Mars is a freezing, radiation-blasted desert. It’s basically a rusted ball of rock hanging in the void. Yet, for decades, we’ve been obsessed with finding water on Mars because, honestly, without it, our dreams of being a multi-planetary species are dead on arrival. We aren't just looking for a few damp rocks anymore. We are looking for the fuel, the oxygen, and the literal lifeblood of future colonies.

It’s there. We know it’s there. But finding water on Mars isn't like digging a well in your backyard. It's a complex, frustrating scavenger hunt across a planet that wants to kill you.

👉 See also: Experian Credit Score App: What Most People Get Wrong About Raising Their Score

The Great Martian Drying

Billions of years ago, Mars was blue. We see the scars everywhere—ancient river valleys, massive deltas like Jezero Crater where the Perseverance rover is currently poking around, and shorelines that suggest a northern ocean once covered a third of the planet. But Mars lost its magnetic field. Without that shield, the solar wind stripped away the atmosphere, and the water either escaped into space or retreated underground.

Today, the atmospheric pressure is so low that liquid water can't really exist on the surface. It would either freeze instantly or boil away—a process called sublimation. If you stood on the Martian equator at noon, your feet might be at a comfortable 20°C while your head is freezing at 0°C. That weird instability makes the hunt for liquid water a nightmare.

How we actually go about finding water on Mars

NASA doesn't just look for "wet spots." They use a suite of high-tech tools that feel like something out of a sci-fi novel. One of the most successful methods involves the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and its SHARAD (Shallow Radar) instrument. It beams radar waves into the ground and listens for the echo. Different materials reflect waves differently. Massive deposits of subsurface ice have been mapped this way, particularly in regions like Utopia Planitia.

Then there’s the Phoenix lander. Back in 2008, it literally scraped the dirt in the northern polar region and found bright white patches. A few days later? The patches were gone. They had sublimated. That was a "eureka" moment—solid proof of water ice just inches below the dust.

We also use neutron spectrometers. These instruments detect hydrogen. Since water is $H_2O$, a massive spike in hydrogen usually points to water molecules trapped in the soil or buried ice sheets. This is how the Odyssey orbiter found that Mars is actually quite "wet" if you look just beneath the surface.

The controversy of RSLs

You might remember the 2015 headlines about "Liquid Water Confirmed on Mars." Those were based on Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL)—dark streaks that appear on crater walls during warm seasons. People thought it was salty brine seeping out.

But science is rarely that simple.

📖 Related: How to view deleted messages on Instagram: What actually works in 2026

Later studies suggested these might just be dry grain flows—basically sand avalanches. The debate is still heated. Some researchers, like those working with the HiRISE camera data, argue that the lack of a clear water signature in some RSL sites means we shouldn't get our hopes up for flowing streams just yet. It’s a classic example of how finding water on Mars involves a lot of "maybe" before we get to a "definitely."

