Look at any standard map. You see it right there—that lonely point at the top of the world where all the lines of longitude meet in a tidy little knot. It looks solid. Permanent. But if you actually flew a plane to that exact coordinate, you wouldn't find a flag sticking out of the ground. You'd find shifting ice and dark, freezing water.

The North Pole on the world map is basically a cartographic ghost.

Honestly, maps lie to us. They have to. Trying to flatten a 3D sphere onto a 2D sheet of paper is like trying to flatten an orange peel without tearing it; things get stretched and weird. Because of this, the way we visualize the top of our planet is riddled with misconceptions that have stuck around since the days of Mercator.

The Great Map Distortion: Why the Top Looks Massive

Ever noticed how Greenland looks about the same size as Africa on some maps? That’s the Mercator projection messing with your head. Gerardus Mercator designed his map in 1569 for sailors, and it was great for navigation because it kept local directions accurate. But it fails miserably at showing true size.

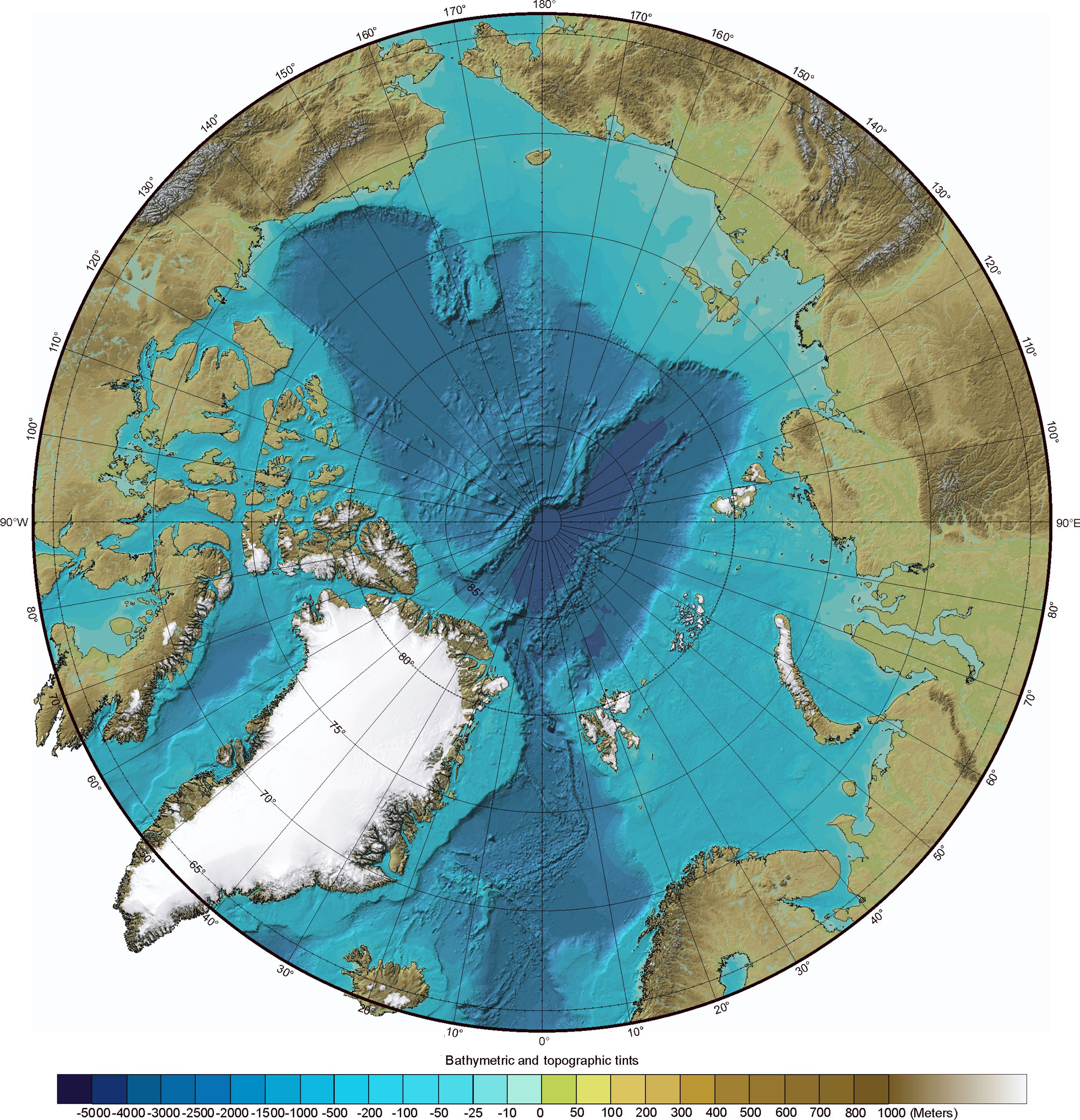

The closer you get to the North Pole on the world map, the more the landmasses are stretched horizontally. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. This distortion makes the Arctic look like a vast, sprawling continent. It isn't. While the South Pole sits on a massive landmass covered in ice (Antarctica), the North Pole is just a frozen lid on top of an ocean.

If you look at a Polar Projection—where you’re looking straight down at the Earth from above—the perspective changes entirely. You realize the Arctic is actually a Mediterranean of the north, a small ocean squeezed between Russia, Canada, Greenland, and Norway.

Geographic vs. Magnetic: Two Different Poles

We need to talk about the fact that there isn't just one North Pole. This trips people up all the time.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

- The Geographic North Pole: This is the "True North" you see on the North Pole on the world map. It’s the fixed point where the Earth’s axis of rotation meets the surface. It stays put.

