You’ve probably been staring at a picture of muscles in shoulder because something feels off. Maybe it’s a sharp pinch when you reach for the coffee mug on the top shelf, or perhaps you’re just trying to figure out why your gym progress has stalled despite hitting lateral raises every single day. The shoulder is a nightmare of engineering. It’s basically a golf ball sitting on a tee, held together by a complex web of "rubber bands" that we call tendons and muscles. Most people think of the shoulder as just the "deltoid," that meaty cap that gives athletes their silhouette. But if you look at a high-quality anatomical diagram, you’ll realize the deltoid is just the curtain hiding a much more chaotic backstage crew.

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body. That's a blessing and a curse. Because it can move in almost every direction, it relies less on bone-to-bone stability and almost entirely on muscular coordination.

Why a Standard Picture of Muscles in Shoulder Can Be Misleading

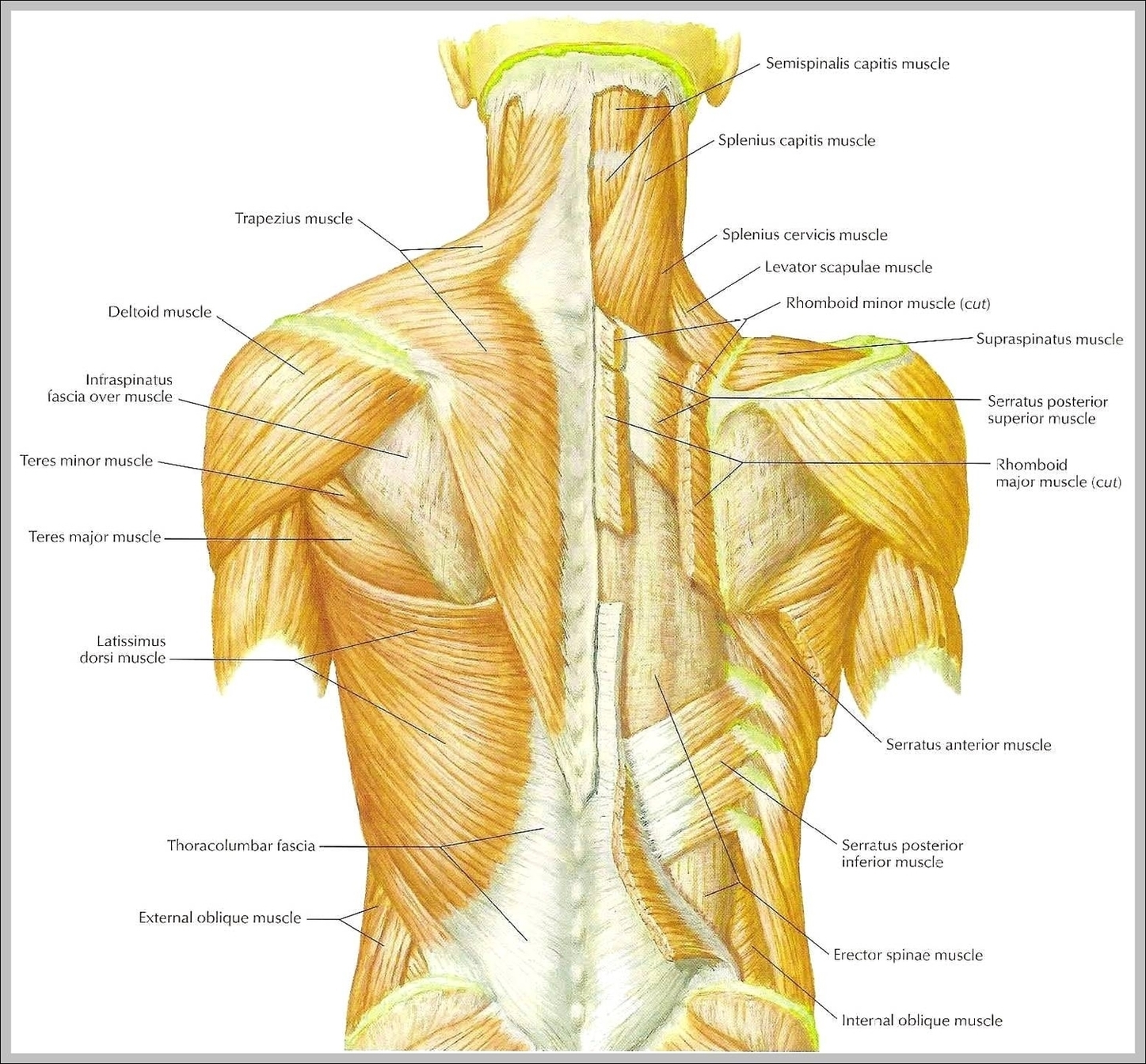

When you search for a picture of muscles in shoulder, you usually get a clean, color-coded map. The deltoids are red, the trapezius is purple, and the rotator cuff is tucked neatly underneath. Real life is messier. Muscles don't just sit next to each other; they weave, overlap, and share connective tissue. For instance, the long head of the biceps actually travels through the shoulder joint to attach to the top of the socket. Most diagrams miss the depth. They show the superficial layer—the stuff you see in the mirror—but skip the deep stabilizers that actually do the heavy lifting of keeping your arm from popping out of its socket.

Dr. Kevin Wilk, a renowned physical therapist who has worked with athletes like Derek Jeter, often emphasizes that shoulder health is about the "rhythm" between the shoulder blade and the arm bone. This is called scapulohumeral rhythm. If you're looking at a static image, you aren't seeing that rhythm. You're seeing a snapshot of a system that is meant to be in constant, fluid motion.

The Big Three: Understanding the Deltoid Layers

The deltoid is actually three distinct sets of fibers. You have the anterior (front), lateral (middle), and posterior (rear) heads.

✨ Don't miss: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

