Alexander the Great didn't just pick a random spot on the Mediterranean coast because he liked the view. He wanted a hub. He wanted a bridge between the Greek world and the ancient Nile. But if you're looking for an Alexandria map ancient egypt actually produced in real-time, you're going to be a bit disappointed. Most of what we "know" about the layout of this city comes from much later descriptions or underwater archaeology that’s literally been pulled from the mud over the last thirty years. It's a puzzle.

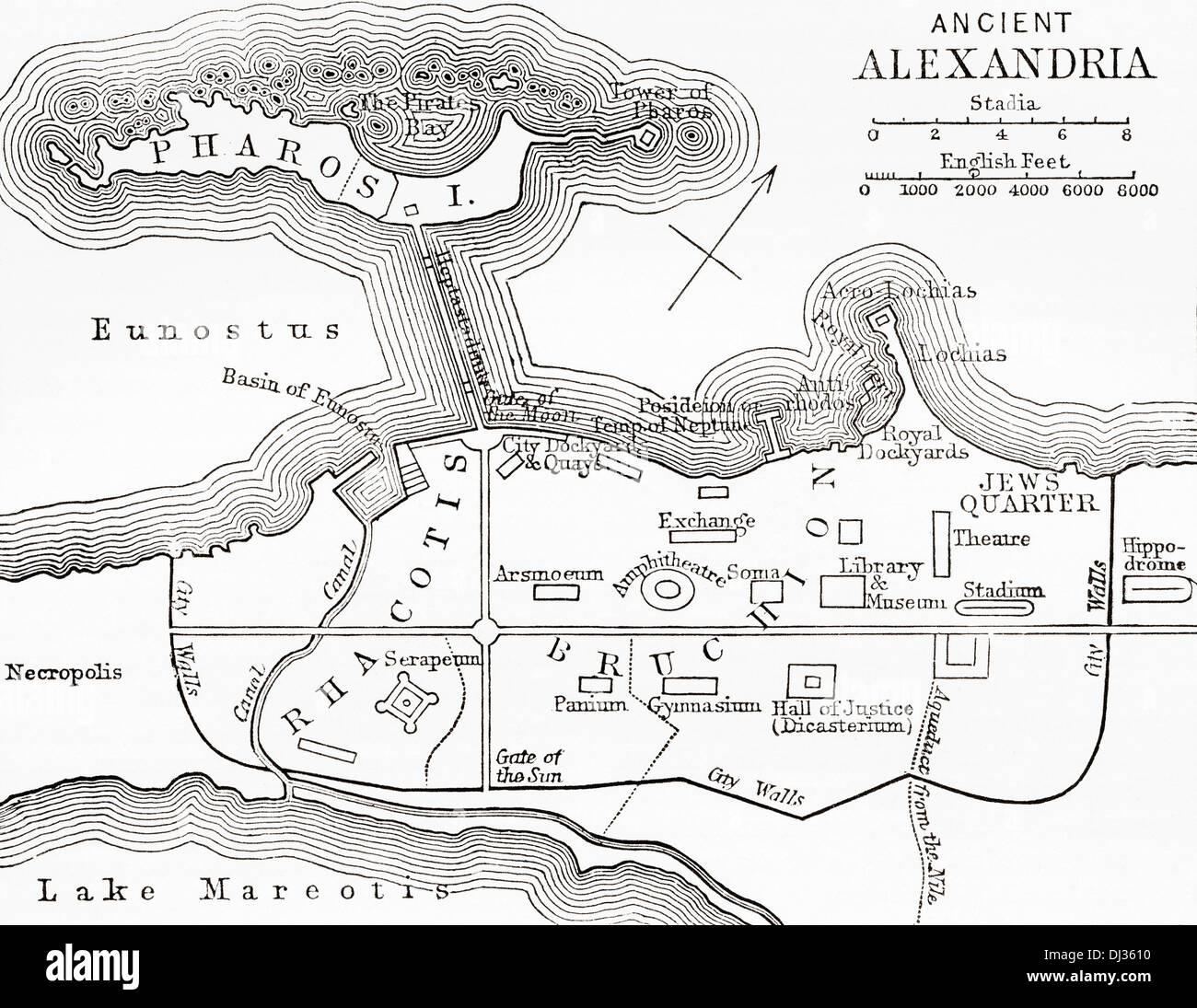

The city was designed by Dinocrates of Rhodes. He used a grid. It was basically the Manhattan of the ancient world. You had these massive, wide boulevards cutting through the city, which was pretty rare for the time. Most Egyptian cities were organic—messy, cramped, and built around the river’s whims. Alexandria was different. It was planned. It was a statement of power.

Why the Alexandria Map Ancient Egypt Experts Use Is Actually Underwater

When people search for a map of this place, they usually expect to see the Great Library or the Lighthouse of Alexandria (the Pharos) sitting neatly on a coastline. Reality is messier. Because of a combination of earthquakes, tsunamis, and land subsidence, a huge chunk of the royal quarter—the stuff of legends—is now at the bottom of the Mediterranean.

Frank Goddio and his team from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) are the ones who really changed the game here. Before their work in the late 90s and early 2000s, we were mostly guessing based on Strabo’s writings. Strabo was a Greek geographer who visited Alexandria around 25 BC. He described the "Heptastadion," a massive causeway that linked the island of Pharos to the mainland.

