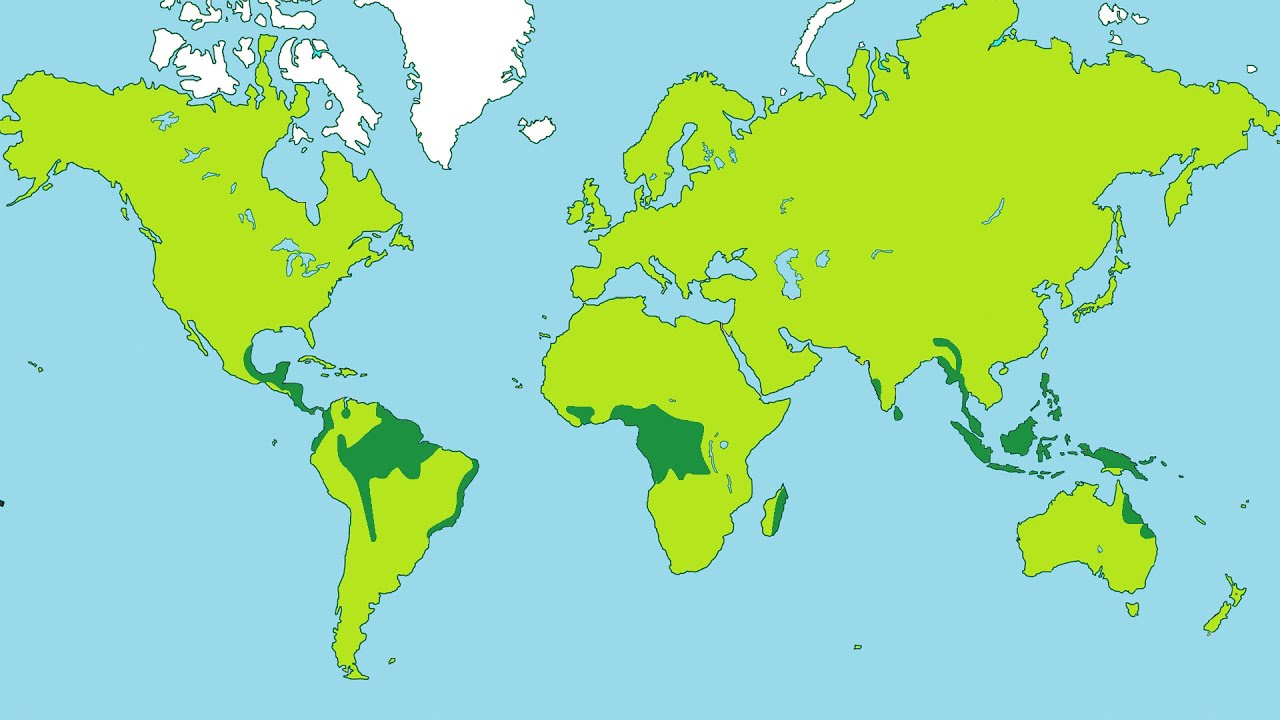

Look at a globe. Spin it. If you focus on the middle, right around the equator, you'll see a jagged, broken ribbon of deep green. That's it. That is the tropical rainforest in the world map, a thin biological skin that manages to house more than half of the world’s plant and animal species despite covering less than 6% of Earth’s land surface. It’s a bit mind-blowing when you actually think about the density.

Rainforests aren't just "woods." They are vertical cities.

Most people think of the Amazon. And yeah, it’s the big one. But if you look closer at the map, you’ll notice these forests are strictly "tropic" for a reason. They live in the Frost-Free Zone. Basically, if the temperature drops below freezing, the system breaks. They sit between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, hugging the equator like a warm, wet scarf.

Where the Green Actually Sits

If you're trying to locate a tropical rainforest in the world map, you have to look at three specific regions. First, the Americas. The Amazon Basin is the heavyweight champion here, stretching across nine nations, with Brazil holding the lion's share. But don't overlook the Atlantic Forest or the Chocó-Darién.

Then you’ve got Africa. The Congo Basin is the "second lung" of the planet. It’s darker, denser, and often more overlooked than the Amazon.

Finally, there’s Southeast Asia and Oceania. This is the fragmented part of the map. It’s a collection of islands—Borneo, Sumatra, New Guinea—and the Malay Peninsula. These areas are unique because they aren't one continuous landmass. They are evolutionary laboratories separated by water.

The Latitudinal Lock

Why there? Why not in Europe or the central US?

🔗 Read more: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

It’s about the Sun. Near the equator, the sun hits at a direct angle almost all year. This creates intense heat, which evaporates water, which then rises, cools, and dumps back down as rain. It’s a closed-loop system. You get about 80 to 400 inches of rain a year. Honestly, it’s more like living in a giant, lukewarm shower than a forest.