- Anterior Deltoid: This is what gets fried during bench presses. If your front shoulder hurts after chest day, this is usually the culprit.

- Lateral Deltoid: This provides the width. It’s responsible for abduction, or lifting your arm out to the side.

- Posterior Deltoid: Most people ignore this one. It sits on the back of the shoulder and helps pull the arm backward.

Neglecting that rear portion is why so many people have "caveman posture." Their front muscles are too tight and strong, pulling the shoulders forward, while the back muscles are overstretched and weak. When you look at a picture of muscles in shoulder from the side, pay attention to how small that rear deltoid looks compared to the front. It needs intentional work to balance the joint.

The Rotator Cuff: The Four Muscles That Actually Matter

Underneath the big, flashy deltoid lies the rotator cuff. These are the four muscles—SITS is the acronym everyone uses—that provide the real stability.

- Supraspinatus: This tiny muscle lives in a very crowded neighborhood. It runs through a narrow bony tunnel. When people talk about "impingement," they usually mean this muscle or its tendon is getting squashed.

- Infraspinatus: It covers the back of your shoulder blade. Its main job is external rotation—think of the motion of hitchhiking.

- Teres Minor: This is the Infraspinatus's little sidekick. They work together to stabilize the back of the joint.

- Subscapularis: This one is weird because it’s on the underside of your shoulder blade, sandwiched between the blade and your ribs. It’s the primary internal rotator.

If you’re looking at a picture of muscles in shoulder and you don't see these four, you’re only looking at half the story. The rotator cuff acts like a centering mechanism. As the big deltoids pull the arm up, the rotator cuff pulls the "ball" of the arm bone down into the "socket." If the cuff is weak, the ball slides up and pinches the surrounding tissues. It’s a mechanical failure that leads to chronic pain.

Don't Forget the "Hidden" Contributors

The shoulder doesn't end at the shoulder. It's connected to your neck via the levator scapulae and trapezius. It’s connected to your back via the latissimus dorsi. It’s even connected to your chest through the pectoralis minor.

