If you look at a digital map of Manhattan today, it’s all right angles and predictable grids. Efficient. Boring, honestly. But pull up a high-resolution scan of an old New York city map from, say, 1776 or 1850, and you start to realize the city we walk through is basically a ghost story written in stone and asphalt.

Most people think the grid was always there. It wasn’t.

Before the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 flattened the island, New York was a chaotic mess of hills, swamps, and trout streams. It looked more like a wild countryside than a global metropole. When you study these old documents, you aren't just looking at dusty paper; you're looking at a version of the world that was systematically erased to make room for real estate speculation.

The Island That Was Flattened

The Ratzen Map of 1767 is a personal favorite for many historians. It shows a tiny, huddled version of the city at the southern tip of the island. Everything north of what is now Grand Street was just farms and estates. You see names like "Delancey" and "Stuyvesant" not as subway stops, but as actual pieces of dirt owned by real families.

The topography is the wildest part.

Manhattan used to be incredibly hilly. We’re talking steep climbs and deep valleys. The word "Manhattan" likely comes from the Munsee Lenape word Mannahatta, often translated as "island of many hills." If you look at an old New York city map from the 18th century, you see "Mount Pleasant" or "Bunker Hill." Where did they go?

They were shoveled into the valleys.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The city government literally decapitated the landscape. They took the dirt from the hills and dumped it into the marshes and ponds to create flat, sellable lots. Collect Pond, which was a massive freshwater body near where the courthouses in Lower Manhattan sit today, became so polluted by nearby tanneries that the city just filled it in. They used the dirt from the nearby Bayard’s Mount. Now, it’s just solid ground, but the buildings there have suffered from structural sinking issues for over a century because, well, you can't just delete a lake and expect the earth to forget.

Why the 1811 Grid Was Actually a Math Problem

John Randel Jr. is a name you should know if you’re into this stuff. He was the surveyor who spent years walking every inch of the island to lay out the 1811 grid. He had to deal with angry landowners who didn't want their orchards sliced in half by "10th Avenue."

His maps are masterpieces of precision.