👉 See also: Finding the Train From Harvard to Chicago Schedule: What Actually Works

Think about that for a second. They built a seven-stadium-long bridge (about 1,200 meters) just to create two distinct harbors. This wasn't just a city; it was an engineering marvel.

The Grid That Defined an Empire

The "Canopic Way" was the main artery. It ran east to west. If you stood there in 300 BC, you’d see a street roughly 30 meters wide. That’s huge even by modern standards. It wasn't just for foot traffic; it was for parades, for moving troops, and for showing off the sheer wealth of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Most maps you’ll find today divide the city into five districts, named after the first five letters of the Greek alphabet: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon.

- Alpha was where the royal palaces sat.

- Delta was traditionally the Jewish quarter, one of the largest in the ancient world.

- Epsilon housed the native Egyptians.

This segregation tells you a lot about the social climate. It was a "melting pot," sure, but the layers didn't always mix well. The Greeks were the elite. The Egyptians, despite being in their own country, were often treated as second-class citizens in Alexander’s namesake city.

The Mystery of the Soma and the Great Library

Here is where the Alexandria map ancient egypt enthusiasts get frustrated. We know where the general "Royal Quarter" was, but we don't know exactly where Alexander the Great is buried. The "Soma" or "Sema" was the tomb of Alexander.

✨ Don't miss: Why a bear fights man for salmon: What actually happens when the food chain breaks

Every famous Roman you can think of—Julius Caesar, Augustus, Hadrian—visited it. Then, suddenly, it vanished from the records. Some think it’s under the Nabi Daniel Mosque. Others think it’s in the Latin Cemetery. Some even argue it was destroyed during the riots in the late 3rd century AD.

And the Library? Same problem. It wasn't one single building that "burned down" in one go, despite what the movies tell you. It was a series of collections. It likely sat near the Museion in the palaces. When you look at a reconstruction map, that cluster of buildings in the northeast is the brain of the ancient world. It's gone. All of it.

Canopus and Thonis-Heracleion: The Gatekeepers

You can't talk about the map of Alexandria without mentioning its neighbors. Before Alexandria was even a thought, Thonis-Heracleion was the primary port of entry for Egypt. It sat at the mouth of the Canopic branch of the Nile.

When Alexander built his city, Thonis-Heracleion eventually faded and sank. Goddio’s team found it under 30 feet of water. They found 64 ships, 700 anchors, and gold coins. This tells us the Alexandria map ancient egypt researchers use is actually part of a larger maritime complex. Alexandria wasn't an island; it was the center of a massive naval network that controlled the entire Mediterranean grain trade.

How to Read a Ptolemaic Map Today

If you’re trying to visualize this, start with the coastline. It’s shifted. The modern city of Alexandria is built directly on top of the ancient one. That’s why we can’t just dig a hole and find the Library.

The "Corniche" in modern Alexandria roughly follows the ancient coastline, but the old Royal Quarter is mostly submerged in the Eastern Harbor. If you go there today, you can see the Qaitbay Citadel. That fortress was built in the 15th century using the fallen stones of the Pharos lighthouse.

It’s literally a map made of recycled history.

The Realities of Land Subsidence

Why did the city sink? It wasn't just one "Day After Tomorrow" event. It was "soil liquefaction." Basically, the weight of the massive stone buildings on the silty Nile delta soil, combined with earthquakes, caused the ground to behave like a liquid. The buildings didn't just fall over; they slid into the sea.

This preserved them perfectly. The statues found underwater are in better condition than the ones left on land because they weren't weathered by wind or looted for building materials.

Practical Steps for History Buffs and Travelers

If you are actually looking to study or visit the remains of this ancient layout, don't just look at paper maps.

- Check the CEAlex (Centre d'Études Alexandrines) archives. They have the most accurate topographical data based on modern excavations. Jean-Yves Empereur, the founder, has done more for the land-based map of Alexandria than almost anyone.

- Visit the Kom el-Dikka site. This is one of the few places where you can actually see the ancient city grid on land. It has a Roman theater and a residential complex. It gives you a sense of the scale.

- Look at the underwater topography. Research the "Portus Magnus." This isn't just about pretty statues; it's about the shape of the seafloor, which reveals where the docks and warehouses once stood.

- Use the "Tabula Peutingeriana." This is a medieval copy of a Roman map. It shows Alexandria as a major hub with its distinct lighthouse symbol. It’s one of the few "period" maps that shows how the Romans visualized the city’s importance.

The truth is, the Alexandria map ancient egypt left for us is a ghost. We are still drawing the lines. Every time a diver pulls a sphinx out of the harbor, the map changes. It’s a living document. We know the boulevards were wide, the palaces were opulent, and the lighthouse guided the world, but the specifics are still buried under meters of salt and silt.

Instead of looking for a definitive, static image, focus on the reconstructions by IEASM. They represent the current gold standard of what the city actually looked like before the sea took it back.

To understand the layout of ancient Alexandria, you have to look at the intersection of Greek urban planning and Egyptian geography. The city was a grid forced upon a shifting, watery landscape. It was brilliant, but it was also precarious. If you want to see the "real" map, you have to look down—into the water of the Eastern Harbor and beneath the foundations of the modern city’s bustling streets.