You’ve probably looked at the Thames river on map a thousand times and thought you knew exactly what was going on. It’s that blue wiggly line cutting through London, right? Sort of. But if you actually try to follow that blue line from its source to the sea, things get weirdly complicated very quickly. Most people just focus on the "London bit"—the part with the London Eye and the Tower Bridge—but that’s barely a fraction of the story.

The Thames isn't just a river; it's a 215-mile long contradiction. It starts in a quiet, often dry field in the Cotswolds and ends up as a massive, churning estuary that basically looks like the ocean. When you pull up a digital map and zoom out, the river looks like a jagged vein. Zoom in, and you realize it’s the only reason London exists where it does. It’s also incredibly deceptive. On a map, the water looks static. In real life, the Thames is one of the fastest-moving tidal rivers in the world.

Where the Thames River on Map Actually Starts (And Why Maps Lie)

If you search for the Thames river on map and scroll all the way to the west, you’ll find yourself at a spot called Thames Head near Kemble in Gloucestershire. Here’s the thing: if you go there in person during a dry summer, you might find... nothing. Just a stone monument and some grass.

Standard cartography makes it look like a continuous flow of water. In reality, the "source" is a seasonal spring. Geographers have argued for centuries about whether this is the true start. Some claim the Seven Springs in Gloucestershire is the real source because it adds more length to the river, but tradition usually wins out in England.

As the river trickles toward Oxford, it undergoes a bit of an identity crisis. On many local maps, it’s not even called the Thames; it’s the River Isis. This is basically a Victorian-era quirk that stuck around. It’s the same water, the same banks, but if you’re looking at a map of Oxford’s rowing tracks, don’t be surprised if the word "Thames" vanishes entirely. It’s these little regional eccentricities that standard Google Maps views often gloss over.

The Liquid History of the "Big Bend"

The most recognizable part of the Thames river on map is the dramatic U-turn it takes around the Isle of Dogs in East London. From a bird’s-eye view, it looks like a thumbprint. This isn't just a random curve. It’s the site of the old Royal Docks, once the busiest port in the world.

✨ Don't miss: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

When you’re looking at this specific bend on a map, you’re looking at the heart of the British Empire's logistical power. The land inside that loop is called Canary Wharf now, filled with glass skyscrapers and bankers. But 150 years ago, it was a marshy mess of timber, spices, and sugar.

Interestingly, the river is much deeper here than maps suggest. While a 2D map shows width, it doesn't show the massive underwater canyons dredged out to allow huge container ships to pass. The Thames is a "macrotidal" river. This means the water level can drop or rise by over seven meters in a single day. If you’re looking at a map to plan a walk along the shore, you better check the tide tables first, or that "beach" you saw on the map will be six feet underwater by the time you arrive.

The Secret Islands You Miss When You Don't Zoom In

One of the coolest things about studying the Thames river on map is spotting the "eyots." An eyot (pronounced 'eight') is a small island in the river. Most people know about Eel Pie Island because of its rock and roll history—The Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd played there—but there are over 180 islands in total.

- Tagg's Island: Famous for its eccentric houseboats and a history involving a massive floating hotel.

- Monkey Island: No, there aren't monkeys. It’s likely a corruption of "Monks Island." It’s home to a luxury hotel now.

- Raven's Ait: A tiny island used for weddings and events, sitting right in the middle of the stream near Kingston.

These islands are often just tiny green slivers on a map, but they represent the "Wild Thames." Even in the middle of a massive city, these spots are havens for herons, cormorants, and even the occasional seal. Yes, seals. Biologists at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) have tracked hundreds of harbor and grey seals living in the Thames. They’ve even spotted seahorses and small sharks in the estuary. It’s not the "Great Stink" of 1858 anymore; it’s a living ecosystem.

Navigating the Locks: The River's "Staircase"

If you look at the Thames river on map between Oxford and Teddington, you’ll see dozens of little perpendicular lines. Those are locks. There are 45 of them in total.

🔗 Read more: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

The river isn't a natural slide from the Cotswolds to the sea. It’s actually a series of "reaches" or levels. Without these locks, the Thames would be a shallow, unnavigable stream in some parts and a raging torrent in others. The Environment Agency manages these, and they are essentially the "brakes" of the river.

When you’re looking at a map of the non-tidal Thames (the part above Teddington), you’re looking at a highly managed water garden. It’s where the "Wind in the Willows" vibe comes from. The moment you hit the Teddington Lock, the river changes. It becomes tidal. The maps might look the same, but the physics change completely. From Teddington to the North Sea, the river is legally an extension of the ocean.

The Thames Barrier: The Map's "Shield"

Downstream from Greenwich, there’s a weird metallic structure stretching across the water. On most digital maps, it looks like a series of silver staples. This is the Thames Barrier. It’s one of the largest movable flood barriers in the world.

London is actually sinking. At the same time, sea levels are rising. If a North Sea storm surge hits at the same time as a high tide, Central London would be underwater. The Barrier is the only thing stopping the Thames from reclaiming its ancient floodplains.

When you look at the Thames river on map in the Woolwich area, notice how wide the river gets. The Barrier is positioned at one of the narrowest points of this wide stretch to maximize efficiency. It’s a piece of engineering that most people ignore until the sirens go off for a test closure.

💡 You might also like: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

How to Actually Use a Map of the Thames for Exploration

If you're planning to explore, don't just use a standard road map. You need the Thames Path map. The Thames Path is a National Trail that follows the river for 184 miles.

- Start in the West: If you want solitude and meadows, map out the section between Lechlade and Oxford. It’s quiet, green, and feels like the 19th century.

- The Commuter Stretch: From Reading to Windsor, the map gets busier. You’ll see more rowing clubs and expensive riverside pubs.

