You’re looking at a map of Greece with Sparta and probably expecting to see something grand. Maybe a massive stone fortress or a sprawling city-state that rivals the Acropolis in Athens. Honestly? You might be disappointed at first glance. If you zoom into the Peloponnese, that thumb-shaped peninsula hanging off the bottom of mainland Greece, you’ll find Sparta tucked away in the Eurotas River valley. It’s surrounded by the massive, jagged peaks of the Taygetos Mountains.

It’s not on the coast. That’s the first thing people get wrong.

Sparta was a land power. While Athens was busy building a navy and looking out at the Aegean, the Spartans were inland, isolated, and focused entirely on the soil beneath their feet. When you look at a modern map, you’ll see the town of Sparti. It sits right on top of the ancient site, but the "vibe" is completely different from the cinematic version we get in movies.

Where Exactly Is Sparta on the Map?

Geography is destiny. In Sparta’s case, this isn't just a cliché. If you pull up a map of Greece with Sparta highlighted, look at the southern region known as Laconia. Sparta sits in a fertile plain, but it’s essentially trapped. To the west, the Taygetos Mountains rise up to nearly 8,000 feet. They are brutal, steep, and snow-capped for much of the year. To the east is the Parnon range.

This created a natural fortress.

Ancient historians like Thucydides actually predicted our modern confusion. He famously wrote that if Sparta were deserted and only the foundations of the temples and public buildings remained, people in the future would find it hard to believe the city was ever as powerful as its fame suggested. He was right. Unlike Athens, which used stone and marble to scream about its greatness, Sparta was a collection of villages.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

They didn't build walls.

Why? Because they believed their men were their walls. If you’re tracking the map of Greece with Sparta for a road trip, you’ll take the A7 motorway down from Athens, cutting through the mountains of Arcadia. It’s a drive that reveals exactly why Sparta remained so culturally distinct; it was a mission just to get there.

The Strategic Reality of the Peloponnese

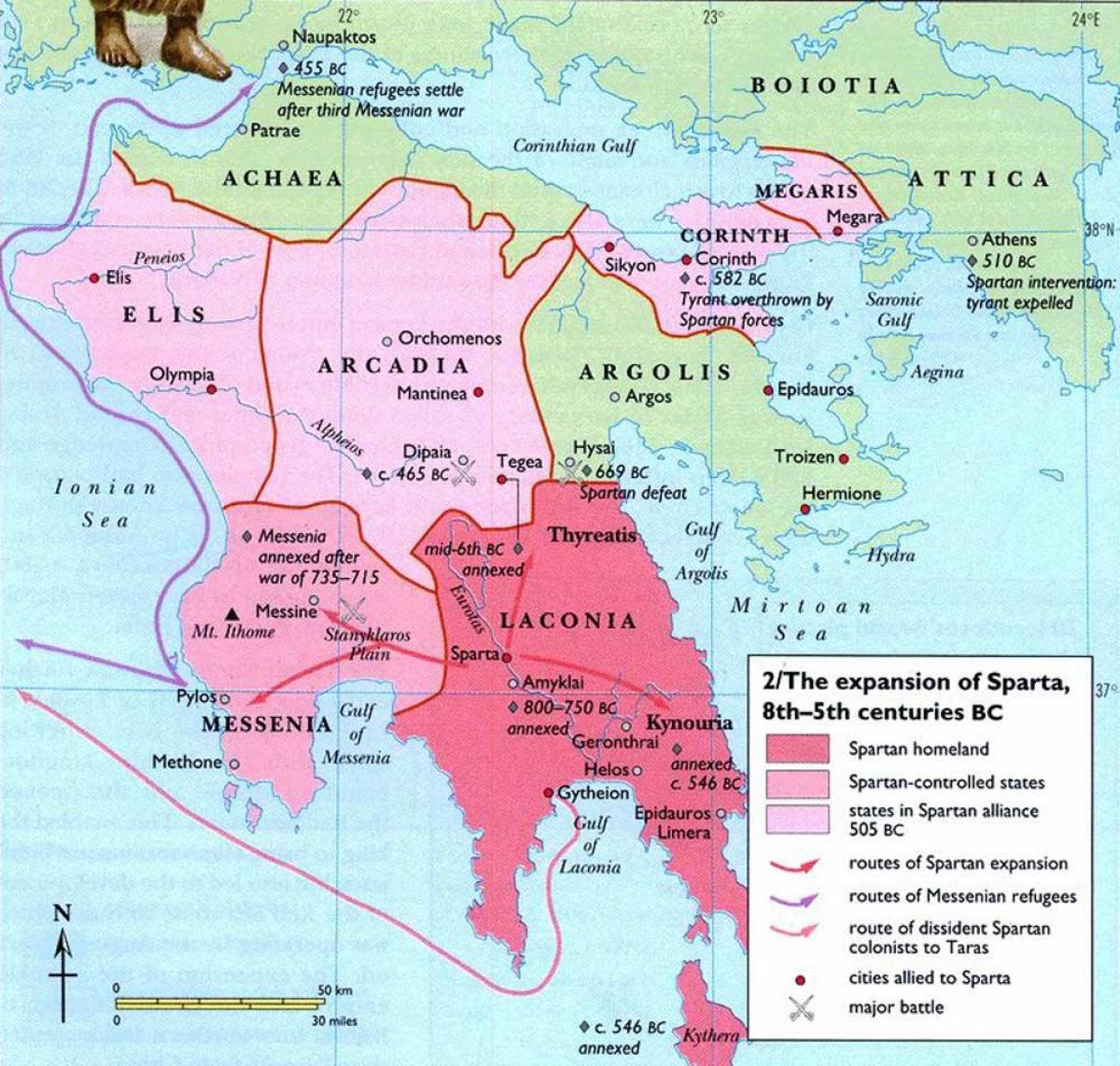

Understanding the map of Greece with Sparta requires looking at the "Peloponnesian League." Sparta wasn't just a single dot on the map; it was the head of a massive snake. By the 5th century BCE, Sparta had effectively bullied or allied with almost every city in the Peloponnese except for Argos.

