Spheres are everywhere. From the marble in your pocket to the massive gas giants spinning in the far reaches of our solar system, this "perfect" shape dominates the physical world. But honestly, most of us just memorize a formula in 10th grade and never think about it again. We see $A = 4\pi r^2$ and we plug in the numbers. Job done, right? Well, sort of. If you’re trying to calculate how much paint you need for a storage tank or why a soap bubble takes the shape it does, understanding the logic behind finding the surface area of a sphere makes the math feel a lot less like a chore and more like a tool.

The basic math behind finding the surface area of a sphere

Let’s get the "textbook" part out of the way first. The surface area is basically the total area that the outside of the sphere occupies. Imagine you have a baseball. If you could peel the leather off and lay it perfectly flat without stretching it, that flat shape’s area is what we're looking for.

The formula is:

$$A = 4\pi r^2$$

🔗 Read more: Odometer Meaning: Why That Little Number on Your Dash Is Actually a Big Deal

In this equation, A is the surface area, and r is the radius. The radius is just the distance from the dead center of the ball to any point on its edge. Then you have $\pi$ (Pi), which is roughly 3.14159.

Wait. Why the 4? That’s usually where people get tripped up. It feels a bit random. But think about it this way: the area of a flat circle is $\pi r^2$. So, the surface area of a sphere is exactly four times the area of a flat circle with that same radius. It’s a strangely perfect ratio that Archimedes—the Greek math legend—actually discovered over two thousand years ago. He was so proud of this discovery that he allegedly wanted a sphere and a cylinder carved onto his tombstone.

Does the diameter change things?

Sometimes you don't have the radius. You might have the diameter, which is the full width of the sphere. If you've got the diameter ($d$), you just cut it in half to get the radius. Or, if you want to be fancy, you can use the variation $A = \pi d^2$. It gives you the same result. You've just swapped out $4r^2$ for $d^2$ because $(2r)^2$ equals $4r^2$. Math is neat like that.

Why Archimedes was obsessed with this

Archimedes didn't have a calculator. He didn't have Google. He used a method called "exhaustion." Basically, he imagined a sphere fits perfectly inside a cylinder. He proved that the surface area of the sphere is exactly equal to the lateral surface area of that cylinder.

📖 Related: How to Add a Picture in InDesign Without Looking Like a Total Amateur

Imagine a soup can where the sphere touches the top, the bottom, and the sides. If you wrapped a label around that can, the area of that label is the same as the area of the ball inside.

This isn't just a fun trivia fact. It's the basis for how we map the Earth. Map projections like the Mercator projection or the Gall-Peters projection are all different ways of trying to "unpeel" that spherical surface onto a flat map. It's also why maps always look a little distorted at the poles. You can’t flatten a sphere without stretching something.

Real-world situations where this actually matters

You aren't just doing this for a quiz. Engineers use this daily. If you're designing a pressurized tank—like the ones that hold liquid natural gas—you use a sphere. Why? Because a sphere has the smallest surface area for a given volume. This means you use less material to build it, and the pressure is distributed evenly across the whole surface, so it’s less likely to explode.

- Astronomy: When NASA scientists calculate the "albedo" of a planet (how much light it reflects), they need the surface area.

- Medicine: If a radiologist is measuring a tumor, they often treat it as a sphere to estimate how much radiation is needed for the "surface" of the mass.

- Manufacturing: Think about ball bearings. Even a tiny deviation in the surface area can lead to friction issues that wreck a car engine.

Step-by-step: A practical example

Let's say you have a basketball. A standard size 7 basketball has a diameter of about 9.5 inches.

- First, find the radius. $9.5 / 2 = 4.75$ inches.

- Square the radius. $4.75 \times 4.75 = 22.5625$.

- Multiply by 4. $22.5625 \times 4 = 90.25$.

- Multiply by $\pi$ (3.14159). You get roughly 283.5 square inches.

That’s a lot of leather for one ball.

If you're working with metric units, it's the same deal. Just keep your units consistent. If your radius is in centimeters, your answer is in square centimeters. Don't mix and match or your numbers will be total garbage.

Common pitfalls to avoid

People mess this up all the time. The biggest mistake? Forgetting to square the radius. They’ll do $4 \times \pi \times r$ and call it a day. That’s not an area; that’s just a weird number. Area is always two-dimensional, so you must have that $r^2$.

