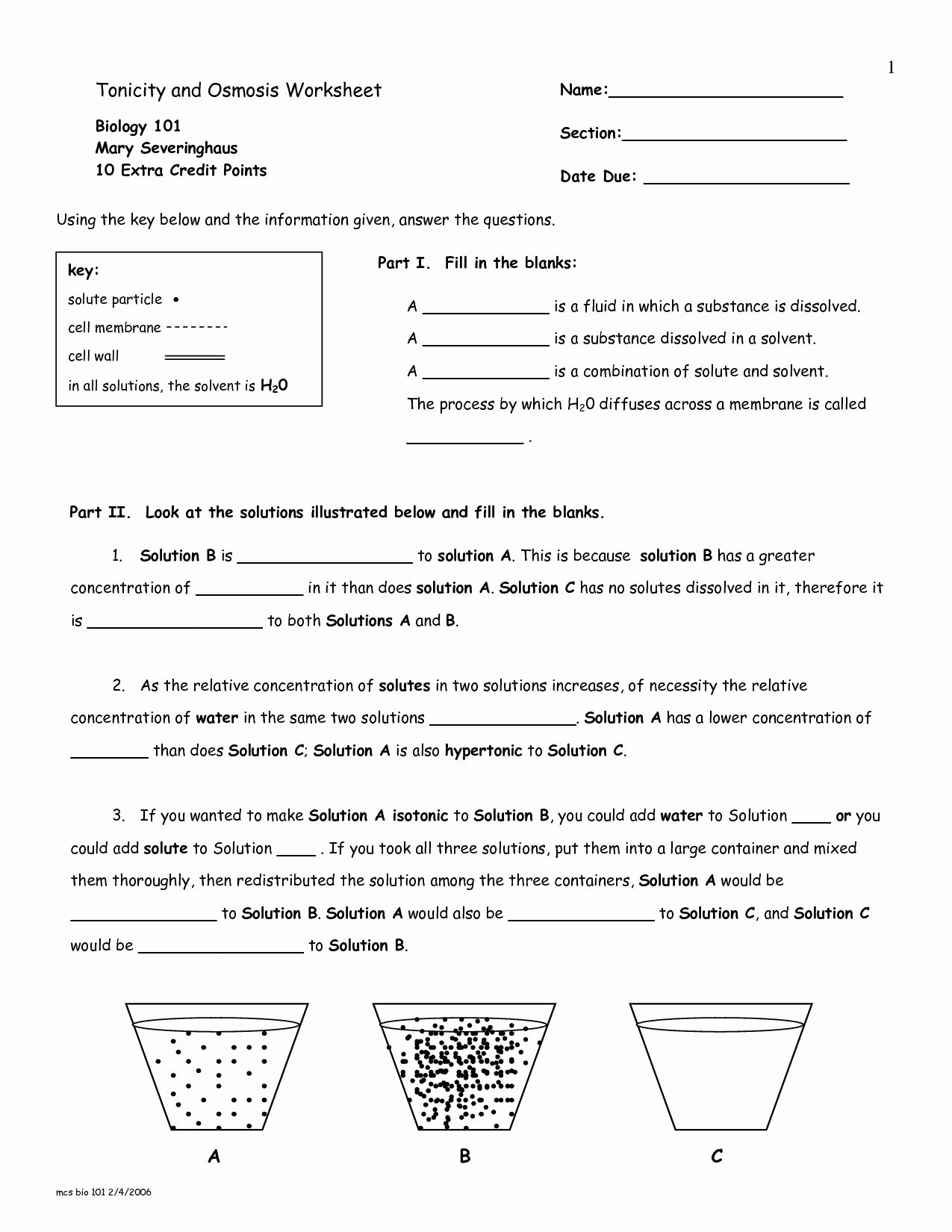

Osmosis is just a fancy word for the diffusion of water. But biology teachers love to make this complicated by using terms like hypertonic, hypotonic, and isotonic.

