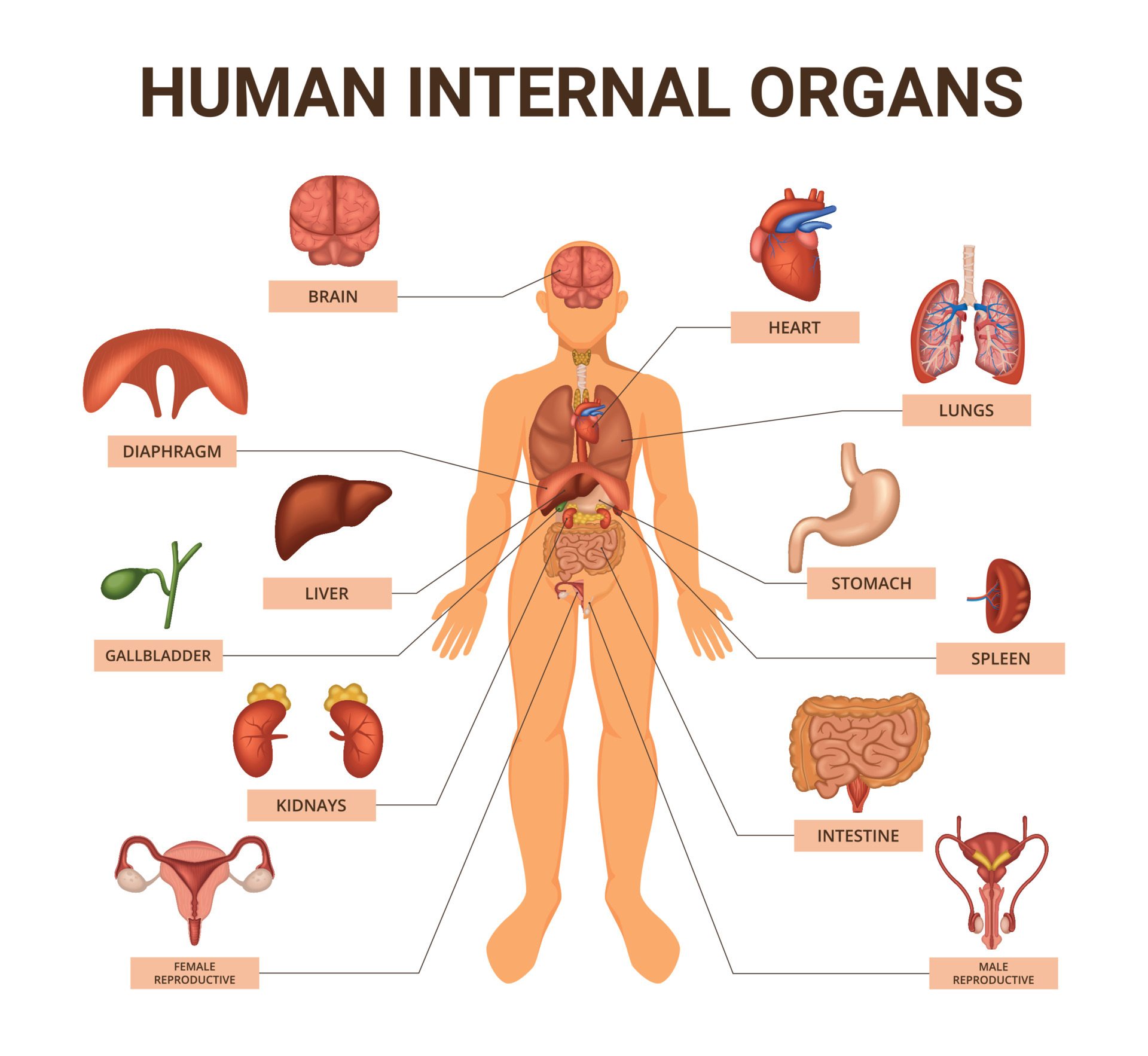

Ever looked at a textbook illustration and thought, "Wow, my insides must be so organized"? Everything is color-coded. The veins are bright blue, the arteries are a vivid cherry red, and the liver is a perfectly smooth, chocolatey-brown wedge. It's clean. It's tidy. Honestly, it's a lie. When you actually look at a real organ pic of human body—whether from a surgical archive or a high-res pathology slide—it’s a messy, glistening, tangled reality that looks nothing like the diagrams we saw in fifth grade.

The human body isn't a Lego set.

It is a fluid, wet, and incredibly cramped environment where organs don't just sit next to each other; they are squished, fused, and wrapped in layers of connective tissue called fascia. Most people searching for an organ pic of human body are trying to visualize where their pain is coming from or perhaps studying for a pre-med exam. But there is a massive gap between the "cartoon" version of us and the actual biological machinery.

What You're Actually Seeing in a Medical Image

When you see a high-quality medical photograph, the first thing that hits you is the color—or lack thereof. Real organs are mostly shades of deep red, pinkish-gray, and yellow (thanks, fat). That "blue vein" thing is purely for your benefit in textbooks. Inside you, veins are more of a dark, translucent purple-maroon because of the deoxygenated blood.

Take the liver, for example. It's the heavy lifter. In a standard organ pic of human body, it looks like a solid mass. In reality, it has a weirdly soft, almost jelly-like consistency that can be easily indented with a finger. It's also much larger than most people realize, tucked up under your ribs on the right side, weighing about three pounds. If you're looking at a photo of a liver and it looks bright yellow or bumpy, you're actually looking at pathology—likely fatty liver disease or cirrhosis. This is why context matters so much when you're browsing medical imagery.