Where the "Gold Mines" are hidden

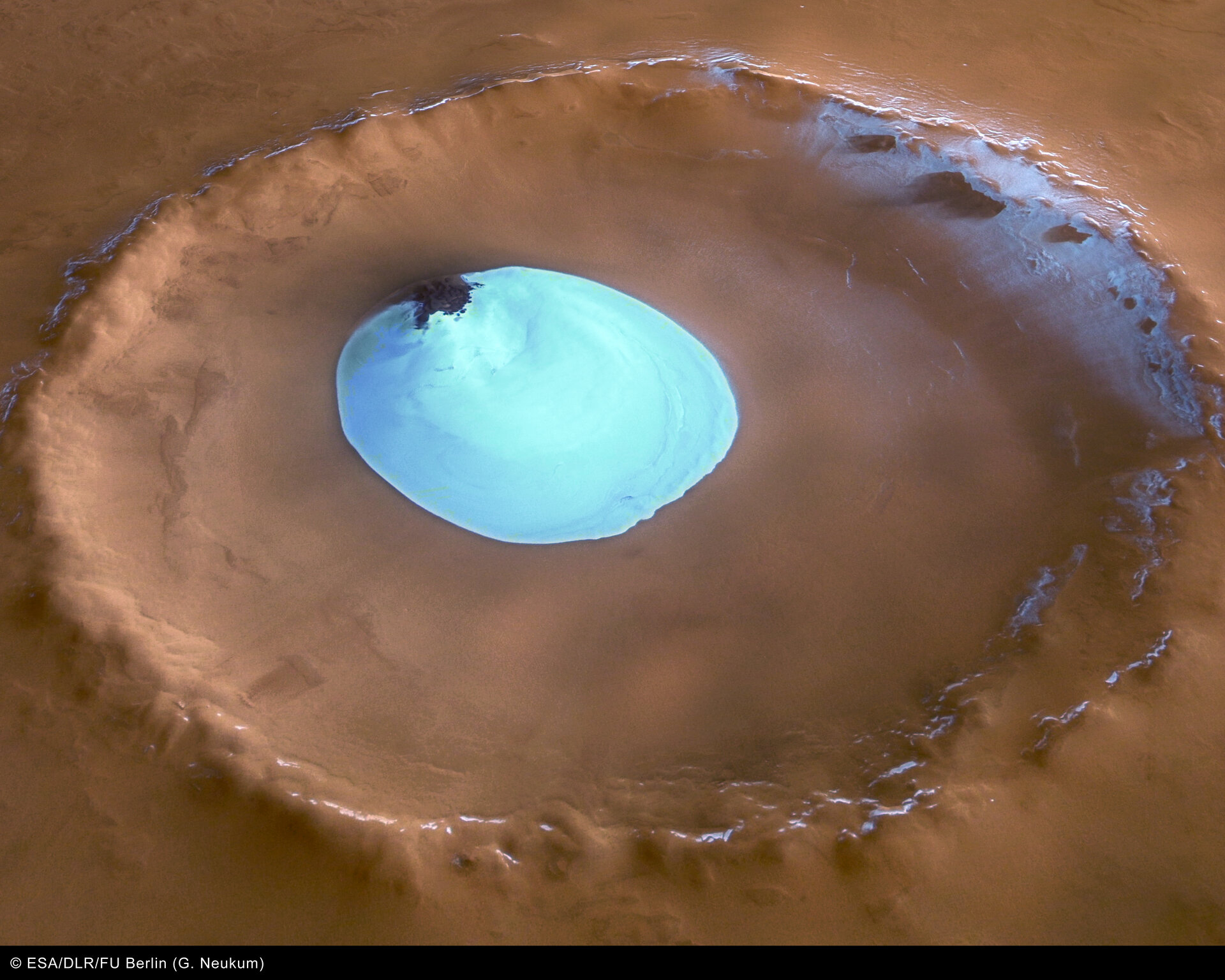

If you want to find the motherlode, you go to the poles. The Martian polar caps are massive. The north pole is mostly water ice, while the south pole is a sandwich of water ice and dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide). If you melted the south polar cap, you’d cover the entire planet in 11 meters of water.

But we can't live at the poles. It’s too cold, and the seasonal darkness is a power nightmare for solar panels.

The real prize is mid-latitude ice.

Recent data from the Mars Express orbiter suggests there are "dust-covered glaciers" near the equator. These are massive slabs of ice protected from the sun by a thick layer of Martian regolith (dirt). For a future SpaceX Starship crew, this is the jackpot. You don't need to melt a pole; you just need to dig.

The problem with "Ghost Water" and Subglacial Lakes

In 2018, the MARSIS radar found what looked like a massive liquid lake 1.5 kilometers under the ice at the south pole. It was huge—20 kilometers wide.

But wait.

For water to be liquid at those temperatures, it would need to be incredibly salty—basically a toxic sludge of perchlorates—or there would need to be a local heat source like a magma chamber. Many scientists are now skeptical. They suggest the "shiny" radar reflections might actually be volcanic rock or clays like smectites.

Finding water on Mars often feels like chasing a mirage. What looks like a lake on a computer screen might just be a specific type of frozen mud. We won't know for sure until we put a drill through it.

Why perchlorates change everything

Martian soil is full of perchlorates. These are salts that are pretty toxic to humans, but they act like antifreeze for water. They lower the freezing point significantly. This means that even in the brutal Martian cold, "brines" could theoretically exist as a liquid film between soil grains.

This is a double-edged sword.

- It means liquid water is more likely than we thought.

- It means that water is probably "salty" enough to kill a human if they drank it without massive desalination efforts.

The Biological "No-Go" Zones

There is a weird catch to finding water on Mars. If we find a place that is actually wet and warm, we might not be allowed to go there. NASA has "Planetary Protection" protocols. If a spot is "habitable," we don't want to accidentally contaminate it with Earth bacteria hitchhiking on our rovers.

Imagine finding life on Mars, only to realize it's just E. coli that fell off a lug nut from the 2020 mission. That would be a scientific disaster of historic proportions.

Mining the sky

We aren't just looking in the ground. The Martian atmosphere has humidity. It’s tiny—about 0.03%—but it’s there. There are designs for "atmospheric water harvesters" that could basically squeeze water out of the thin air. It’s much less efficient than mining ice, but it’s a great backup plan for a colony.

The Practical Path Forward

So, where does this leave us? We've moved past the "is there water?" phase. Now we are in the "how do we get it?" phase.

✨ Don't miss: Instagram Won't Send Code to Phone: Why It Happens and How to Fix It

If you are following the progress of Mars exploration, keep an eye on these specific developments:

- Vertical Mapping: We need higher resolution radar to find ice that is within 1-2 meters of the surface. This is the "sweet spot" for human mining.

- The Mars Ice Mapper Mission: A proposed mission specifically designed to find accessible ice for human missions. This is the bridge between "science" and "colonization."

- In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): This is the tech that will turn Martian ice into rocket fuel ($CH_4$) and breathable oxygen ($O_2$).

Finding water on Mars is no longer just a quest for signs of ancient life. It’s a logistical necessity. We’ve confirmed the ice is there in staggering quantities. The next decade will be about proving we can reach it, purify it, and use it to survive on a world that offers no second chances.

Actionable insights for the space-curious

If you want to stay ahead of the curve on this topic, don't just read the general news. Follow the HiRISE image releases from the University of Arizona; they often post raw photos of new impact craters that have un-earthed fresh ice. Also, look into the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) results. While it focused on oxygen, the lessons learned about handling Martian dust and atmosphere are directly applicable to future water-mining rigs.

The "Red Planet" is actually a very "White Planet" just beneath the surface. We just need to start digging.

---