You’ve seen it a thousand times. You open a standard map of the world, and there it is—or rather, there it isn't. Most people trying to find the north pole in world map layouts end up staring at a smeared, white blob at the top of a rectangle, or they realize the map just... stops. It’s frustrating. It's also a massive lie told by geometry.

The North Pole isn't a landmass. That’s the first thing to get straight. Unlike Antarctica, which is a continent buried under ice, the North Pole is just a point in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. If you stood there, you'd be standing on drifting sea ice about 6 to 10 feet thick, with two miles of freezing water underneath your boots. Because it's water, it doesn't always play nice with cartography.

Mapping a sphere onto a flat sheet of paper is basically impossible without breaking something. Imagine peeling an orange and trying to flatten the skin into a perfect square. You can’t do it without tearing the peel or stretching it until it looks unrecognizable. This is the "map projection" problem, and the North Pole is its biggest victim.

The Mercator Problem: Why the North Pole Looks Huge (or Missing)

Most of us grew up with the Mercator projection. It’s the one hanging in every classroom. It’s great for ships because it keeps compass directions straight, but it’s a total disaster for size and the poles. On a Mercator map, the further you get from the equator, the more things stretch.

The North Pole technically can't even be shown on a standard Mercator map. To represent the actual pole, the map would have to be infinitely tall. Usually, mapmakers just cut the map off at about 82 or 85 degrees north. So, when you look for the north pole in world map formats like this, you’re usually just seeing the very top of Greenland or the Svalbard archipelago, while the actual pole is off the edge of the paper, somewhere near the ceiling.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

It makes Greenland look as big as Africa. In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger than Greenland. This distortion makes the Arctic look like a vast, endless frontier of white, when it’s actually a relatively contained ocean basin surrounded by Russia, Canada, Norway, and the U.S. (via Alaska).

