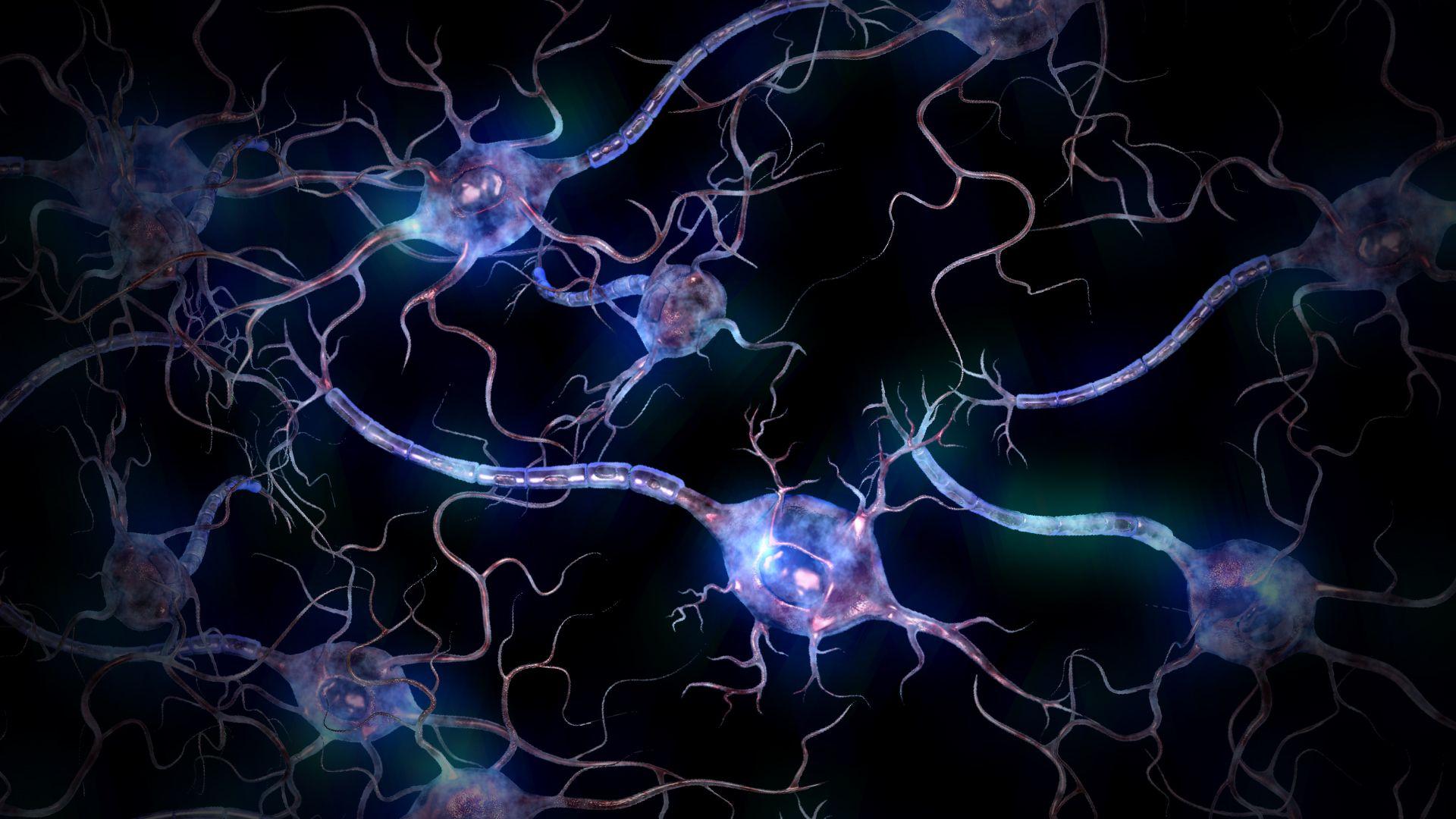

You’ve seen it. That glowing, electric-blue silhouette of a human body, crisscrossed with neon lines that look like a city map at night. It’s the standard photo of nervous system used in every wellness blog and vitamin ad. But honestly? It’s kind of a lie. Or at least, it’s a massive oversimplification that makes your internal wiring look a lot more organized than it actually is.

The human nervous system is messy. It’s wet. It’s incredibly dense. If you were to look at an actual specimen—like the famous "Harriet Cole" dissection or the preserved figures in the Body Worlds exhibits—it doesn't look like a neon light show. It looks like a complex, slightly beige tangle of stringy fibers that somehow manages to control everything from your heartbeat to your weird obsession with 80s synth-pop.

Finding a truly accurate image matters. Whether you’re a student, a bio-hacker, or just someone trying to visualize why their lower back hurts, the visual representation you choose shapes how you understand your own body. Most stock photos ignore the "fuzziness" of the fascia or the way nerves actually weave through muscle. They show the highway, but they forget the traffic and the overgrown weeds on the shoulder.

Why Your Brain Struggles with a Standard Photo of Nervous System

Most people think of nerves as wires. It’s the easiest analogy. Wires carry electricity, nerves carry impulses—same thing, right? Not really. When you look at a high-resolution photo of nervous system structures, you’ll notice that unlike a copper wire, a nerve is a living, breathing organ. It needs its own blood supply. It needs to stretch and glide.

If you look at the work of Dr. Jean-Claude Guimberteau, a French hand surgeon who used endoscopes to film living tissue under the skin, you see something wild. The "wires" aren't static. They are surrounded by a micro-vacuolar system that looks like a fractal web of bubbles and threads. Standard medical illustrations usually strip all that "gunk" away to make the diagram readable. While that’s helpful for passing a biology quiz, it’s terrible for understanding how pain actually works in a living person.

