You’re standing on a street corner in Chicago or maybe a drafty platform in New York, and the local news says it’s 30 degrees. But your face feels like it’s being micro-planed by an ice-covered cheese grater. That’s because the thermometer is lying to you. Or, more accurately, it’s only telling you half the story. If you want to know how to find the wind chill, you have to stop looking at the red line on the glass and start looking at the physics of how your body actually leaks heat.

It’s cold. Seriously cold.

Most people think wind chill is a "real" temperature that exists in the air. It isn't. If you put a thermometer outside in a 40-mile-per-hour gale, it will read the exact same temperature as it would in a still room. The wind doesn't make the air colder; it just makes you colder by stripping away the thin layer of warm air your body works so hard to maintain against your skin. This is the "boundary layer." When the wind blows, it rips that layer away, forcing your body to heat a new batch of air. Do that fast enough, and your internal furnace simply can't keep up.

The Math Behind the Shiver

Back in 2001, the National Weather Service (NWS) and Meteorological Services of Canada decided the old way of calculating this stuff was, frankly, a bit rubbish. They updated the formula to be more "human-centric." They used clinical trials where people were put on treadmills in cold wind tunnels with sensors attached to their faces. It sounds like a mild form of torture, but it gave us the Wind Chill Temperature (WCT) index we use today.

💡 You might also like: European Street San Marco: Why This Jacksonville Classic Still Hits Different

The formula looks like a nightmare from a high school algebra final. If you really want to calculate it yourself, here is the beast:

$$WC = 35.74 + 0.6215T - 35.75(V^{0.16}) + 0.4275T(V^{0.16})$$

In this equation, $T$ is the air temperature in Fahrenheit and $V$ is the wind speed in miles per hour.

Nobody is doing that in their head while walking the dog. Basically, the math assumes you are walking at 3 mph (the average human pace) and that the wind is hitting your face at five feet above the ground. If you’re shorter, taller, or running, the numbers shift.

How to Find the Wind Chill Without a Calculator

Since most of us aren't carrying a scientific calculator or a desire to solve exponents in a blizzard, there are easier ways to get the number.

