He was there for only about two minutes. That's it. That is the entire window of time it took for Abraham Lincoln to deliver the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863. Because the speech was so brief, the photographers of the day—lugging around massive glass plates and chemicals—barely had time to set their focus.

For nearly a century, people thought no photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg actually existed. It seemed impossible. Thousands of people were there, and a dozen cameras were pointed at the platform, yet the President appeared to be a ghost. It wasn’t until 1952 that a Josephine Cobb, working at the National Archives, zoomed in on a glass plate negative and found him.

Honestly, he looks like a blur. You have to squint. But once you see him, the whole historical moment shifts from a textbook illustration to a gritty, muddy reality.

The Crowds, the Mud, and the Missing Shot

Gettysburg in November was a mess. The town was still reeling from the battle that had happened only four months prior. The air probably still smelled like death, and the ground was churned into a soup of cold Pennsylvania mud.

David Wills, the local lawyer who organized the cemetery dedication, invited Lincoln almost as an afterthought. He expected a "few appropriate remarks." He didn't expect a masterpiece.

Photographers like David Bachrach and Alexander Gardner were on-site, but they were struggling. 19th-century photography wasn't "point and shoot." It was a grueling process of coating a glass plate in collodion, rushing it into the camera while wet, exposing it for several seconds, and then rushing back to a darkroom wagon to develop it.

If you moved, you vanished.

Lincoln stood up, spoke 272 words, and sat down before most of the cameramen could even pull their lens caps. This is why the most famous photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg isn't a portrait of him speaking. It’s a shot of him sitting down, hatless, lost in a sea of top hats and dignitaries.

He’s just a speck. A tall, gaunt speck with a messy head of hair.

🔗 Read more: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Zooming into the 1863 Glass Plates

The main image everyone talks about was taken by David Bachrach. For decades, it was just labeled as a general view of the speaker’s platform.

In the 1950s, researchers started looking closer. If you look at the center of the crowd on the platform, you see a man with a distinctively high forehead and a beard. He’s looking down. He’s probably adjusting his coat or checking his notes.

That’s him.

It’s a humble image. It doesn't show a titan of history carved in marble; it shows a tired, grieving father who had recently lost his son Willie and was currently suffering from a mild case of smallpox.

Yes, Lincoln likely had variola minor that day. He felt weak. He was dizzy. When you look at the photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg with that context, the "blurriness" feels more like a reflection of his physical state. He was a man holding a breaking country together while his own body was failing him.

The Second Photo Debate

History is never settled. Never.

For a long time, the Bachrach photo was the only one. Then, in 2007, an amateur historian named John Richter claimed he found another. He was looking at a 3D stereoview taken by Alexander Gardner.

Richter pointed to a figure on horseback in the distance, wearing a tall hat.

💡 You might also like: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

"That's him," he said.

But wait. Other historians, like Christopher Oakley, a former Disney animator with a penchant for facial recognition, disagreed. Oakley spent years mapping the 3D coordinates of the platform. He thinks Richter found the wrong guy.

Oakley’s research suggests Lincoln is actually in a different spot in the Gardner photos, visible only if you look past a certain soldier's shoulder.

