You’ve probably seen the headlines. Every few years, a grainy, rust-colored photo makes the rounds on social media, claiming to be the "smoking gun" for life on the Red Planet. Honestly, looking at a water on Mars real image for the first time can be a bit of a letdown if you’re expecting rushing rivers or deep blue crystalline lakes. It isn't like Earth.

Mars is a desert. It is a freezing, thin-aired, radiation-soaked wasteland where liquid water shouldn't really exist on the surface at all. Yet, if you look at the right data from NASA’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) or the Perseverance rover’s Mastcam-Z, you see things that shouldn't be there. Streaks. Frost. Ice tucked away in the shadows of craters like a secret.

The story of Martian water is less about "finding a lake" and more about detective work involving chemistry, temperature, and some very high-tech cameras.

The Famous RSL Streaks: Liquid or Just Dust?

For a long time, the holy grail of Martian photography was the Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL). These are dark, narrow streaks that appear on steep slopes during warm seasons and then fade away when it gets cold. When we first saw a water on Mars real image featuring these streaks, the scientific community went wild. It looked like water was seeping out of the ground.

Lujendra Ojha, a researcher who originally spotted these while at the University of Arizona, helped identify chemical signatures of hydrated salts in these areas. This suggested that "brines"—basically super-salty water—might be flowing. Salt lowers the freezing point of water, which is how it could stay liquid in the brutal Martian cold.

But science is messy.

Later studies, including those published in Nature Geoscience, suggested these might actually be "dry" granular flows. Basically, very sophisticated landslides of sand. It was a bummer for those of us hoping for Martian streams, but it highlights how hard it is to interpret a photo taken from miles above the surface. We are looking at shadows and contrast, trying to figure out if we’re seeing a wet spot or just a different shade of dirt.

📖 Related: What Does su Stand For? The Command That Actually Runs the Internet

Real Ice in the Korolev Crater

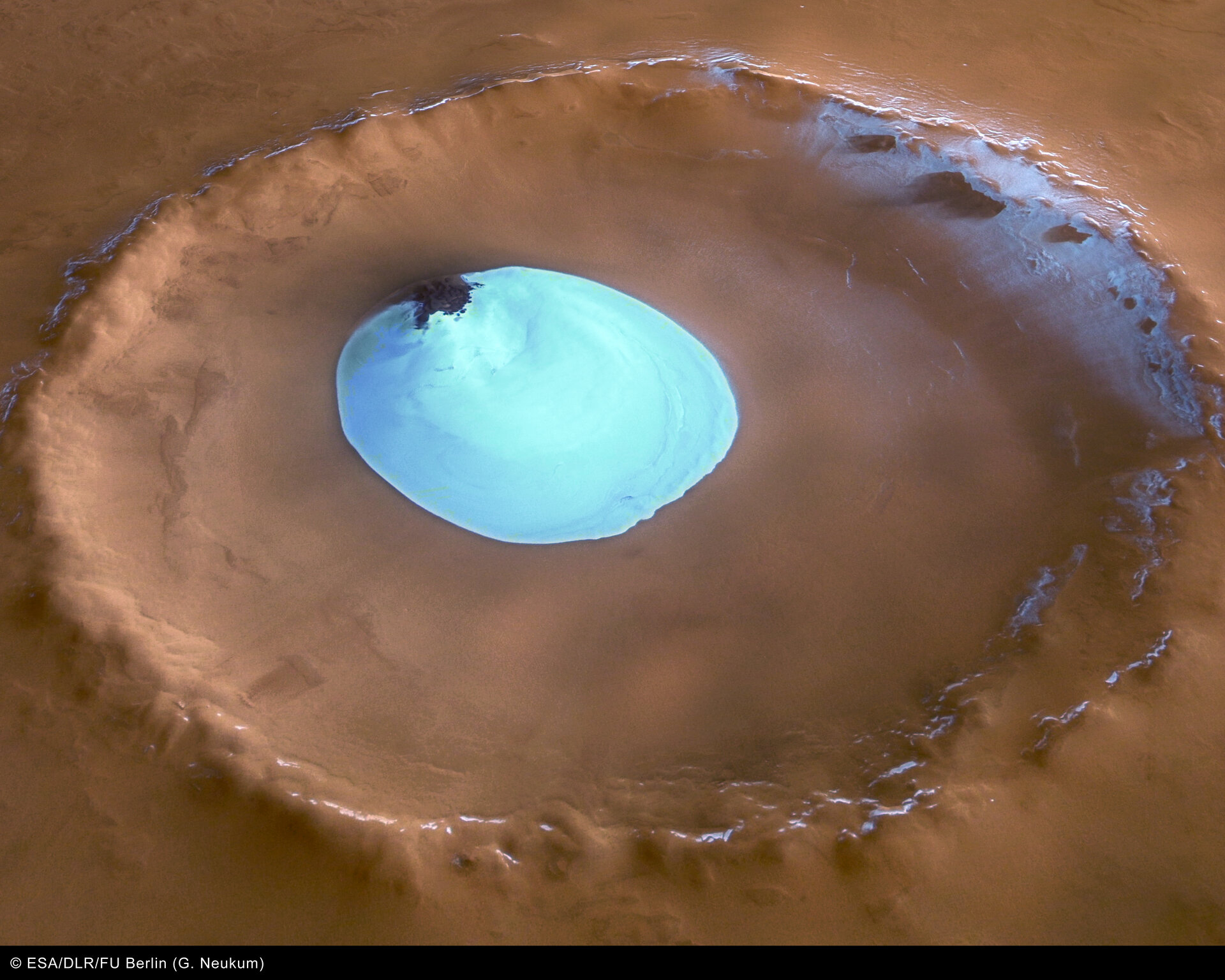

If you want a water on Mars real image that actually looks like what you’d imagine, you have to look at the Korolev Crater. This is a 50-mile-wide massive bowl near the north pole. It’s filled with a permanent mound of water ice about a mile thick.