- The Magnetic North Pole: This is where your compass points. It’s currently wandering toward Siberia at a rate of about 34 miles per year.

Scientists like Dr. Arnaud Chulliat from the University of Colorado Boulder have noted that this magnetic shift is happening so fast that navigation systems, including those in your smartphone, have to be updated more frequently than they used to be. If you followed a compass to the North Pole today, you'd end up hundreds of miles away from the spot marked on the map.

The Vanishing Act: Mapping an Ice-Only World

Mapping the North Pole is a nightmare for cartographers because the "land" is constantly moving. Most of the Arctic ice is sea ice, meaning it floats. It’s not tethered to the seabed.

If you stood at the Geographic North Pole, you’d be standing on ice about 6 to 10 feet thick. Beneath you? More than 13,000 feet of water. And because that ice is drifting, if you stood still for a day, you’d probably wake up a few miles away from where you started. How do you map that?

Usually, maps just color the whole area white. But as climate change accelerates, that white patch is shrinking. Since 1979, the Arctic has lost about 40% of its summer sea ice extent. We are rapidly approaching a time when a North Pole on the world map in September might show nothing but blue water.

Territorial Disputes and the Lomonosov Ridge

Because there’s no land, no one technically "owns" the North Pole. But that hasn't stopped countries from trying to claim the seabed underneath it.

Russia, Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), and Norway are all in a bit of a geopolitical tug-of-war. In 2007, a Russian expedition actually used a submersible to plant a titanium flag on the seabed, 4,000 meters below the North Pole. It was a bold move, kinda like a "dibs" on the potential oil and gas reserves.

✨ Don't miss: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

The central argument often revolves around the Lomonosov Ridge. It’s an underwater mountain range that crosses the Arctic Ocean. Russia argues it’s an extension of their continental shelf. Denmark says it belongs to Greenland. It’s a messy legal battle that involves the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

How to Actually "See" the North Pole Today

If you want to find the North Pole on the world map through a lens of modern tech, Google Maps or Apple Maps will show you a grainy, white-blotched area. This is because satellites don't often fly directly over the poles due to their orbital paths. Most of what you see is a composite of different images stitched together.

For a more accurate look, you have to turn to specialized tools:

- NSIDC (National Snow and Ice Data Center): They provide daily updates on ice concentration.

- NASA Worldview: This lets you see near real-time satellite imagery of the Arctic.

- Bathymetric Maps: These ignore the ice and show the fascinating landscape of the ocean floor, including the Gakkel Ridge, the deepest mid-ocean ridge in the world.

The Human Element: Who Actually Goes There?

While it looks desolate on a map, humans are all over the place near the Pole. You’ve got the Barneo Ice Camp, a temporary Russian base that’s rebuilt every April on a drifting ice floe for tourists and scientists. Then there are the nuclear submarines. During the Cold War, the Arctic was a playground for subs hiding under the ice. In 1958, the USS Nautilus became the first vessel to reach the Geographic North Pole, traveling entirely underwater.

Nowadays, you can actually book a trip on a nuclear-powered icebreaker like the 50 Let Pobedy. It’ll crunch through meters of ice to get you to 90 degrees North. It’s pricey—we’re talking $30,000 plus—but it’s the only way to see the "map" come to life.

Why the "Top" of the Map is Arbitrary

Here is a fun fact: there is no physical reason why the North Pole is at the top of the map. It’s a convention.

🔗 Read more: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Ancient Egyptian maps often put South at the top because the Nile flows North, and "up" meant upstream. Early Christian maps put East at the top because they believed Eden was in the East. It wasn’t until the Age of Discovery and the rise of the compass that North became the standard "up."

If you flipped your North Pole on the world map to the bottom, the geography would be exactly the same, but your brain would likely struggle to process it. It shows how much map-making is about culture, not just science.

The Reality of Living Near the Pole

The closest permanently inhabited place to the North Pole is Alert, in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It’s about 500 miles away. The people there live in a world of "Polar Night"—where the sun doesn't rise for months—and "Midnight Sun," where it never sets.

When you look at the North Pole on a flat map, you don't feel that cycle. You don't feel the fact that "East" and "West" cease to exist at that point. If you’re standing at the Pole, every direction you turn is South. That’s a level of geographical weirdness that a paper map just can’t convey.

Practical Ways to Understand Arctic Geography

If you're trying to get a real handle on how the North Pole fits into our world, stop relying on the rectangular maps hanging on classroom walls. They are tools for specific jobs, but they fail at giving you a sense of scale.

- Use a physical globe. It’s the only way to see how close Russia and North America actually are across the pole.

- Look at Great Circle routes. This explains why flights from New York to Hong Kong fly over the Arctic. It’s the shortest distance, even if it looks like a long curve on a flat map.

- Check the Arctic Council updates. This is where the eight nations with territory in the Arctic Circle (plus indigenous groups) try to manage the region's future.

The North Pole isn't just a point on a map. It’s a shifting, melting, politically charged piece of the planet that is currently undergoing the most rapid change of any environment on Earth. Understanding where it is—and where it isn't—is the first step in realizing how connected we are to that cold, dark point at the top of the world.

Actionable Next Steps

- Switch your perspective: Open Google Earth (not Google Maps) and rotate the view until you are looking directly down at the Arctic. This eliminates the Mercator distortion and shows you the "Mediterranean of the North" layout.

- Track the drift: Visit the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) website to see the "Sea Ice Index." Compare the current ice extent to the 30-year average to see how the "white space" on your map is physically changing.

- Check your compass: Use a "Magnetic Declination" calculator online to see how far "Magnetic North" is from "True North" at your current location. This helps you understand why the North Pole on the world map requires constant data updates for your GPS to work.