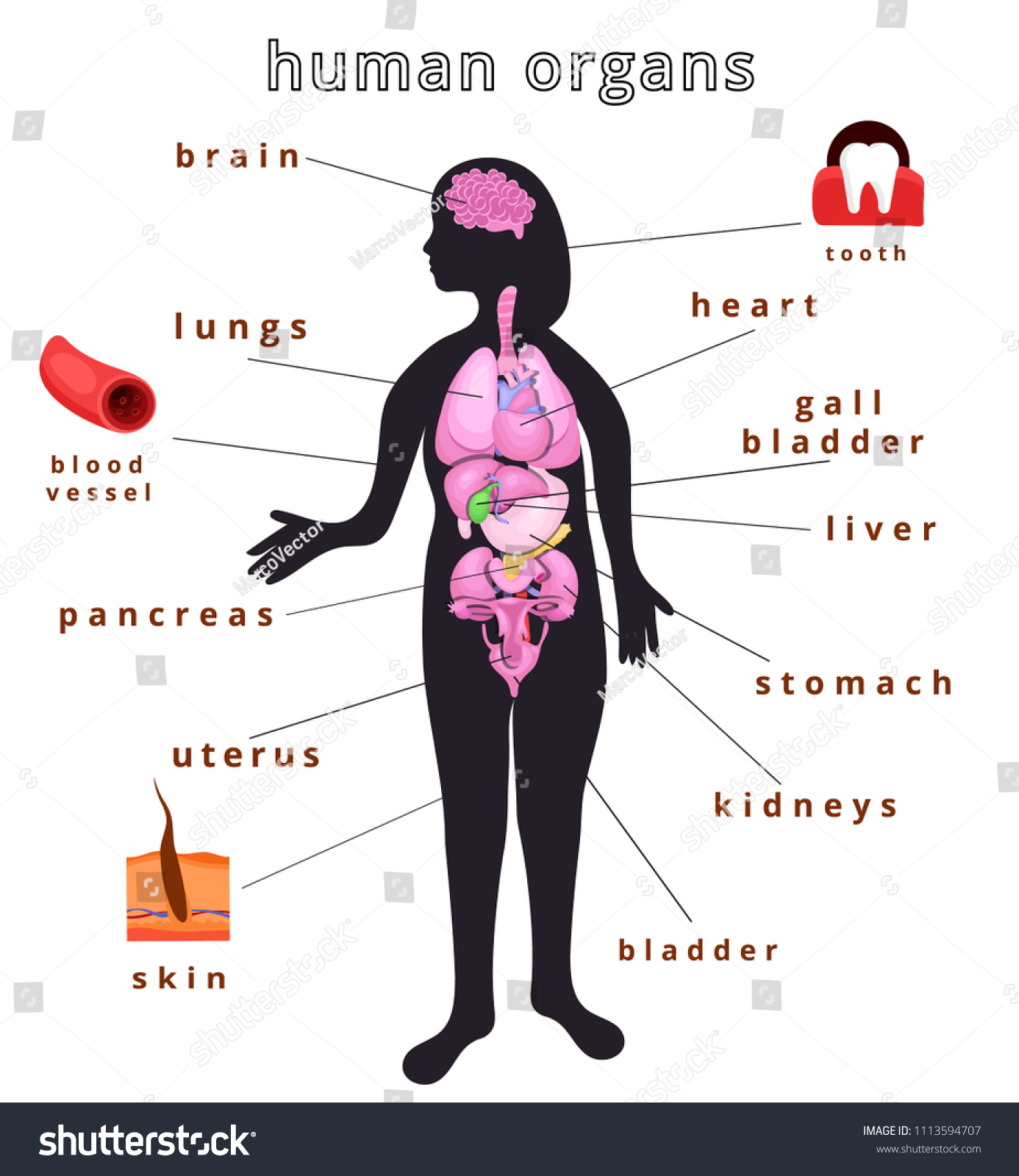

You’ve probably stared at a picture of human anatomy organs in a doctor's office and felt that weird mix of awe and total confusion. It looks like a tangled mess of sausages and tubes. Honestly, it kind of is. But here’s the thing: most of the diagrams we see are lies. Not malicious lies, just "simplifications" that make our bodies look like tidy, color-coded machines when the reality is way more crowded and messy.

If you’re looking for a visual to understand where your gallbladder is or why your lower back hurts, you need to know what you’re actually looking at. Most people think their stomach is behind their belly button. It isn't. It's much higher, tucked under the ribs on the left. This gap between what we see in a quick Google image search and the actual biological reality is why so many people misdiagnose themselves or get confused during medical consultations.

Why Your Internal Map is Probably Wrong

Most diagrams use what's called "Standard Anatomical Position." This is basically the body's version of a mugshot. Feet forward, palms out. It’s useful for surgeons, but for a regular person trying to find their spleen? It’s not always helpful.

Our organs don't just float in space. They are packed in tight. Like, really tight. There is almost zero "empty" space inside your abdominal cavity. Everything is shrink-wrapped in a thin membrane called the peritoneum. When you see a picture of human anatomy organs that shows big gaps between the liver and the stomach, that’s just for clarity. In real life, they are smooshed together.

The Liver: The Quiet Giant

The liver is the absolute unit of the upper abdomen. It’s huge. It weighs about three pounds and sits mostly on your right side. If you look at a high-quality medical illustration, like those from the Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy, you’ll see it actually overlaps a significant portion of the stomach. Most people assume the liver is just a small wedge. Nope. It’s the largest internal organ, and it’s basically a chemical processing plant that never takes a day off.