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express mission captured this in stunning detail. It looks like a giant skating rink. Because the crater acts as a "cold trap," the air moving over the ice cools down, sinks, and creates a protective layer of cold air that keeps the ice from melting or sublimating into gas. It’s a literal reservoir of frozen water sitting right there in the open.

This isn't just a "maybe." It's a massive, undeniable block of H2O. If we ever send humans to Mars, places like Korolev are the gas stations of the future.

Why can't we just see the liquid?

Physics is the jerk in this scenario. The Martian atmosphere is roughly 1% as thick as Earth's. If you stood on Mars with a cup of liquid water, it would do two things simultaneously: freeze and boil. The low pressure means the boiling point drops drastically.

Unless that water is incredibly salty, it won't stay liquid for more than a few seconds. That’s why we see "geomorphological evidence"—a fancy way of saying "shapes in the dirt"—rather than actual puddles. We see gullies. We see deltas. We see dried-up riverbeds that look exactly like the ones in the Australian outback or the Atacama desert.

The Perseverance Rover and the Jezero Delta

Right now, the Perseverance rover is crawling through an area called Jezero Crater. Billions of years ago, this was a lake fed by a river. The water on Mars real image files coming back from "Percy" show incredibly clear sedimentary layers.

You can see the way rocks are stacked. On Earth, that only happens when a steady flow of water carries silt and drops it over thousands of years. Dr. Katie Stack Morgan and the team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have pointed out specific boulders that seem to have been moved by high-energy floods.

🔗 Read more: Ask Jeeves a Question: Why We Still Miss the Internet’s Most Famous Butler

It’s a ghost story written in stone.

The images show "cross-bedding," where layers of sand are tilted. It’s the kind of thing a geology student would recognize in a heartbeat at a local creek. On Mars, it's proof that the planet used to be "blue," or at least "muddy."

Is there water underground?

This is where things get controversial. In 2018, the MARSIS radar instrument on the Mars Express orbiter detected a massive reflection under the ice of the southern polar cap. Many scientists argued this was a subglacial lake, similar to Lake Vostok in Antarctica.

If true, it would be the biggest discovery in the history of space exploration.

However, other experts, like those using data from the South China University of Technology, have argued that these reflections could just be certain types of clay or volcanic rock that look "bright" to radar. We don't have a water on Mars real image of this lake because it's buried under miles of ice. We only have "pings" and graphs. It’s a debate that won’t be settled until we send a drill.

How to Spot a Fake vs. a Real Image

The internet is full of "re-colored" images that make Mars look like a lush paradise. If you see a photo where the sky is bright blue and the water is shimmering turquoise, it’s probably a render or an "enhanced color" image used for artistic purposes.

- Check the Source: Look for the NASA, ESA, or CNSA (China National Space Administration) watermark.

- Raw Data: NASA actually publishes the raw images from the rovers daily. They are usually black and white or have a weird yellow tint because the cameras use specific filters to see through dust.

- True Color vs. False Color: Scientists often use "false color" to highlight different minerals. In these images, water ice might look bright blue or purple to make it stand out against the red soil. It doesn't mean the ice is actually neon blue.

Honestly, the real images are cooler because they show how alien the environment is. Seeing white carbon dioxide frost on the rim of a crater is a reminder that we are looking at a world that follows different rules than ours.

Actionable Insights for Mars Enthusiasts

If you want to track the hunt for water yourself, don't just wait for the news. You can go straight to the source.

- Browse the HiRISE Catalog: This is the most powerful camera ever sent to another planet. You can search their database for "gullies" or "ice" to see the highest-resolution water on Mars real image files available.

- Follow the Raw Feeds: The Mars 2020 mission (Perseverance) has a public gallery where every single photo taken by the rover is uploaded within hours. Look for the "Delta" images to see where the water used to be.

- Use Google Mars: Just like Google Earth, you can toggle a "water" layer in some interactive maps to see where historical evidence of flooding is most prominent.

- Distinguish Between CO2 and H2O: Remember that the white stuff at the poles is a mix. The "seasonal" caps are mostly dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide), while the "permanent" caps contain the actual water ice.

The evidence is all around us. Mars was once a world of oceans, and today, that water is still there—hiding in the rocks, frozen in the craters, and perhaps flowing in salty streaks just out of reach of our current landing sites.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Download the NASA Eyes on the Solar System app. It lets you fly alongside the orbiters in real-time.

- Check the University of Arizona's HiRISE website for the "Image of the Day," which often features detailed analysis of new water-related geological formations.

- Read the actual white papers on RSL (Recurring Slope Lineae) if you want to understand why scientists are still arguing about whether those dark streaks are wet or dry.

The search isn't over. We are basically waiting for a rover to get lucky enough to stumble onto a patch of morning frost or a damp cave entrance. Until then, we have the stones and the ice to tell the story.