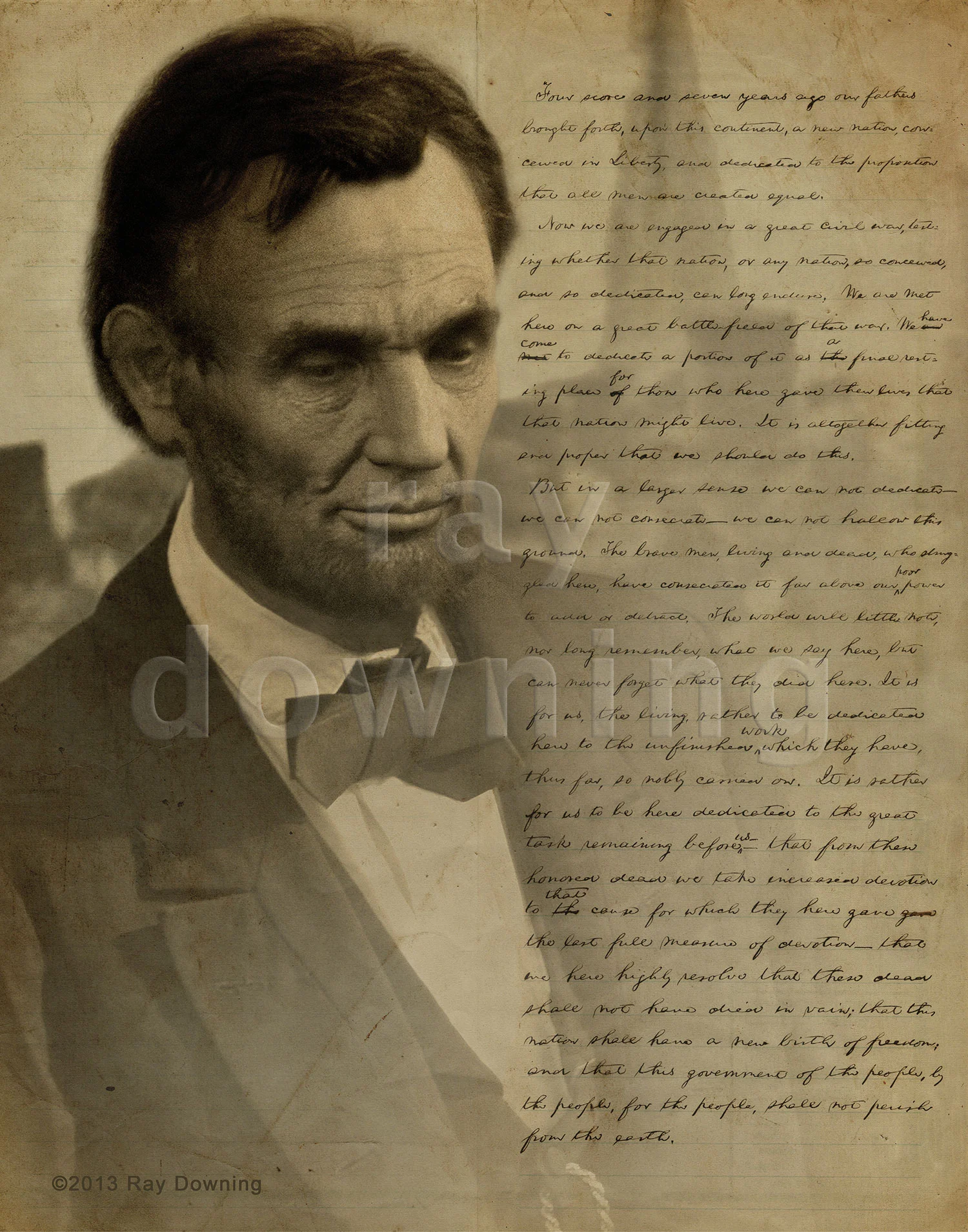

It’s a detective story played out in pixels and silver nitrates. We are obsessed with finding him because we want to connect with the man who redefined American democracy. We want to see the face of the guy who said "government of the people" while standing over the graves of the men who died for it.

Why the Quality is So Low

You’ve probably seen high-res photos of Lincoln taken in studios. Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner took stunning portraits of him where you can see every wrinkle and the texture of his mole.

So why is the photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg so grainy?

- Distance: The cameras were set back quite a way to capture the "magnitude" of the event.

- Movement: People were constantly shifting. It was a cold day; people were shivering or stamping their feet to stay warm.

- The Wet Plate Process: The light in November is weak. Weak light means longer exposure times. Longer exposure times mean more blur.

Essentially, the technology of 1863 was designed for still life, not for the chaotic movement of a political rally. We are lucky we have anything at all.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Scene

There’s this myth that the audience was stunned into silence by the brilliance of the speech. Or, conversely, that they hated it.

📖 Related: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

The photos tell a different story.

When you look at the wide shots of the crowd, you see people looking in every direction. Some are bored. Some are talking. Some are trying to get a better view. It was a long day of ceremonies. Edward Everett, the "main" speaker, talked for two hours before Lincoln even stood up.

By the time Lincoln got his turn, the crowd was exhausted.

The photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg captures that fatigue. It isn't a triumphant moment captured in a flash. It is a quiet, almost invisible moment in a crowded afternoon.

How to See the Photos Today

You don't need a secret pass to the National Archives to see these. They are digitized.

- The National Archives website hosts the Bachrach plate. You can download the high-resolution TIFF file and zoom in yourself. It’s a surreal experience to scroll through a 160-year-old crowd and suddenly find the President.

- The Library of Congress has the Gardner stereographs. These are the ones that spark the most debate among facial recognition experts.

- The Center for Civil War Photography often publishes "deep dives" into these plates, showing how they’ve been cleaned up using modern AI-upscaling—though you have to be careful with those, as AI likes to "hallucinate" details that aren't there.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs

If you want to truly appreciate the photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, don't just look at a thumbnail on Wikipedia.

Download the raw files. Go to the Library of Congress site and grab the uncompressed versions. Use a photo editor to play with the contrast. When you pull the shadows out of those old glass plates, faces emerge that haven't been "seen" in over a century.

Visit the spot. If you go to Gettysburg, stand at the Soldiers' National Cemetery. Look at where the platform was located (near the tan cottage, not where the big monument is now). Realizing how far the photographers were standing gives you a massive appreciation for how they managed to capture anything at all.

Check the provenance. If you find a "new" photo of Lincoln online, verify it through the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. There are tons of fakes and "misidentified" photos floating around Pinterest and X.

The hunt for the perfect photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg continues. Maybe there is a plate sitting in an attic in Pennsylvania right now, tucked in a dusty trunk, showing Lincoln mid-sentence with his arm raised. Until then, we have our blurs. And honestly, those blurs are enough to remind us that history was made by real, tired, mud-covered people.