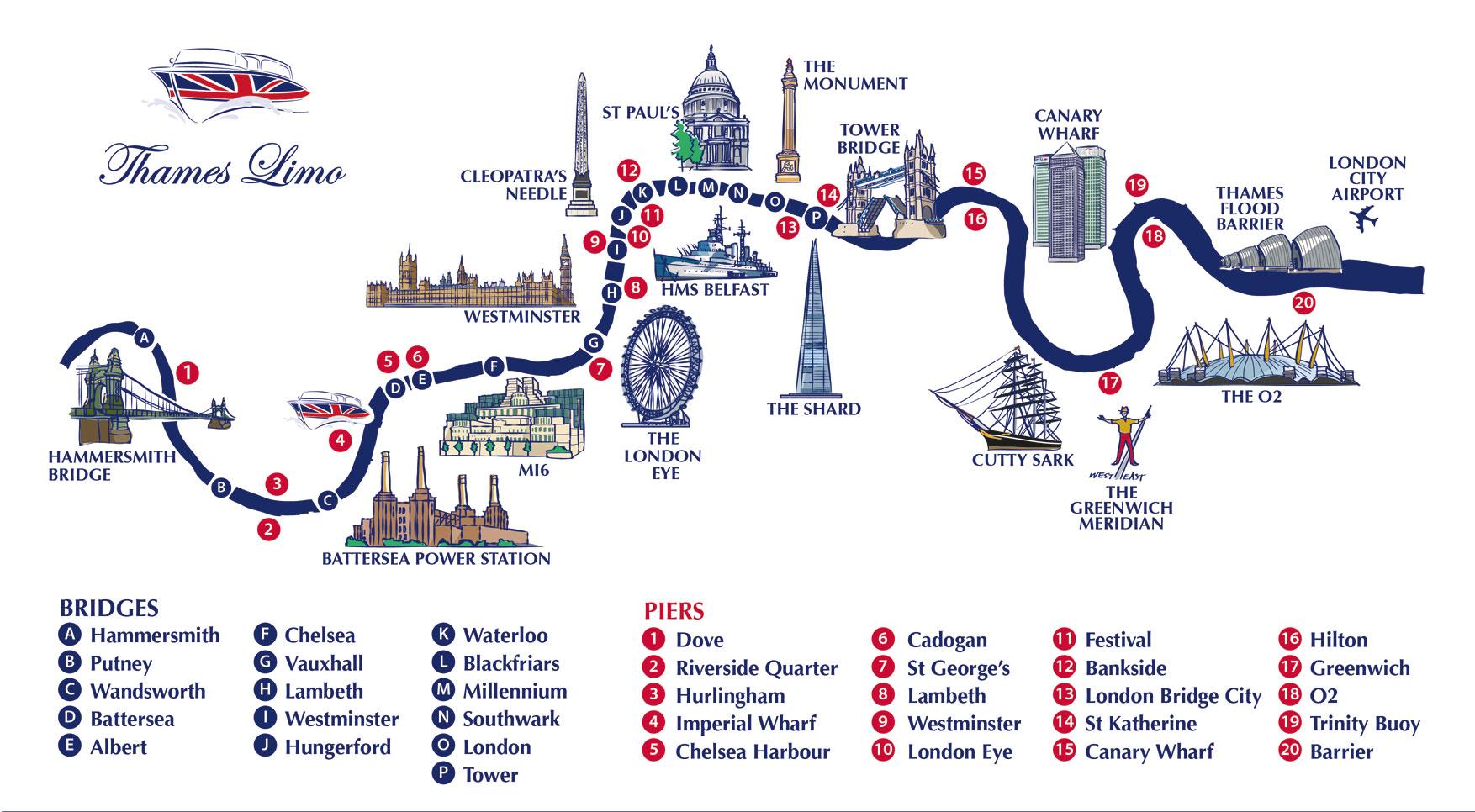

- The Urban Gorge: From Putney to the Tower Bridge, the map is dominated by landmarks. This is where the "Thames on Map" searches usually end up.

- The Industrial Estuary: Past the Barrier, the map turns grey and industrial. This is the "Gateway to the World," where massive ships dock at Tilbury. It’s not "pretty" in a traditional sense, but it’s arguably the most impressive part of the river’s scale.

Honestly, the best way to see the Thames isn't from the shore, though. It’s from the water. Taking a Uber Boat (Thames Clippers) gives you a perspective that a map simply can't provide. You realize just how much higher the city sits than the water, and how the ancient walls hold everything back.

Actionable Next Steps for Mapping Your Visit

If you want to experience the Thames based on what you see on the map, here is how to do it properly.

First, download the National Trails app or use the Long Distance Walkers Association (LDWA) maps. Standard Google Maps often misses the specific public rights of way that hug the riverbank. You don't want to end up stuck in a private marina because you followed a blue line that didn't have a walking path.

Second, check the Port of London Authority (PLA) live charts. If you’re interested in the "moving map," the PLA provides real-time data on ship movements. You can see huge tankers coming in from the Atlantic and heading toward the refineries. It turns a static map into a live-action logistics board.

Third, pay attention to the Tide Times. This is the biggest mistake people make. If you're planning to visit the "beaches" at Southbank or Wapping to do some mudlarking (searching for historical artifacts in the mud), you must have a permit and you must know when the tide is coming in. The Thames rises faster than you can run.

Lastly, look for the "lost rivers" on specialized historical maps. Rivers like the Fleet, the Tyburn, and the Effra still exist—they’ve just been paved over and turned into sewers. They all flow into the Thames. Mapping these hidden veins gives you a much deeper understanding of why London’s topography is so lumpy. You aren't just looking at a river; you're looking at the drainage system of a civilization.