Numbers are weird. You think you know them, and then you try to find the square root of 1000 and realize things aren't as clean as they seemed in third grade. If you’ve ever stared at a calculator and wondered why $31.6227766...$ just keeps going forever, you’re in good company. It’s an irrational number. That basically means it never ends and it never repeats a pattern. It’s just chaos in decimal form.

Most people just round it to 31.6 or maybe 31.62. But honestly, depending on whether you’re a carpenter, a coder, or a math student, that rounding might actually mess you up.

What is the Square Root of 1000 anyway?

In its simplest radical form, we write it as $10\sqrt{10}$. To get there, you just break 1000 down into $100 \times 10$. Since the square root of 100 is 10, it steps outside the radical, leaving the other 10 trapped inside. It's a neat little trick that mathematicians use to keep things precise without dealing with the messy decimals.

The value is roughly 31.62.

If you square 31, you get 961. If you square 32, you get 1024. So, it makes sense that the answer sits right in that sweet spot between them, though it leans a bit closer to 32.

Why does this matter? Well, think about land. If you have a perfectly square plot of land that is exactly 1,000 square feet, each side is going to be about 31 feet, 7.5 inches long. If you're building a fence, that extra half-inch matters.

The Long Division Method (The Hard Way)

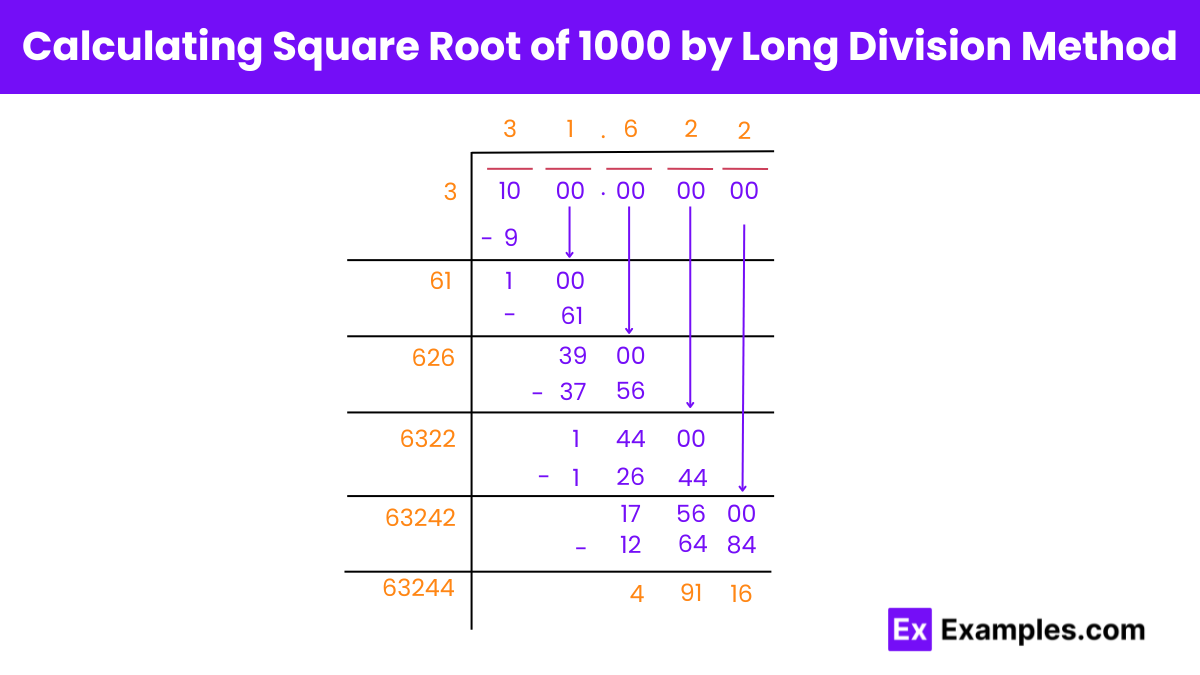

Back before everyone had a supercomputer in their pocket, people used the long division method to find roots. It’s a tedious, soul-crushing process that involves grouping digits in pairs. For 1000, you’d group them as 10 and 00.

First, you find the largest square less than 10. That’s 9. The root is 3.

Subtract 9 from 10, you get 1. Bring down the next two zeros. Now you’re looking at 100.

Then you double your current root (3 becomes 6) and find a number 'x' such that $6x \times x$ is less than or equal to 100.

That number is 1.

$61 \times 1 = 61$.

100 minus 61 is 39.