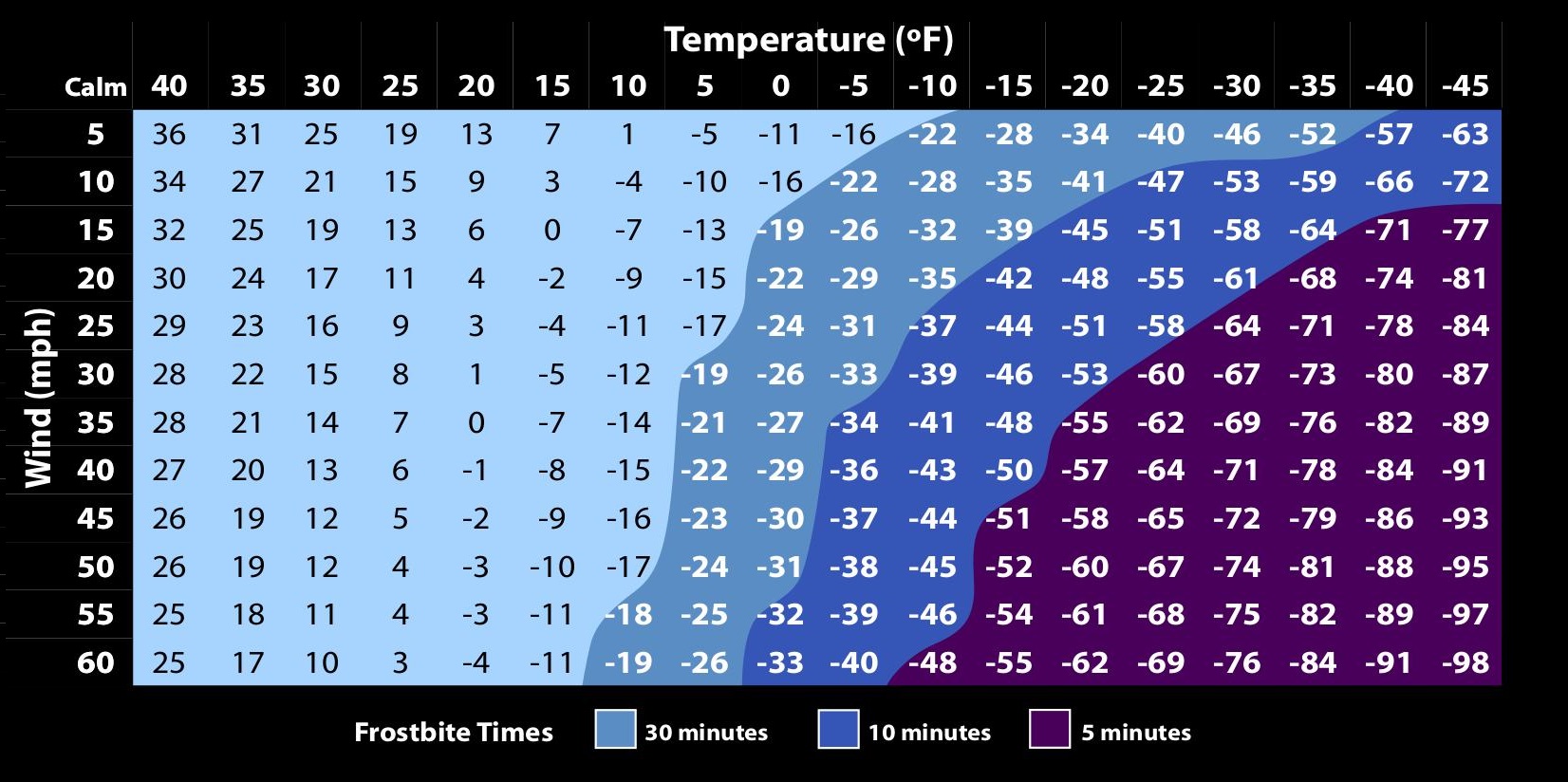

The easiest path? Use the NWS Wind Chill Chart. It’s a color-coded grid that cross-references temperature and wind speed. You find the temperature on the top, the wind speed on the left, and where they meet is your "feels like" number. It’s low-tech, but it’s what the pros use.

If you are out in the wild and need a quick estimate, you can use a "rule of thumb" method. For every 5 mph of wind, the temperature feels roughly 5 to 8 degrees colder, depending on how low the base temperature already is. This isn't perfect—physics is rarely that linear—but it keeps you from getting frostbite because you underestimated a gust.

Why Your Phone App Might Be Lying

Ever noticed how your iPhone says it's -5 but your car says it's 2 degrees? Apps often pull data from the nearest airport. If you’re in a "canyon" of skyscrapers or a sheltered valley, the wind speed at the airport might be totally different from where you are standing.

To get an accurate reading for your specific spot, you need two things:

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone in Johnson County is Obsessed With Five Below Overland Park

- A handheld anemometer (those little spinning fan gadgets).

- A standard digital thermometer.

Measure the wind speed right in front of your face. Then, check the actual air temp. If you have those two numbers, you can plug them into a wind chill app or the NWS online calculator to get the "true" chill for your exact location. Honestly, most people just guess, but if you’re ice fishing or winter hiking, guessing is how you lose a toe.

The Biological Reality of "Feels Like"

We talk about wind chill like it’s just a number, but it’s actually a safety warning. The index was specifically designed to predict how long it takes for human skin to freeze.

When the wind chill hits -18°F, you have about 30 minutes before frostbite sets in.

When it hits -33°F, you’re down to 10 minutes.

At -60°F? You’ve got five minutes.

It’s scary fast.

There's a common misconception that wind chill affects inanimate objects. It doesn’t. Your car’s radiator will never drop below the actual air temperature, no matter how hard the wind blows. However, the wind will make the radiator reach that air temperature much faster than it would in still air. It’s all about the rate of heat loss. This is why your house feels draftier on windy days even if the thermostat is set to 70; the wind is literally sucking the heat out of the building materials.

The Limitations of the Index

It is worth noting that the wind chill index has its critics. It doesn't account for sunshine. A bright, sunny day can make a -10 wind chill feel much more bearable because of solar radiation hitting your clothes. It also doesn't account for humidity (which is usually low in winter anyway) or what you’re wearing. If you're in a high-tech windbreaker, that "stripping of the boundary layer" doesn't happen nearly as effectively as it does if you're wearing a porous wool sweater.

Also, the index is based on the human face. It doesn't tell you how cold your feet feel or how fast your core temperature will drop if your torso isn't protected. It's a specific tool for a specific problem: exposed skin.

Step-by-Step for Real-World Accuracy

If you want to be precise about finding the wind chill today, follow this workflow:

- Check the local "ASOS" or "AWOS" station data. These are the high-end weather stations at airports. Most weather sites (like Weather Underground) allow you to see the "Current Conditions" from the closest station.

- Account for "Tunneling." If you are in an urban area, wind speeds can double between buildings (the Venturi effect). If the airport says 10 mph, it might be 20 mph on the street.

- Use the 2001 NWS Formula. If you’re a nerd, keep a bookmark of the NWS calculator on your phone’s home screen.

- Observe the "White Flag" markers. If you don't have a tool, look at flags or trees. A flag standing straight out usually indicates 25-30 mph winds. That’s a massive multiplier for heat loss.

Staying Alive in the Chill

Knowing how to find the wind chill is step one. Step two is actually respecting the number.

Layering is the only defense. You need a base layer to wick sweat (because being wet in a wind chill is a death sentence), a middle layer for insulation, and—most importantly—a shell that is 100% windproof. If air can move through your jacket, the wind chill wins.

🔗 Read more: How to Pronounce Schadenfreude Without Sounding Like a Total Amateur

Don't forget the nose. Since the wind chill index is literally calibrated based on facial skin, your nose and cheeks are the first things to go. A neck gaiter or a balaclava isn't just for skiers; it's a physiological barrier that maintains that warm air pocket the wind is trying to steal.

Practical Next Steps for Cold Weather Prep

- Download a "hyper-local" weather app: Apps like Carrot Weather or Dark Sky (now integrated into Apple Weather) use station aggregation to give you a better sense of wind speed in your specific neighborhood.

- Invest in a windproof outer shell: Look for materials like Gore-Tex or tightly woven nylon. If you can blow air through the fabric with your mouth, it won't protect you from wind chill.

- Check the "Frostbite Times": Always look at the NWS chart before heading out for more than 15 minutes in sub-zero temps. If the chart says 10 minutes to frostbite, do not leave your house without every inch of skin covered.

- Calibrate your car: Remember that your car's external temp gauge is usually accurate for air temperature, but it cannot calculate wind chill. You have to do that mental math yourself based on how fast you see the trees moving.