The Problem with 3D Renders

We love 3D renders because they look "clean." They give us a sense of order in a chaotic world. But these digital recreations often get the scale wrong. They make the sciatic nerve look like a thick rope—which it is, relatively—but they miss the billions of microscopic branches that permeate every square millimeter of your skin.

📖 Related: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

You’ve got about 45 miles of nerves in your body. Think about that. 45 miles. Most photos can only show about 1% of that total length before the image becomes a solid block of color. This is why specialized imaging like Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) is becoming so popular. DTI isn't a traditional "photo" but a mapping of water molecule movement in the brain's white matter. It looks like a psychedelic rainbow, but it’s actually one of the most honest ways we have to visualize the brain's connectivity.

The Famous Dissections: When Reality Hits

If you want a real photo of nervous system history, you have to talk about Harriet Cole. In 1888, a janitor named Rufus Weaver at the Hahnemann Medical College spent five months painstakingly dissecting the entire nervous system of a woman named Harriet Cole. He didn't just cut; he cleaned every single filament until he could mount the whole thing on a board.

It is haunting. It looks like a ghost.

Looking at that photo tells you more than a thousand CGI models ever could. You see the density of the brachial plexus—that bird's nest of nerves near the shoulder—and you realize why a neck injury can make your pinky finger go numb. You see how the spinal cord isn't just a tail; it's the trunk of a massive, intricate tree.

What to Look for in a High-Quality Image

If you're searching for an image for a project or for personal understanding, stop looking for "pretty" and start looking for "contextual." A good photo should show:

👉 See also: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

- The Foramina: These are the tiny holes in the vertebrae where nerves exit the spine. If a photo doesn't show the tight squeeze these nerves have to navigate, it's missing the most common site of human pain.

- The Ganglia: These are the "mini-brains" or clusters of nerve cell bodies outside the CNS. They look like little swellings or knots on the nerve.

- Vascularity: Real nerves are pinkish-gray because they are wrapped in tiny blood vessels (the vasa nervorum). If the photo shows them as pure white or bright yellow, it's an abstraction.

The Digital Frontier: Connectomics

We are currently in the middle of a massive project called the Human Connectome Project. The goal is to build a "map" of every neural connection. But here’s the kicker: we can’t actually take a single "photo" of it yet.

Scientists have to take incredibly thin slices of brain tissue—thousands of them—scan them with electron microscopes, and then use AI to stitch them back together. In 2021, a team from Harvard and Google mapped a tiny piece of the human cortex. The resulting "image" was just one cubic millimeter of tissue, but it took 1.4 petabytes of data to store. That’s the scale we’re dealing with. A single photo of the entire nervous system at that resolution is currently impossible. It would require more storage than we probably have on earth.

So, when you see a photo of nervous system on a website, remember you're looking at a map, not the territory. Maps are useful, but they always leave out the mountains and the trees to show you the road.

Misconceptions About Color

Why is everything in anatomy photos yellow? Most textbooks color-code the nervous system yellow, veins blue, and arteries red. This is purely for our benefit. In a real cadaver, everything tends to fade into a brownish-tan after preservation. In a living person, nerves have a pearlescent, shimmery quality. They almost glow under surgical lights. If you find a photo where the nerves look like silk ribbons, you’re looking at something much closer to reality than the high-contrast yellow diagrams.

Why You Should Care About the Visuals

Visualization is a powerful tool in physical therapy and chronic pain management. There’s this concept called "graded motor imagery." Basically, if you can accurately visualize your nervous system moving and gliding without being "pinched," it can actually help reduce pain signals.

✨ Don't miss: Barras de proteina sin azucar: Lo que las etiquetas no te dicen y cómo elegirlas de verdad

But if you’re visualizing a rigid, brittle wire (like in those bad stock photos), your brain might maintain a "protective" state of tension. Seeing a photo of nervous system structures that emphasizes their fluidity and resilience can be literally therapeutic.

Actionable Insights for Finding the Best Imagery

Don't settle for the first Google Image result. If you want the real deal, you have to dig into specific databases.

- Search for "Plastination": This is the process pioneered by Gunther von Hagens. Photos of plastinated nervous systems are the gold standard for seeing the 3D relationship between nerves and bone.

- Check the Allen Brain Institute: They have incredible, high-resolution interactive maps that go way beyond a static JPEG.

- Look for "Gross Anatomy" tags: This will lead you to real photos of medical school dissections rather than digital illustrations. Be warned: it's not for the squeamish, but it is the truth.

- Use Neuroimaging terms: Instead of just "nervous system," search for "tractography" or "fMRI overlay." These give you a functional view—showing what the system is doing, not just what it looks like sitting still.

The nervous system isn't a static object. It's a process. Every time you look at a photo of it, you're looking at the hardware that allows you to experience the software of your life. It’s worth finding a version that doesn't treat that complexity like a simple circuit board.

Next Steps for Better Understanding:

To truly grasp what you're seeing in a photo of nervous system, start by identifying the "Big Three": the Cerebrum (the "thinking" part), the Spinal Cord (the "information highway"), and the Vagus Nerve (the "calm down" system). When you can spot the Vagus nerve—which wanders from your brainstem all the way down to your colon—you'll start to see how your "gut feeling" is actually a physical, structural reality captured in the image.

Focus your research on peripheral nerve architecture if you are dealing with limb pain, or white matter tracts if you are interested in cognitive performance. Seeing the difference between the "gray matter" (the processors) and the "white matter" (the cables) in a cross-section photo is the "Aha!" moment most people need to finally understand how their brain actually functions.