It is huge. Like, really huge. Most people looking for the Pacific Ocean on a map for the first time are usually stunned by the sheer blue void that dominates the paper. It covers about 63 million square miles. That’s more than all the Earth's land masses combined. Think about that for a second. You could take every continent—Africa, Asia, both Americas, even tiny Antarctica—and drop them into the Pacific basin. You’d still have room left over for another Africa.

Most of us grew up with the "Atlantic-centric" view of the world. In this version, Europe and Africa are in the middle, and the Pacific is chopped in half, relegated to the far left and right edges. It makes the world feel smaller. It makes the ocean look like a border rather than a centerpiece. But if you flip the map or look at a "Pacific-centered" projection often used in Japan or Australia, everything changes. The world suddenly looks like a water planet.

Why the Pacific Ocean on a Map Isn't Always Where You Expect

Cartography is basically a big lie we all agreed on. Since the Earth is a sphere (sorry, flat-earthers) and a map is flat, you have to stretch things. This is where the Mercator projection messes with our heads. On a standard classroom map, the Pacific looks wide at the equator but weirdly pinched toward the poles.

If you're hunting for the Pacific Ocean on a map, your eyes probably go to the space between Asia and the Americas. But depending on the projection, the scale is often wildly misleading. On a Mercator map, Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger. This same distortion happens to the Pacific. It makes the crossing from San Francisco to Tokyo look like a straight line, when ships actually follow a curved "Great Circle" route that arcs way up near Alaska.

There’s also the issue of the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch." You won't find it labeled on a standard topographical map, but it's there. It’s not a solid island of trash you can walk on—it’s more like a cloudy soup of microplastics trapped by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. When people look at a map, they see pristine blue. Scientists like Captain Charles Moore, who discovered the patch, see a plastic-clogged engine.

🔗 Read more: Sheraton Grand Nashville Downtown: The Honest Truth About Staying Here