🔗 Read more: Barras de proteina sin azucar: Lo que las etiquetas no te dicen y cómo elegirlas de verdad

I’ve seen so many people try to fix "shoulder pain" by stretching their shoulders, only to realize the issue was actually a tight pec minor pulling the shoulder blade into a bad position. If the shoulder blade (scapula) can’t move, the shoulder joint itself has to overcompensate. This is why a truly helpful picture of muscles in shoulder should ideally show the relationship between the rib cage and the scapula. The "serratus anterior" is a muscle that looks like fingers on your ribs; it’s the primary muscle that keeps your shoulder blade glued to your back. If that muscle is weak, you get "winging scapula," which is a recipe for a labrum tear down the road.

Analyzing Movement Through Anatomy

Take a second and move your arm in a big circle. Feel that? That’s a coordinated dance between roughly 17 different muscles.

When you look at a picture of muscles in shoulder, try to visualize the line of pull. Muscles can only pull; they can't push. The direction the fibers run tells you exactly what that muscle does. The trapezius fibers run in three different directions (upper, middle, lower) because it has to pull the shoulder blade up, back, and down depending on what you’re doing.

Most people have "upper trap dominance." We carry our stress in our necks. We shrug when we lift weights. We shrug when we type. This creates a massive imbalance where the lower trapezius—which is supposed to pull the shoulder blade down and back—atrophies. When you look at an anatomical chart, notice how far down the back the lower trapezius actually goes. It’s much lower than you’d think, reaching toward the middle of the spine.

Common Misconceptions Found in Basic Diagrams

A huge mistake people make when studying a picture of muscles in shoulder is assuming that "bursae" are muscles. They aren't. They are fluid-filled sacs that act as cushions. If you see a blue or translucent blob in a diagram, that's likely a bursa. If it gets inflamed (bursitis), it can feel exactly like a muscle tear, but the treatment is totally different.

💡 You might also like: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Also, many diagrams fail to show the labrum. The labrum is a ring of cartilage that deepens the socket. Think of it like a rubber gasket. Because it’s not a muscle, it doesn't show up in red on most "muscle" pictures, but it’s the foundation everything else attaches to. If the labrum is torn, no amount of muscle strengthening will fully fix the instability.

Actionable Steps for Shoulder Health

Stop just looking at the picture of muscles in shoulder and start applying what the anatomy is telling you. Understanding the layout is the first step toward not hurting yourself.

- Prioritize Posterior Work: For every "push" exercise (bench press, overhead press), do two "pull" exercises (rows, face pulls). This keeps the front-to-back tension balanced.

- Train the Serratus: Do "scapular pushups." Stay in a plank and move your chest up and down just by moving your shoulder blades. This wakes up the serratus anterior and stabilizes the scapula.

- External Rotation is Non-Negotiable: Use light resistance bands. Keep your elbow tucked to your side and rotate your hand outward. This targets the infraspinatus and teres minor specifically.

- Assess Your Posture: If your palms face backward when you stand naturally, your shoulders are internally rotated. Focus on stretching the pec minor and strengthening the lower traps to flip those palms forward.

- Soft Tissue Release: Use a lacrosse ball. Pin it between your shoulder blade and a wall. Move around until you find a "hot spot" in the infraspinatus. Hold for 30 seconds. This releases the tension that diagrams can't show.

The shoulder is a masterpiece of evolution, but it's fragile. It’s the price we pay for being able to throw a baseball or reach behind our backs. By understanding that the picture of muscles in shoulder is actually a map of interconnected pulleys, you can move better and avoid the orthopedic surgeon's office. Focus on the stabilizers, respect the rhythm of the shoulder blade, and don't ignore the muscles you can't see in the mirror. Balance is everything in this joint.

Resources for Further Study

- The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) provides detailed breakdowns of rotator cuff pathology.

- Dr. Kelly Starrett’s "Becoming a Supple Leopard" offers deep insights into shoulder torque and positioning.

- Gray’s Anatomy (The textbook, not the show) remains the gold standard for seeing how these muscles actually intersect in three-dimensional space.

To truly understand your shoulder, you have to look past the skin and the superficial "mirror muscles." Start by identifying where your specific tension lies and map it to the deep structures of the rotator cuff. Once you identify the weak link—usually the lower traps or the serratus—you can begin corrective exercises that restore the natural mechanics of the joint. Consistent, low-intensity activation of these stabilizers is more effective for long-term health than heavy lifting with poor form.