A healthy lung isn't just a pink balloon. It's spongy. If the person lived in a city, that lung is going to have tiny black specks all over it—carbon deposits from breathing air. It's these tiny, gritty details that a 3D render usually misses but a real photograph captures with brutal honesty.

👉 See also: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

The Misleading Nature of 2D Anatomy

You've probably seen those posters in a doctor's office. The "Incredible Human Machine" or whatever they're calling it this year. They show the stomach sitting right in the middle. But wait. Your stomach is actually mostly on the left side, tucked under the diaphragm. And it's not a static shape.

It stretches. A lot.

A photo of an empty stomach looks like a shriveled-up raisin, full of folds called rugae. A photo taken after a Thanksgiving dinner would show a giant, smooth-walled sac. This variability makes a single organ pic of human body somewhat limited. It’s a snapshot in time. Dr. Gunther von Hagens, the anatomist behind the Body Worlds exhibits, changed how we see this by using plastination. He preserved real bodies to show the actual spatial relationships, but even then, the process of drying and "fixing" the tissues changes their appearance. They lose the "wet" look of living biology.

Why Your Interior Is So Crowded

If you've ever watched a laparoscopic surgery video—which is basically a live-action organ pic of human body—the most striking thing is how little room there is. There’s no "empty space" inside you. If there’s a gap, it’s filled with serous fluid or yellow adipose tissue (fat).

Fat isn't just under the skin. It's everywhere. It wraps around the kidneys like a protective packing peanut. It hangs off the intestines in a lacey curtain called the omentum. Surgeons often have to move "curtains" of fat out of the way just to see the organ they’re supposed to be operating on. When you search for anatomy photos, you often get "cleaned" versions where all this connective tissue has been dissected away. It’s helpful for learning names, but it’s not what a surgeon sees when they open a patient up.

✨ Don't miss: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

The Complexity of the Gut

Let's talk about the intestines. Most diagrams show them as a neat coil of garden hose. In a real photo, the small intestine is a 20-foot-long, pinkish-tan tube that is constantly squirming. This movement is called peristalsis. If you saw a still organ pic of human body of the abdomen, you’d see the "mesentery"—a thin, clear-ish membrane that holds the intestines together so they don't get tangled in a knot when you go for a run.

It’s actually quite beautiful in a weird, biological way. The mesentery is filled with blood vessels that look like the branches of a winter tree. Until recently, we didn't even classify the mesentery as its own organ, but now medical science recognizes it as a continuous structure. This just goes to show that how we "see" our organs is constantly changing as our technology improves.

Modern Imaging vs. Old-School Photography

Nowadays, we don't always need a camera to get an organ pic of human body. We have:

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): This uses magnets to flip protons in your body. It’s great for soft tissue. It gives us a "slice" view.

- CT Scans: These are basically 3D X-rays. They’re amazing for seeing the density of organs.

- Ultrasound: It’s grainy and looks like a weather map, but it’s the only way to see organs moving in real-time without surgery.

But even with these, there’s a loss of "humanity." A CT scan of a heart shows the chambers and the valves, but it doesn't show the glistening, muscular power of a real heart. A real heart is incredibly tough. It's a dense muscle that feels more like a firm steak than a balloon. When you see a photo of a heart that has been removed for transplant, it looks remarkably pale once the blood is drained out.

The Ethics of Anatomy Photos

It’s important to remember where these images come from. Most high-quality, professional organ pic of human body sets come from one of two places: cadaveric donation or surgical recording.

🔗 Read more: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

Medical schools rely on the incredible gift of body donation. When you're looking at a photo of a dissected forearm or a cross-section of a brain, you're looking at a person's final contribution to science. This is why most reputable medical sites (like Netter’s or the Mayo Clinic) use a mix of highly accurate illustrations and carefully curated photographs. They want to respect the dignity of the donor while providing the necessary clarity for students.

Practical Ways to Use These Images

If you’re looking at these images because you’re worried about a symptom, here’s a tip: don’t self-diagnose based on color. I've seen people freak out because their "liver area" hurts and they saw a photo of a dark, healthy liver and assumed theirs must be "bruised." You can't see a bruise on a liver through your skin.

Instead, use these images to understand the "where."

If you have pain in your lower right abdomen, looking at an organ pic of human body will show you that's exactly where the cecum (the start of the large intestine) and the appendix live. If you have pain under your left shoulder blade, an anatomy map might show you that it’s actually referred pain from your spleen or stomach.

Actionable Steps for Better Biological Understanding

Don't just look at one photo and call it a day. Biology is 3D and dynamic.

- Use Interactive 3D Apps: Instead of static images, use tools like BioDigital or Complete Anatomy. These let you "peel" layers of muscle and fat away to see how the organs sit behind them.

- Search for "Gross Anatomy": If you want the unvarnished, non-illustrated truth, this is the medical term for things visible to the naked eye. It will lead you to actual medical school resources rather than Pinterest diagrams.

- Check the Source: Ensure the image is from a university or a verified medical board. There is a lot of "health-adjacent" content online that uses AI-generated images which are often anatomically impossible—missing lobes of the lungs or putting the gallbladder on the wrong side.

- Look for Cross-Sections: A "top-down" slice (axial view) is often more helpful for understanding how organs lean against each other than a front-facing (coronal) view.

- Watch Surgical "B-Roll": Many teaching hospitals post narrated surgeries on YouTube. Watching a surgeon move an organ to get to another provides a sense of the texture and "slidability" of our insides that a photo never can.

Understanding your body through a real organ pic of human body takes away some of the mystery and, honestly, some of the fear. Once you see that your organs are part of a tightly packed, resilient system, you start to appreciate why staying hydrated and moving around matters so much. Everything in there needs room to breathe, slide, and function. Your body isn't just a collection of parts; it's a living, breathing landscape.