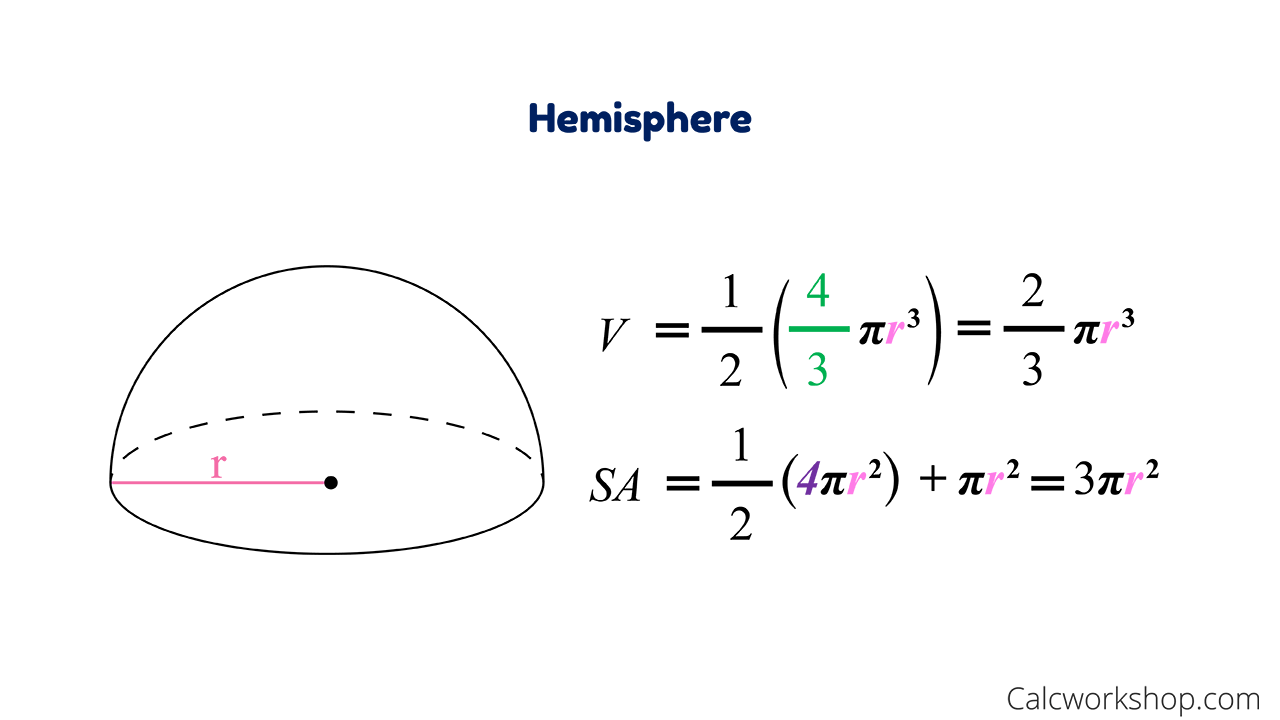

Another one is confusing surface area with volume. Volume is the "stuff" inside ($V = 4/3 \pi r^3$). Surface area is just the "skin." If you're painting a ball, you need surface area. If you're filling it with water, you need volume.

The calculus perspective (for the brave)

If you've ever taken calculus, finding the surface area of a sphere is actually a beautiful proof. You can think of a sphere as a bunch of tiny rings stacked together, or you can use a "surface of revolution." By rotating a semi-circle around the x-axis and integrating, you arrive at that $4\pi r^2$ formula. It’s one of those moments where the complex math simplifies into something incredibly elegant.

Actionable insights for your next project

Knowing how to calculate this is basically a superpower for DIY projects or professional design.

If you’re ever in a spot where you need to calculate the surface area of a sphere quickly without a formula sheet, remember the "Four Circles" rule. Just calculate the area of a circle with the same radius ($\pi r^2$) and quadruple it. It's the fastest mental shortcut.

🔗 Read more: macOS Time Machine Backup: Why Most People Are Doing It Wrong

For anyone working in 3D modeling or game dev, understanding this helps with "texture mapping." When you wrap a 2D image around a 3D sphere, the software is essentially performing these calculations thousands of times per second to ensure the image doesn't look stretched or warped.

To get the most accurate results in a professional setting:

- Use at least five decimal places for Pi ($3.14159$) to avoid rounding errors in large structures.

- Always measure the diameter multiple times and average them; no physical object is a perfect sphere.

- For high-heat applications (like calculating the heat loss of a boiler), remember that materials expand, so your surface area might actually change as the temperature rises.

Whether you're a student trying to pass a test or an engineer trying to build a planetarium, the geometry of the sphere is one of those fundamental bits of knowledge that keeps the world—literally—spinning.

Next time you look at a soap bubble, notice how it's perfectly round. That’s nature trying to minimize surface area through surface tension. Nature already knows the math; you’re just catching up.

To master this, try calculating the surface area of a few household objects—a tennis ball, an orange, or a globe. Use a piece of string to find the circumference if you can't get to the center for the radius, then use $C = 2\pi r$ to solve for $r$ first. Practicing that conversion makes the formula stick way better than just reading about it.