Honestly? Just remember this: Salt sucks. Wherever the salt (or solute) is higher, the water is going to go there to try and water it down. If you put a cell in a "hypertonic" solution (lots of salt outside), the water leaves the cell to go hang out with the salt. The cell shrivels. If the solution is "hypotonic" (low salt outside, high salt inside), water rushes into the cell. It might even explode. That’s called lysis.

Active Transport: The Upgradable Struggle

Sometimes a cell needs to move stuff against the gradient. It needs to cram more stuff into an already crowded room. This requires energy in the form of ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate). On your cell transport worksheet answer key, look for anything moving from "low to high" concentration. That’s a dead giveaway for active transport.

The most famous example is the Sodium-Potassium Pump. This thing is a workhorse. It spends about a third of your body's total energy just moving these two ions around. It pumps three sodium ions out and pulls two potassium ions in. Why? To keep your nerves firing and your muscles moving. Without this constant "pumping" against the gradient, your nervous system would basically shut down.

Bulk Transport: For the Truly Big Stuff

What happens when the cell needs to eat something huge, like a whole bacterium? It can't use a tiny protein channel. It uses bulk transport.

👉 See also: Apollo 13: What Really Happened During NASA’s Most Famous Failure

- Endocytosis: The membrane wraps around the object and pinches off to form a little bubble called a vesicle. Phagocytosis is "cell eating" (solids), and pinocytosis is "cell drinking" (liquids).

- Exocytosis: This is the reverse. The cell barfs out waste or sends out proteins it manufactured. The vesicle fuses with the membrane and spits the contents into the outside world.

If you see a diagram on your worksheet that looks like the cell membrane is "reaching out" to grab something, you’re looking at endocytosis.

Common Pitfalls on Worksheets

I’ve seen thousands of these worksheets. Students consistently miss the same three things. First, they confuse facilitated diffusion with active transport because both use proteins. Look at the arrow. Is it going from high to low? It’s facilitated diffusion. Low to high? Active transport.

Second, the "water potential" trick. Sometimes worksheets won't talk about "solute concentration"; they’ll talk about water potential. It’s the same thing, just inverted. High water potential means lots of water (low salt). Low water potential means little water (high salt).

Third, the "dynamic equilibrium" trap. Just because a cell has reached equilibrium doesn't mean the molecules stop moving. They still move back and forth! They just do it at the same rate, so there’s no net change. If an answer key asks if movement stops at equilibrium, the answer is a hard "No."

How to Actually Use an Answer Key Correctly

Using a cell transport worksheet answer key to just copy-paste is a waste of your time. You’ll fail the unit test. Instead, use the key to reverse-engineer the logic. If the answer says "Hypertonic," look at the diagram and find where the dots (solutes) are most crowded.

🔗 Read more: Why Pics of Past PC Cases Still Make Us Weirdly Nostalgic

Verify the source of your key. Many online resources like Quizlet, Course Hero, or Biology Corner have great materials, but they also have user-generated errors. Cross-reference the answer with your textbook’s definition of the fluid mosaic model.

Take Actionable Steps to Master Cell Transport:

- Draw the Gradient: On every worksheet problem, draw a big arrow from the "crowded" side to the "empty" side. This tells you where the stuff wants to go.

- Identify the Energy: Check if the problem mentions ATP. If it does, you're in Active Transport territory immediately.

- The "Salt Sucks" Rule: Apply this to every osmosis question. Find the saltier side; the water is moving that way.

- Vocab Check: Make sure you can explain the difference between a "protein channel" (a tunnel) and a "carrier protein" (which changes shape).

- Test with Scenarios: Ask yourself, "What happens to a freshwater fish in the ocean?" (It’s in a hypertonic environment, so it loses water and dies). Applying it to real life makes it stick.

Once you stop seeing these as just words on a page and start seeing them as the literal physics of your body, the answers start to feel obvious. Grab your worksheet, find the patterns, and don't let the terminology intimidate you. You've got this.