The Three Big Players on the Map

1. The Amazon (The Giant)

It spans 2.1 million square miles. If the Amazon were a country, it would be the ninth largest in the world. It’s huge. But it’s also under massive pressure. When you look at satellite imagery of the tropical rainforest in the world map, you can see the "fishbone" patterns of deforestation. Roads go in, and then small ribs of clearing fan out. It’s changing the local climate. Scientists like Carlos Nobre have warned that we are approaching a "tipping point" where the Amazon might stop making its own rain and turn into a dry savanna.

2. The Congo Basin (The Carbon Sink)

This is Africa’s green heart. It’s arguably more resilient than the Amazon because it’s harder to access, but that’s changing. It stores incredible amounts of carbon in its peatlands. If you wiped the Congo off the map, the global temperature would spike almost instantly. It’s home to forest elephants and lowland gorillas, creatures that literally shape the physical structure of the jungle by trampling undergrowth and dispersing seeds.

3. Southeast Asia (The Fragile Archipelago)

This is where the map gets messy. These forests are the most threatened. Between palm oil plantations in Indonesia and logging in Malaysia, the green patches on the map are flickering out. This region is home to the Orangutan, a creature that exists nowhere else. Because these forests are on islands, once a patch is gone, the species inside it have nowhere to run. They can't just migrate a hundred miles north.

Why the Map is Lying to You

Maps are static. The tropical rainforest in the world map you see in a 2010 textbook is a lie today.

We are losing about 10 million hectares a year. To put that in perspective, imagine losing an area the size of South Korea every single year. When you look at a map, you see a solid block of green. In reality, it’s often "fragmented."

💡 You might also like: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

Fragmentation is a silent killer.

When you cut a road through a forest, you create "edges." These edges are hotter, drier, and windier than the deep interior. The specialist species—the ones that need the deep, dark damp—die off. You’re left with a "forest" that looks green from a satellite but is biologically hollow on the ground. It's called "Empty Forest Syndrome."

The Layers You Can't See on a Map

A 2D map doesn't show you the height. A tropical rainforest is a 3D grid.

- The Emergent Layer: These are the giants, the trees that poke out above the canopy like skyscrapers. They deal with the full force of the wind and sun.

- The Canopy: This is the roof. About 70-90% of the forest's life happens here. It’s a thick layer of leaves and branches that blocks out most of the sunlight.

- The Understory: It’s dark here. Plants have huge leaves to catch what little light filters down.

- The Forest Floor: Surprisingly, it’s not covered in thick grass. It’s mostly decaying leaves and fungi. Because the heat and moisture are so high, things rot fast. A fallen leaf disappears in weeks, whereas in a temperate forest, it might take a year.

Real-World Consequences of the Shrinking Map

This isn't just about "saving the trees" because they look nice. It’s about water.

Rainforests act as "biotic pumps." They pull moisture from the ocean and pump it into the interior of continents. The soy farmers in Brazil and the corn farmers in the US Midwest actually rely on the moisture regulated by these forests. If the green on the map disappears, the rain stops falling thousands of miles away.

Then there’s the medicine aspect.

📖 Related: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

Roughly 25% of modern medicines originate from rainforest plants. Yet, we’ve screened less than 1% of them for medicinal properties. We are essentially burning a library before we’ve even read the books. The rosy periwinkle from Madagascar, for instance, gave us a treatment for childhood leukemia. Imagine what’s in the parts of the map we’re currently clearing for cattle ranching.

How to Actually "Read" a Rainforest Map Today

If you want to understand the current state of the tropical rainforest in the world map, you need to look at "Global Forest Watch." It’s a near real-time satellite tracker.

You’ll see red dots. Those are fires.

You’ll see pink areas. That’s recent loss.

The "map" is a living, breathing entity that is currently gasping for air. While places like Costa Rica have actually managed to increase their forest cover through aggressive conservation and ecotourism, they are the exception. Most of the world’s rainforests are in developing nations where the choice is often between "protecting the trees" and "feeding the family."

It’s a complex, messy reality.

Actionable Steps for the Conscious Map-Watcher

You don't have to fly to Manaus to make a difference. The map is shaped by what we buy.

- Check your labels: If it contains palm oil, make sure it’s RSPO certified. Better yet, avoid it if the source is murky. Palm oil is a primary driver of deforestation in Southeast Asia.

- Beef origins: If you're buying cheap, mass-produced beef, there’s a high chance it was raised on land that used to be the Amazon. Look for local or grass-fed options with a traceable supply chain.

- Support Land Rights: Evidence shows that when Indigenous communities have legal titles to their land, deforestation rates plummet. Supporting organizations like Survival International or the Rainforest Foundation helps secure these rights.

- Use the Tech: Download the Global Forest Watch app. See for yourself where the changes are happening. Knowledge is the only way to stop the "green" on the map from becoming a historical footnote.

The tropical rainforest in the world map is the planet's most complex masterpiece. It took millions of years to build and only a few decades to fragment. Understanding where it is—and why it's disappearing—is the first step in making sure the map doesn't turn brown.