You keep going like this, adding decimals and bringing down more zeros. It’s how NASA engineers used to do it. Imagine doing that for a living. Honestly, it makes you appreciate the $sqrt()$ function on your phone a lot more.

Why 1000 Is Special in Geometry

In 3D space, things get even more interesting. We often talk about "orders of magnitude." In the metric system, 1000 is the jump from a meter to a kilometer. But when you’re talking about area, the square root of 1000 is the bridge between linear distance and a massive surface area.

Consider a "Great Kiva" or a large circular room. If the floor area is 1,000 square meters, the radius isn't just a simple number. You have to divide by $\pi$ first, then take the root. But if the room is a square, you're looking at that 31.62-meter wall. That’s roughly the length of a professional basketball court plus a little extra. It gives you a physical sense of how big 1000 actually is. It’s larger than you think but smaller than it sounds.

Estimation Tricks for the Lazy

You don't always need a calculator. There's a trick called the Average Method (or Newton's Method if you want to sound fancy).

- Pick a guess. Let’s say 30, because $30^2$ is 900.

- Divide 1000 by 30. You get 33.33.

- Average 30 and 33.33. You get 31.66.

Look at that. With just one round of mental math, you’re already within 0.04 of the actual answer. If you did it again with 31.66, you’d get even closer. This is basically how computers "think." They don't magically know the root; they just guess and refine millions of times per second.

Is it a Rational Number?

Nope. Never.

A rational number can be written as a fraction like $1/2$ or $3/4$. But you cannot write the square root of 1000 as a perfect fraction of two integers. Since 1000 isn't a "perfect square"—meaning no whole number times itself equals 1000—its root is destined to be irrational.

It joins the ranks of $\pi$ and $e$. Numbers that exist in nature but refuse to be tied down to a simple, clean digit.

Real-World Applications

You might think you’ll never use this. You're probably wrong.

If you are a photographer, you deal with f-stops. Those numbers (1.4, 2, 2.8, 4, 5.6...) are actually powers of the square root of 2. While the root of 1000 isn't a standard f-stop, the math governing how light hits a sensor is entirely based on these radical relationships.

In electrical engineering, the RMS (Root Mean Square) voltage often involves taking roots of large numbers. If you have a circuit with specific power requirements, you might find yourself calculating the side of a square wave or the peak of a 1000-watt load.

Even in finance, if you’re looking at "Standard Deviation" or "Volatility," you’re taking the square root of the variance. If your variance is 1000, your risk (volatility) is 31.62%. That's a huge difference in how a broker would treat your portfolio.

Common Mistakes People Make

Most people think the root of 1000 is 100. It’s a weird mental glitch. They see the three zeros and think "10 times 10 is 100, so 100 times 100 must be 1000."

💡 You might also like: See Instagram Without an Account: What Most People Get Wrong

Wrong.

$100 \times 100$ is 10,000.

Another mistake is forgetting the negative root. In pure math, every positive number has two square roots: a positive one and a negative one. So, $-31.622...$ is also technically a square root of 1000. If you’re solving a quadratic equation in a physics class, forgetting that negative sign could literally mean your hypothetical rocket flies into the ground instead of the sky.

Summary of the Numbers

To keep it simple, here is how the value looks across different contexts:

- Exact Value: $10\sqrt{10}$

- Decimal Approximation: $31.6227766$

- Nearest Whole Number: $32$

- Nearest Tenth: $31.6$

Actionable Steps for Using This Math

If you actually need to use the square root of 1000 for a project, stop trying to be a hero with mental math.

First, determine your required precision. If you’re just hanging a picture in a 1,000 sq ft room, "about 31 and a half feet" is fine. If you’re writing code for a graphics engine, use the built-in sqrt() function which uses the floating-point hardware in your CPU to get 15+ decimal places of accuracy.

For students, always provide the simplified radical form ($10\sqrt{10}$) unless the prompt specifically asks for a decimal. Teachers love the radical form because it’s "perfect." Decimals are considered "dirty" in higher-level calculus because they lose information the moment you stop writing digits.

Lastly, if you’re trying to memorize roots, don’t bother with 1000. Just remember that $30^2$ is 900 and $40^2$ is 1600. Knowing those two anchors lets you estimate almost any large root in your head quickly enough to pass a "sanity check" on your work.

Check your calculations twice. It’s easy to misplace a decimal point when dealing with thousands.

Now you know exactly where that number comes from and why it behaves the way it does. It’s just a bridge between the number 10 and its much larger cubic cousins.