You're sitting there staring at a chemical formula. Maybe it’s something simple like $NaCl$, or maybe it’s a terrifying polyatomic ion like $Cr_2O_7^{2-}$. You need to figure out where the electrons are hanging out. That’s essentially all you're doing when finding the oxidation number. It's a bookkeeping trick. Chemists use it to track electron flow during reactions, specifically redox reactions. If you don’t get this right, balancing equations becomes a nightmare. Honestly, it’s the difference between passing your midterms and staring blankly at a Scantron.

Oxidation numbers aren't "real" charges in the way an ion has a charge. They are imaginary. We pretend every bond is 100% ionic just to see who would "win" the electrons if they stopped sharing. It’s a bit cynical, really. We assume the more electronegative atom just steals everything.

The Ground Rules You Can't Ignore

Before you start doing math, you have to know the "Golden Rules." These aren't suggestions. They are the laws of the chemical land.

First, any element in its free state—meaning it’s just chillin' by itself—has an oxidation number of zero. It doesn’t matter if it’s a single atom of $Fe$ or a molecule like $H_2$ or $P_4$. If it's not combined with a different element, nobody is winning or losing. It's a tie. Zero.

Second, for monoatomic ions, the oxidation number is just the charge. If you see $Ca^{2+}$, the oxidation number is $+2$. Easy. But things get weird when we talk about Oxygen.

The Oxygen and Hydrogen Exceptions

Oxygen is almost always $-2$. It's a greedy element. It wants those electrons. But sometimes it loses. In peroxides like $H_2O_2$, Oxygen is actually $-1$. And if it’s paired with Fluorine (the only element more electronegative than Oxygen), it can even be positive. But let's be real—unless you’re in an advanced inorganic lab, it’s usually $-2$.

Hydrogen is usually $+1$. However, if it’s bonded to a metal (forming a hydride like $LiH$), it flips to $-1$. Metals are less electronegative than Hydrogen, so Hydrogen finally gets to be the bully and take the electron.

👉 See also: Amazon Kindle Colorsoft: Why the First Color E-Reader From Amazon Is Actually Worth the Wait

How to Find the Oxidation Number in Compounds

Let’s actually do some work. The main thing to remember is the sum. For a neutral compound, the sum of all oxidation numbers must be zero. If you have a polyatomic ion, the sum must equal the charge of that ion.

Step-by-Step with Potassium Permanganate ($KMnO_4$)

This is a classic. You’ve probably seen this purple stuff in a lab. We want to find the oxidation number for Manganese ($Mn$).

- Potassium ($K$) is in Group 1. It’s always $+1$.

- Oxygen is usually $-2$. We have four of them. So, $4 \times -2 = -8$.

- The whole thing is neutral.

So the math is: $(+1) + Mn + (-8) = 0$.

$Mn - 7 = 0$.

$Mn = +7$.

That’s a high oxidation state. It means Manganese has "lost" seven electrons in this arrangement. This makes $KMnO_4$ a powerful oxidizing agent. It is desperate to get those electrons back, which is why it reacts so violently with glycerin or other fuels.

Why Everyone Messes Up Polyatomic Ions

People forget the charge. They see $SO_4^{2-}$ and try to make it equal zero. Don't do that.

In the sulfate ion, Oxygen is $-2$. Four oxygens give us $-8$.

The total charge is $-2$.

So, $S + (-8) = -2$.

Add 8 to both sides. $S = +6$.

✨ Don't miss: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

If you had set it to zero, you’d get $+8$, which is impossible for Sulfur. Sulfur only has six valence electrons to give. You can't give what you don't have. This is a great way to double-check your work. If your answer is higher than the element's group number, you've probably made a mistake or forgot the ion's charge.

The Nuance of Fractional Oxidation Numbers

Can an oxidation number be a fraction? Yes. It feels wrong, but it happens. Take $Fe_3O_4$, also known as magnetite.

Oxygen is $-2$. Four of them make $-8$.

To balance this, the three Irons must total $+8$.

$3x = 8$.

$x = +8/3$.

Does an iron atom actually have 2.66 electrons missing? No. In reality, magnetite is a "mixed-valence" compound. It’s actually a mix of $FeO$ and $Fe_2O_3$. Some irons are $+2$, and some are $+3$. The $+8/3$ is just an average. It’s a shortcut for the bookkeeping, but it reflects a more complex physical reality where different atoms of the same element in a molecule hold different charges.

Common Pitfalls and Misconceptions

One major mistake is confusing formal charge with oxidation number. They are not the same thing. Formal charge assumes electrons are shared equally. Oxidation number assumes the more electronegative atom takes them all.