- Messenia: This is the region to the west, over the Taygetos mountains. Sparta conquered it early on. This is where the Helots—the enslaved population that farmed the land—came from. Without the map of Messenia, you don't have Sparta. The Spartans needed that land to feed their professional army.

- The Eurotas River: This was the lifeblood. It provided the water needed for a settlement that was otherwise cut off from easy maritime trade.

- Gytheio: If you look south of Sparta on the map, you’ll see this port town. This was Sparta’s naval base, though they were always awkward sailors compared to the Corinthians or Athenians.

Most people don't realize how small the actual "city" was. It was really five separate villages: Pitana, Mesoa, Limnae, Conoura, and Amyclae. They eventually merged, sort of. But it never had that "urban" feel. It felt like a military camp because, well, it was.

Misconceptions About the Spartan Landscape

There’s a common myth that Sparta was a barren, harsh wasteland. People think "Spartan" means "empty." Look at a topographical map of Greece with Sparta and you'll see the opposite. The Eurotas valley is incredibly lush. It’s full of olive groves and citrus trees today. In antiquity, it was one of the most productive agricultural zones in Greece.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

The "harshness" wasn't the land; it was the social system.

The mountains didn't just keep enemies out; they kept the Spartans in. They were terrified of "foreign contamination." They didn't want their citizens traveling and getting weird ideas about democracy or luxury. This geographic isolation fed their legendary xenophobia. While Athens was a cosmopolitan hub of trade and philosophy, Sparta was a locked-room mystery.

The Taygetos Mountains and the "Apothetae"

You’ve probably heard the story about Spartans throwing "unfit" babies off a cliff. On your map, look for the Kaiadas ravine in the Taygetos range. For a long time, people thought this was just a grim legend. However, modern archaeological digs in the area have found human remains. Interestingly, many of the bones belong to adults—likely criminals or prisoners of war—rather than just infants.

The landscape was used as a tool for eugenics and judicial punishment. The mountains weren't just scenery; they were a part of the legal system.

How to Use a Map of Greece with Sparta for Modern Travel

If you’re actually going there, don't just put "Sparta" into your GPS and expect a theme park. Ancient Sparta is largely gone, replaced by the modern grid-planned city of Sparti, which was rebuilt in the 19th century by King Otto.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

- The Acropolis of Sparta: North of the modern town. You can see the ruins of a theater that was one of the largest in Greece, but it dates mostly from the Roman period.

- The Menelaion: This is across the river. It’s a shrine to Helen and Menelaus. The view from here gives you the best "map" perspective of the entire valley. You see the river, the town, and the wall of mountains.

- Mistras: This is a "must." It’s just a few kilometers west. It’s a Byzantine ghost city clinging to the side of the Taygetos. While it’s much later than the "300" era, it shows how the geography of Sparta was used for defense in the Middle Ages.

Honestly, the best way to "see" ancient Sparta on a map is to look at the passes. Look at the Langada Pass that connects Sparta to Kalamata. It’s a harrowing, winding road. Driving it today makes you realize why an invading army would think twice about trying to march into the Spartan heartland.

The Tactical Shift: Why the Map Changed

Everything changed for Sparta in 371 BCE at the Battle of Leuctra. If you look at a map of central Greece, near Thebes, that’s where the Spartan dream died. The Theban general Epaminondas didn't just beat them in battle; he used the map against them.

He marched into the Peloponnese and freed the Messenians.

By liberating the land to the west, he took away Sparta's grocery store. He built a giant wall around the new city of Messene. Suddenly, the map of Greece with Sparta showed a city-state that was trapped, poor, and stripped of its labor force. Sparta never recovered. It became a "tourist" destination for Romans who wanted to see the weird "warrior people" do their traditional dances and rituals.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

To truly understand the map of Greece with Sparta, you have to look past the modern borders and see the verticality of the terrain.

- Don't ignore the Mani Peninsula: South of Sparta is the Mani. The people there claim to be the direct descendants of the Spartans. The geography there is even more rugged and remained independent even during the Ottoman occupation.

- Check the elevation layers: If you’re using a digital map, turn on the 3D terrain. Notice how Sparta is essentially "walled in" by nature. This explains their lack of city walls and their focus on heavy infantry.

- Visit the Archaeological Museum of Sparta: It’s small but contains the famous "Leonidas" bust. It helps put a face to the landscape.

- Combine your trip: Don't just do Sparta. You need to see Pylos and Messene. Seeing the scale of the territory the Spartans controlled—and eventually lost—is the only way to grasp the rise and fall of this power.

When you look at the map of Greece with Sparta, you’re looking at a site of extreme contradiction. It’s a fertile valley that produced a culture of self-denial. It’s a place with no walls that dominated the walled cities of the north for centuries. The map tells you why they were strong, but it also tells you why they were eventually doomed to fade away into the olive groves.