The Ring of Fire and the Hidden Mountains

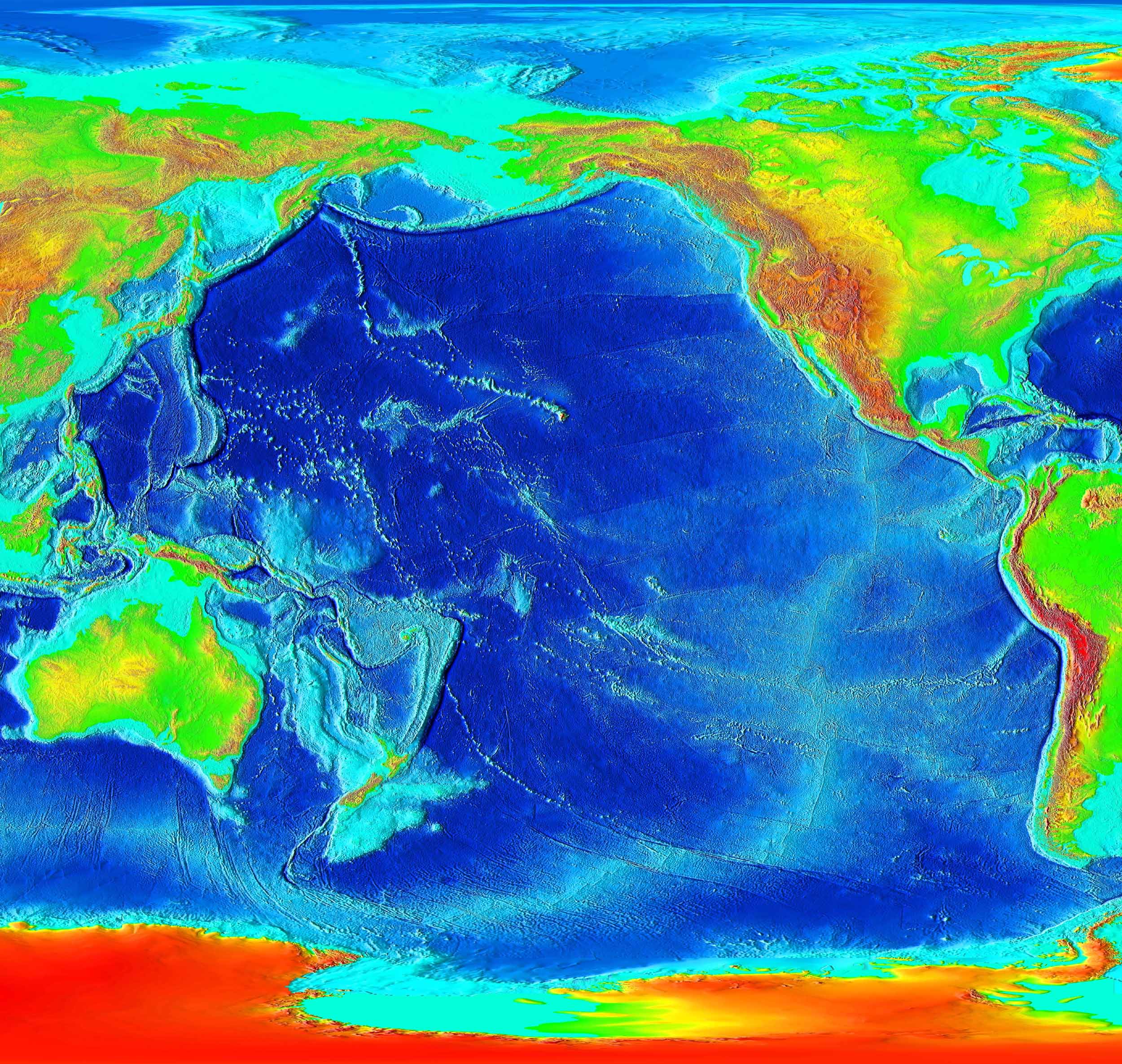

Look at a physical map of the Pacific. Not just a political one with country names, but one that shows bathymetry—the underwater topography. You’ll see a giant horseshoe shape tracing the edges. That’s the Ring of Fire. It’s where about 90% of the world's earthquakes happen.

If you could drain the water, the Pacific would be the most jagged, violent-looking place on Earth. You have the Mariana Trench near Guam, plunging down about 36,000 feet. If you dropped Mount Everest into it, the peak would still be over a mile underwater. Then you have the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain. These aren't just islands; they are the tops of massive volcanoes that have been slowly moving over a "hotspot" in the Earth's crust for millions of years.

Mapping this is a nightmare. Satellite altimetry is how we do it now. Satellites measure the height of the ocean surface, which actually bulges and dips depending on the gravity of the mountains on the seafloor below.

The Weirdness of the International Date Line

One of the most confusing things about spotting the Pacific Ocean on a map is that jagged line running down the middle. The International Date Line. It’s not a straight line because various island nations didn't want to be split into two different days.

💡 You might also like: Seminole Hard Rock Tampa: What Most People Get Wrong

Kiribati is the best example. They used to be split by the line, which made doing business nearly impossible because half the country was always in "tomorrow." In 1995, they moved the line way to the east. Now, on a map, it looks like a giant hammerhead shark sticking out into the ocean. This makes the Pacific the only place on Earth where you can sail for an hour and technically travel through time.

It’s easy to forget how isolated these points are. Look at Point Nemo. It’s the "Pole of Inaccessibility." It’s the spot in the Pacific furthest from any land. It is so remote that the closest humans to you are often the astronauts on the International Space Station when they fly overhead. On a map, Point Nemo is just a coordinate in a vast blue desert, but it’s where space agencies purposefully crash old satellites because there’s nothing there to hit.

Navigating the "Blue Continent"

Polynesian navigators didn't need a paper map. They used "stick charts" made of coconut fibers and shells to represent wave patterns and island locations. To them, the Pacific wasn't a barrier. It was a highway.

When we look at the Pacific Ocean on a map today, we see it through the lens of 18th-century explorers like James Cook. He was the one who mapped the coastline of Australia and New Zealand for the West. But his maps were tools of empire. They ignored the indigenous knowledge that had already mapped these waters mentally for thousands of years.

📖 Related: Sani Club Kassandra Halkidiki: Why This Resort Is Actually Different From the Rest

- The North Pacific: Dominated by the Kuroshio Current, bringing warm water toward Japan.

- The South Pacific: Home to the roaring forties, winds that make sailing treacherous but fast.

- The Central Pacific: A graveyard of coral atolls that are barely feet above sea level.

Climate change is literally rewriting the map here. As sea levels rise, atolls in the Marshall Islands or Tuvalu are shrinking. The "map" of the Pacific is not a static thing; it's a receding shoreline.

Practical Ways to Explore the Pacific via Digital Maps

If you want to actually see the Pacific in a way that makes sense, stop using flat maps. Use a globe or a digital tool like Google Earth. Spin it until you can’t see any land. That is the true scale of this ocean.

- Switch to Satellite View: Look for the deep navy blue areas; those are the trenches. The lighter teal areas are coral reefs and shallow shelves.

- Check the Currents: Use a site like "Earth Nullschool" to see real-time wind and ocean currents. It makes the Pacific look alive, like a swirling marble.

- Historical Overlays: Look up "The David Rumsey Map Collection." You can overlay 19th-century maps of the Pacific over modern ones to see how our understanding of the islands has changed.

The Pacific is basically the lungs of the planet. It regulates our weather. It absorbs a massive amount of CO2. When you find the Pacific Ocean on a map, you aren't just looking at water; you're looking at the primary engine of Earth's climate. Don't let the flat paper fool you. It's much deeper than it looks.

To truly understand the Pacific's scale, try this: open a digital map and measure the distance between Brisbane, Australia, and Santiago, Chile. It's roughly 7,000 miles. Then compare that to the width of the entire Atlantic. You'll realize the Pacific is a different beast entirely. Use bathymetric maps to identify the major ridges, as these dictate everything from fishing rights to where tsunamis might travel after an earthquake. Awareness of the "Ring of Fire" boundaries is also essential for anyone planning travel or business in the Pacific Rim.