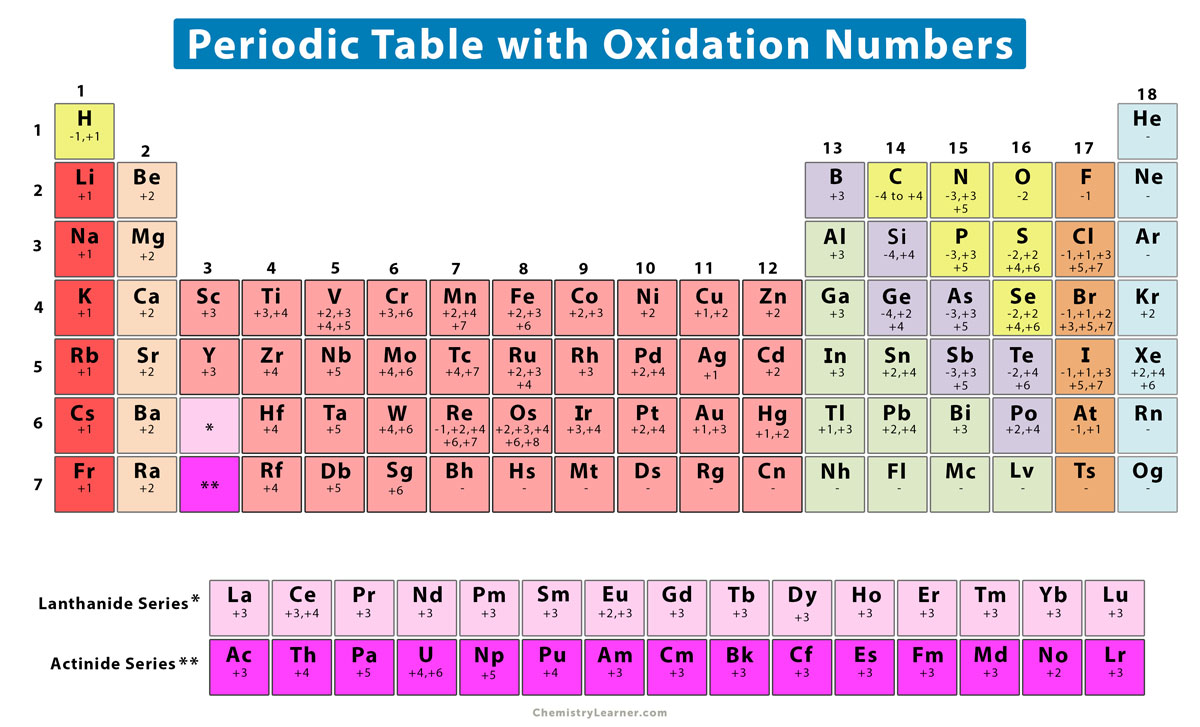

Another trap? Transition metals. They are the wild cards. They can have multiple oxidation states. Iron can be $+2$ or $+3$. Manganese can be anything from $+2$ to $+7$. You cannot just "know" their number by looking at the periodic table. You have to solve for them using the elements around them (like Oxygen, Chlorine, or Hydrogen) that have fixed rules.

🔗 Read more: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

Why Electronegativity is the Secret Key

If you ever get stuck and forget the rules, look at a Pauling Scale. Linus Pauling, a two-time Nobel laureate, developed this to quantify how badly an atom wants electrons. Fluorine is the king at 4.0. Cesium is at the bottom. When you're finding the oxidation number, you are basically just following the hierarchy of electronegativity.

Real-World Applications

Why do we care? Aside from passing a test.

Battery technology is entirely based on these numbers. When you charge your phone, you are forcing a "reduction"—lowering the oxidation number of Lithium by giving it electrons. When you use your phone, the Lithium is "oxidized," and those electrons flow through your phone's circuits to power your TikTok scrolling.

Environmental science relies on this too. Chromium-6 ($Cr^{+6}$) is highly toxic and carcinogenic (think Erin Brockovich). Chromium-3 ($Cr^{+3}$), however, is an essential nutrient in small amounts. Knowing how to find and change these numbers is literally a matter of public safety.

Summary of Actionable Steps

Stop guessing. Follow this flow every time you see a molecule.

First, check if it’s an element by itself. If it is, you're done. It's zero.

Second, look for the "sure things." Group 1 is $+1$. Group 2 is $+2$. Fluorine is $-1$.

Third, assign Oxygen its $-2$ and Hydrogen its $+1$. Watch out for those rare peroxides or hydrides, but don't overthink it unless the problem looks suspicious.

Fourth, set up your algebraic equation.

$Sum = Total Charge$.

Solve for the unknown.

If you end up with an oxidation number that is way higher than the valence electrons available for that atom, go back. You likely missed a charge on the ion or swapped a plus for a minus. Practice with $Cr_2O_7^{2-}$. If you can get $+6$ for Chromium, you’ve mastered the basics.

Go through your textbook or a worksheet and apply this to ten different compounds. Start with neutrals, then move to ions. By the fifth one, you won't even need to write the equation down. You'll just see the numbers in your head.