Finding a Better View: The Polar Azimuthal Projection

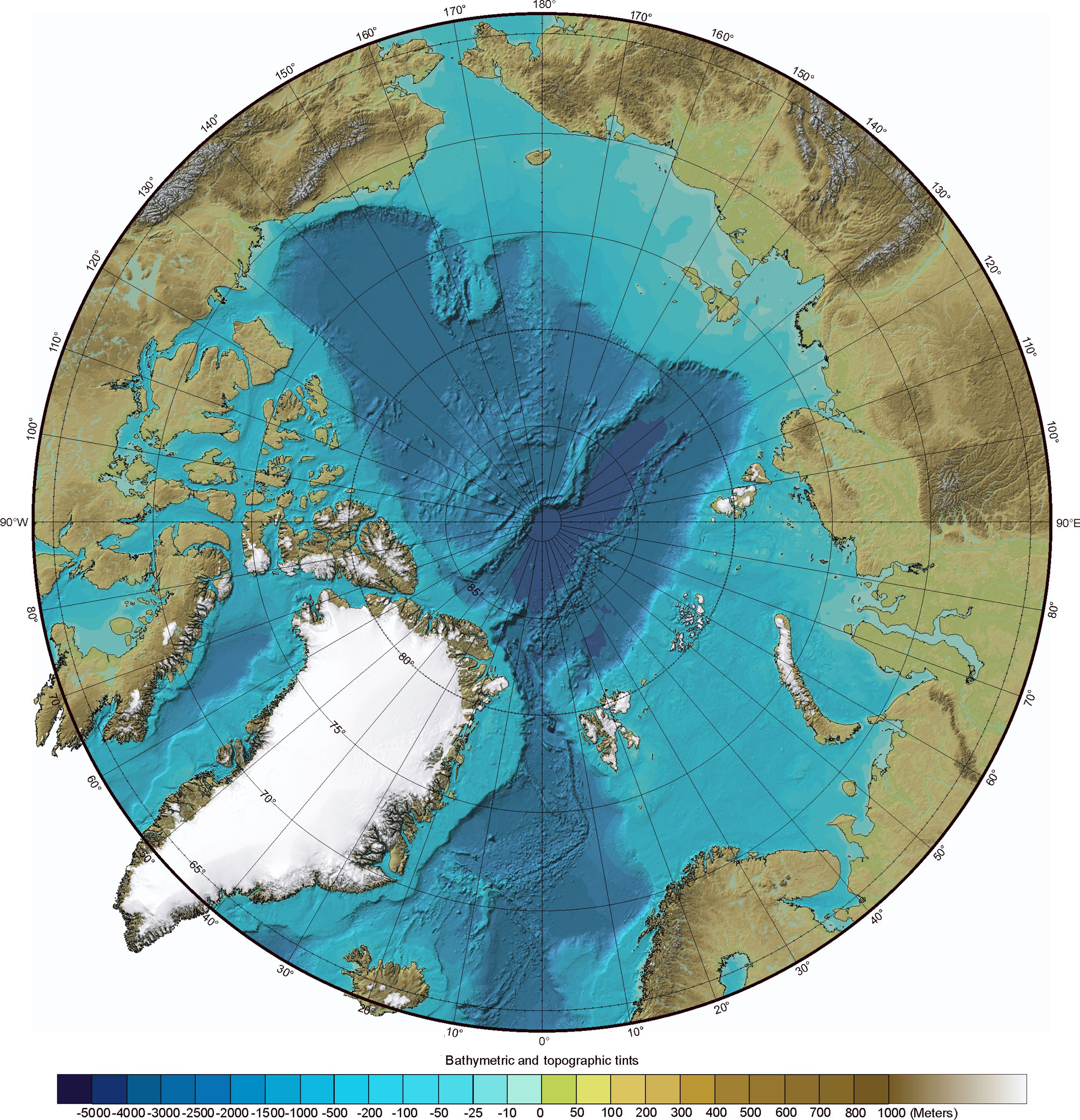

If you actually want to see what's going on at the top of the world, you have to ditch the rectangles. You need a "top-down" view. This is called a Polar Azimuthal Equidistant projection. It’s the view you see on the United Nations flag.

In this version, the North Pole is the dead center of the circle. Everything else radiates outward. It’s the only way to understand how close Russia and North America actually are. During the Cold War, this was the map that mattered. While schoolkids looked at Mercator maps that made the USSR and the USA look like they were on opposite sides of the world, military planners were looking at polar maps, realizing that a bomber or a missile only had a relatively short hop across the Arctic ice to reach the other side.

Magnetic vs. Geographic: Which Pole are You Looking For?

Here is where it gets kinda trippy. There isn't just one North Pole.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

- The Geographic North Pole: This is the "True North." It’s the fixed point where the Earth's axis of rotation meets the surface. If you’re looking at a north pole in world map graphic, this is usually what the grid lines (meridians) are pointing to.

- The Magnetic North Pole: This is what your compass points to. It’s not fixed. It moves. In fact, it’s currently hauling tail away from the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia at a rate of about 34 miles per year.

If you bought a map ten years ago, the magnetic north pole marked on it is wrong today. Scientists at the British Geological Survey and the National Centers for Environmental Information have to update the World Magnetic Model every few years because the liquid iron in Earth's core shifts, dragging the magnetic field with it.

The Arctic is Shrinking, and the Maps are Changing

When you look at the North Pole on a map today, you're looking at a historical document. The "permanent" ice pack shown in white on most maps is no longer permanent. Since 1979, the Arctic has lost about 40% of its summer sea ice extent.

Cartographers are struggling with this. Do you shade the North Pole white to represent ice, even if that ice is gone for three months of the year? If you look at Google Maps or Apple Maps in satellite mode, the North Pole often looks like a messy patchwork of blue. This isn't because of a secret government cover-up; it's because satellites like the Landsat program often have "orbital holes." They don't fly directly over the pole every day, and stitching together moving ice floes into a seamless image is a nightmare.

Basically, the ice moves while the satellite is taking the picture. It's like trying to take a panoramic photo of a crowd of people running in different directions.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

How to Actually Locate the North Pole on Any Map

If you’re staring at a map and trying to find the exact spot, follow these steps:

- Find the 90th Parallel: Look for the latitude lines. The Equator is 0°. The North Pole is 90° North. If your map stops at 80°, you're not seeing the pole.

- Follow the Meridians: All the vertical lines (longitude) meet at the North Pole. If the lines are parallel and never touch (like on a Mercator), the pole is "at infinity."

- Look for the "Arctic Circle": This is the dotted line at roughly 66.5° N. Everything north of this line experiences at least one day of 24-hour sunlight and one day of 24-hour darkness. The Pole is the center of this circle.

Honestly, the best way to see the North Pole is to use a globe. Digital tools like Google Earth are okay, but they still use "tiling" that gets wonky at the top. A physical globe is the only way to see the Arctic without the "Mercator stretch" making it look like a giant white monster.

The Realities of Modern Mapping

We’re getting better at this. New satellite missions like ICESat-2 use lasers—actual lasers—to measure the height of the ice at the North Pole within a few centimeters. This data is being used to create the most accurate maps of the Arctic we've ever had. But these aren't the maps you'll find in a travel brochure. They are complex, data-heavy visualizations used by climate scientists at places like the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

For the average person, the north pole in world map views remains a bit of a mythic space. It’s a place that’s defined more by what’s missing (land) than what’s there.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the North Pole Digitally

If you want to move beyond the distorted rectangle maps and see the North Pole as it really is, do this:

- Use NASA’s Worldview: Go to the NASA Worldview website. It lets you see daily satellite imagery. You can toggle "Arctic" as the base projection to see the pole from the top down without the distortion.

- Track the Magnetic Shift: Visit the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) website to see the "Wandering Pole" animation. It shows exactly where the magnetic pole has moved over the last hundred years.

- Check the Sea Ice Index: If you're looking at a map and it shows a solid white mass, verify it against the NSIDC's "Arctic Sea Ice News & Analysis." This shows you the real-time edge of the ice, which is usually hundreds of miles away from where older maps say it should be.

- Switch Projections in GIS: If you’re a student or a pro, stop using EPSG:3857 (Web Mercator) for anything involving the poles. Switch to a North Pole Stereographic projection (like EPSG:3413) to get an accurate shape and distance measurement.

Maps are tools, not perfect mirrors of reality. The North Pole is the ultimate proof of that. It’s a point that exists perfectly in our minds and our math, but refuses to stay still on a flat piece of paper.