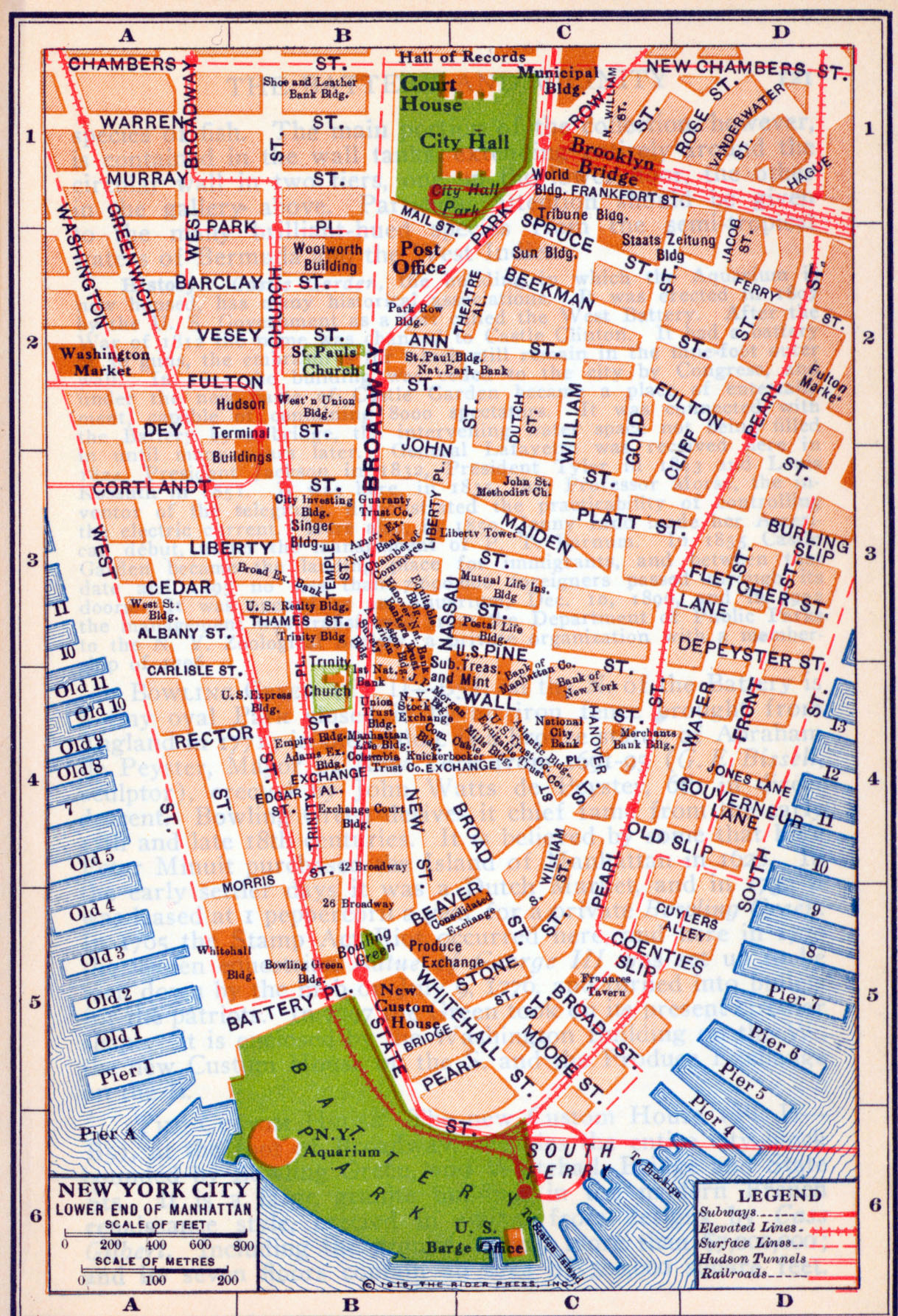

But here’s the thing: the grid was designed for economy, not beauty. The planners wanted "straight-sided and right-angled houses" because they were cheaper to build and easier to sell. It was a giant spreadsheet applied to the earth. When you look at an old New York city map from the mid-1800s, you can see the "Old Post Road" or "Bloomingdale Road" cutting weird, jagged diagonals across the emerging grid. Eventually, most of those paths were paved over.

Only Broadway survived.

Broadway is the ultimate rebel. It follows an ancient Wickquasgeck trail that ignores the grid entirely. It’s the only reason we have places like Union Square or Times Square. Those "squares" are actually just awkward triangles created because a pre-colonial path refused to align with a 19th-century math equation.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

The Mystery of the "Made Land"

If you’re standing at the South Street Seaport or Battery Park City, you aren't standing on the original island of Manhattan. You’re standing on trash, sunken ships, and excavated rock.

An old New York city map from the British occupation era shows the shoreline way further inland than it is now. Pearl Street used to be on the water. That’s why it’s called Pearl Street—the shores were covered in oyster shells. Over 400 years, New Yorkers have been "extending" the island.

- Battery Park City: Built entirely from the dirt excavated during the construction of the original World Trade Center.

- The East River Drive: Much of it sits on the rubble of bombed-out London buildings from WWII, brought over as ballast in ships.

- The World Financial Center: It's literally sitting on fill.

Looking at the Vielé Map of 1865 is the best way to see this. Egbert Vielé was a sanitary engineer who mapped the original waterways of Manhattan before they were buried. It’s often called the "Dead Map" because it shows where the water still wants to flow. If you’re a developer today, you still consult the Vielé map. Why? Because if you dig a basement where a stream used to be, your basement is going to flood. The water never left; it just went underground.

Reading the Map for Reality, Not Navigation

You've probably seen those beautiful, colorful lithographs from the late 1800s. The "birds-eye views." These weren't always accurate. They were often promotional pieces—basically 19th-century Instagram filters.

Real estate developers commissioned them to make the city look cleaner and more orderly than it actually was. They’d leave out the slaughterhouses and the cramped tenements of the Five Points. They’d emphasize the green trees and the majestic masts of the sailing ships.

To find the truth, you have to look at the insurance maps, like those produced by the Sanborn Map Company. These weren't for tourists. They were for fire insurance underwriters. They show every single building, what it was made of (brick or wood), where the windows were, and even what was being manufactured inside.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

If you find an old New York city map from Sanborn, you’re seeing the city’s skeleton. You see the tiny "rear tenements" where the poorest immigrants lived, hidden behind the nicer buildings on the street. You see the density that made New York both a miracle and a nightmare.

How to Use This Knowledge Today

Don't just look at these maps on a screen. If you're in the city, take a digital copy of the 1865 Vielé map or the 1811 Randel survey and go for a walk.

- Find the "Steps": Go to the Upper West Side. Notice how some streets have weird stairs or sudden elevation changes? That’s where the grid hit a rock formation too stubborn to be blasted away.

- Look for the Curves: Any time a street in Manhattan curves, you’re likely looking at a ghost. In Greenwich Village, the grid breaks entirely because the neighborhood was already built up before the 1811 plan arrived. The residents basically told the city to get lost.

- Check the Basements: If you’re in a building in Lower Manhattan and there’s a constant hum of a sump pump, check an old New York city map. I bet you $50 there’s a "lost" stream running right under your feet.

The New York Public Library’s Map Division is the holy grail for this. They have a tool called "Chronological NYC" that lets you overlay old maps on top of Google Maps. It’s addictive. You can see the exact moment a farm became a block of brownstones.

Understanding these maps changes how you feel about the city. It stops being a static place and starts feeling like a living, breathing, and slightly scarred organism. The "old" city isn't gone; it’s just the foundation for everything we’ve built on top of it.

To truly explore this, your next move should be visiting the NYPL Digital Collections online. Search for "Sanborn Maps Manhattan" and zoom in on your own block. Look at the "made land" markings along the Hudson. You might find that your favorite coffee shop is sitting on what used to be a 17th-century pier or a Dutch orchard. Once you see the layers, you can never go back to seeing the city in just two dimensions.