📖 Related: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

The Intestinal Maze

Then there's the small intestine. It’s roughly 20 feet long. Think about that. Twenty feet of tubing coiled up in your belly. When you see a picture of human anatomy organs focusing on the gut, the colors are usually fake. The small intestine isn't bright pink, and the large intestine isn't a dull grey. They’re all sort of a fleshy, brownish-pink. The "Ascending," "Transverse," and "Descending" colons form a literal frame around the coiled small intestine, which is why pain in your "side" is often just gas moving through the corners of that frame.

Realism vs. Stylization in Medical Images

We have to talk about the difference between a textbook drawing and a 3D render.

Textbooks use "schematic" drawings. These are the ones where the veins are blue and the arteries are red. Fun fact: your veins aren't actually blue. They’re more of a deep maroon or purple. They only look blue through your skin because of how light interacts with your tissue. When you find a picture of human anatomy organs that uses these hyper-saturated colors, it’s a teaching tool, not a photo.

On the flip side, we now have things like the Visible Human Project. Back in the 90s, the National Library of Medicine took a cadaver, froze it, and sliced it into thousands of thin layers to create a digital map. It’s gruesome but incredible. If you want to see what organs actually look like—the way they're marbled with fat and squeezed together—that’s the gold standard.

👉 See also: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

The Lungs Aren't Balloons

Many people see a picture of human anatomy organs and assume the lungs are like two big, empty air sacks. They're actually more like sponges. They are dense. And they aren't symmetrical. The left lung is smaller because it has to make room for the heart, which sits slightly to the left of the center. This "cardiac notch" is a detail often missed in cheap, AI-generated or low-quality clip art.

The Problem With "Generic" Anatomy Pictures

Medical diversity is a huge issue in anatomy visuals. For a long time, almost every picture of human anatomy organs featured a lean, athletic male body. But bodies vary. Age, sex, and even individual genetics change how organs sit.

- Situs Inversus: This is a rare condition where someone’s organs are a mirror image of the norm. The heart is on the right, the liver on the left. It affects about 1 in 10,000 people.

- Pregnancy: Talk about organ displacement. During the third trimester, the stomach is shoved nearly into the chest cavity, and the intestines are squeezed to the sides.

- Visceral Fat: This is the fat that lives under the muscle wall, wrapping around the organs. In many "standard" pictures, this fat is edited out to show the organs clearly, which can give people an unrealistic idea of their own internal landscape.

What to Look for in a Quality Visual

If you are using a picture of human anatomy organs for study or to explain a symptom to a doctor, look for "Cross-Sectional" views. These are like looking at a slice of bread. They show the depth. A "Frontal" or "Coronal" view is just a flat map. It doesn't show you that the kidneys are actually tucked way back against the muscles of your back, protected by your lower ribs. This is why kidney pain feels like a backache, not a stomach ache.

The Tech That’s Replacing 2D Pictures

We’re moving past static images. Now, we have Bio-Digital Humans. These are interactive 3D models where you can "peel" away layers of muscle to see the organs beneath.

✨ Don't miss: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

- CT Scans and MRIs: These are the "real" pictures of your organs. They aren't pretty. They're grainy and black-and-white.

- Endoscopy: This is literally a camera inside the body. It shows the stomach lining as a shiny, wet, pink landscape. It’s way different than the dry, matte drawings in school books.

Seeing a picture of human anatomy organs in 3D helps you realize that the "Retroperitoneal" space is a thing. That’s the area behind the abdominal cavity. Your kidneys and pancreas live back there. They’re like the shy kids at the back of the class, while the liver and intestines take up all the front-row attention.

Common Misconceptions found in Anatomy Diagrams

Let’s clear some stuff up. The heart? It’s not over your left breast. It’s right in the middle of your chest, behind the breastbone (sternum), just tilted a bit to the left. If you’re looking at a picture of human anatomy organs and the heart is way over on the side, it's wrong.

And the brain! It’s not just a grey blob. It’s divided into very specific functional zones. But even the best picture won't show you the "connectome"—the trillions of wiring connections that actually make the organs work. Anatomy is the hardware, but physiology is the software. You can't have one without the other.

Why the Appendix is Always Shown

In almost every picture of human anatomy organs, the appendix is highlighted. It’s that tiny little tail at the start of the large intestine. For years, we thought it was useless. Now, researchers like William Parker at Duke University suggest it might be a "safe house" for good bacteria. So, when you see it on a map, don't just think of it as a ticking time bomb for surgery—it’s actually a backup drive for your gut health.

Actionable Steps for Using Anatomy Pictures Effectively

If you're trying to learn or communicate about your health, don't just grab the first image on a search engine.

- Check the Source: Use reputable sites like the Mayo Clinic, Kenhub, or the Cleveland Clinic. They use professional medical illustrators who understand spatial relationships.

- Look for Multiple Angles: A side view (Sagittal) is often more revealing than a front view (Coronal) for understanding how organs like the bladder and uterus sit.

- Identify the "Landmarks": Find your ribs or your hip bones on the diagram. Use those "hard" points to figure out where the "soft" organs are in your own body.

- Use 3D Tools: If you can, use an app like Complete Anatomy. Being able to rotate the body helps your brain understand that the "picture" is actually a complex, 3D volume.

- Talk to a Pro: If you're looking at a picture of human anatomy organs because something hurts, show the picture to your doctor and say, "Is this where the pain is supposed to be?" They can help correlate the "map" to your "territory."

Understanding your internal layout is basically the ultimate form of self-awareness. It’s easy to feel like our bodies are black boxes, but a good visual breaks that barrier. Just remember that every body is a little bit different, and no single picture can capture the incredible, messy reality of what's happening under your skin right now.