You’re staring at a small square on the Periodic Table. It’s got a couple of letters, maybe a decimal point at the bottom, and a whole number at the top. It looks like a simple ID card for an atom, but honestly, it’s more like a coded map. If you know how to read it, you can basically tear an atom apart in your head. Finding the neutrons protons and electrons of an element isn't just some chore for chemistry class; it’s the key to understanding why some things explode in water while others just sit there for a billion years.

Most people get tripped up because they think atoms are static. They aren't. They’re buzzing, vibrating, and occasionally losing pieces of themselves. But let's get the basics down first.

The Atomic Number Is Your North Star

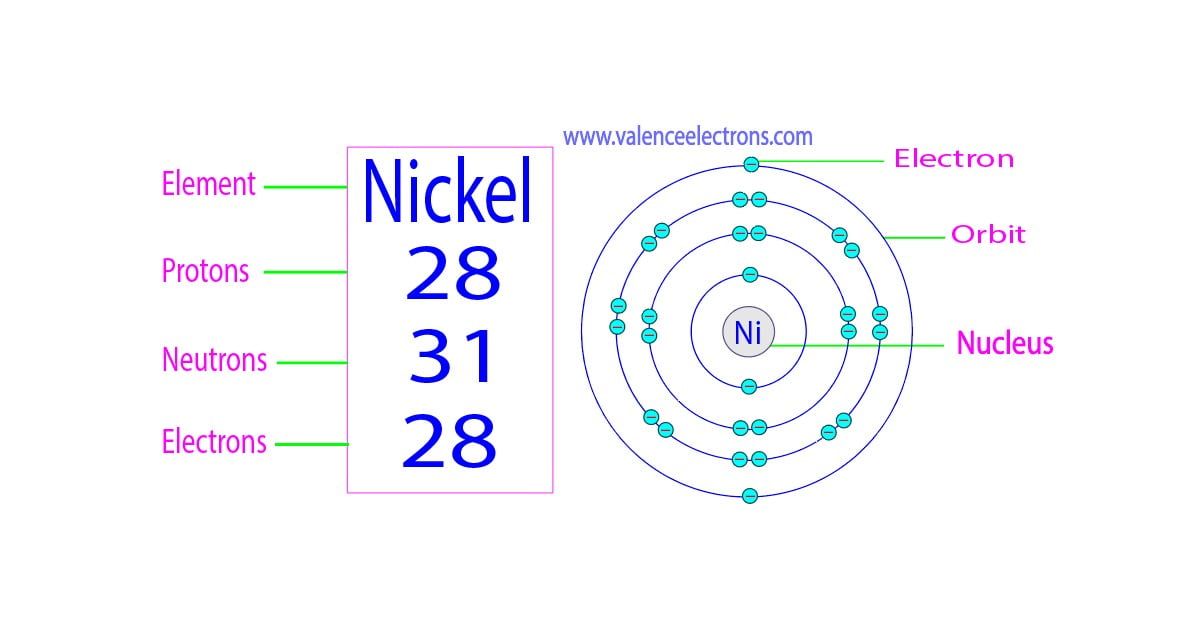

Look at the top of that square. That whole number? That's the Atomic Number. It is the most important number in chemistry because it defines the element's identity. If you change the number of protons, you change the element. Period.

Suppose you’re looking at Carbon. Its atomic number is 6. That means every single Carbon atom in existence—whether it’s in the diamond on a ring or the graphite in a pencil—has exactly 6 protons. If it had 7, it would be Nitrogen. If it had 5, it would be Boron. So, the rule is dead simple: The Atomic Number is the number of protons. No math required. Just look at the chart.

Now, what about the electrons? In a neutral atom—the kind you find on a standard chart—the number of electrons is identical to the number of protons. Why? Because nature loves balance. Protons have a positive charge. Electrons have a negative charge. To keep the atom from having a "mood swing" (an electrical charge), those two numbers have to match. So, for Carbon, you’ve got 6 protons and 6 electrons. Done.

The Neutron Problem: Why the Decimal Matters

This is where things get a bit messy. You’ve probably noticed that the number at the bottom of the square, the Atomic Mass, is usually a messy decimal. For Carbon, it’s 12.011. You can’t have 0.011 of a neutron. That’s not how physics works.

The reason that number is a decimal is that it’s an average. In the real world, elements come in different "flavors" called isotopes. Some Carbon atoms are light (Carbon-12), and some are slightly heavier (Carbon-14). The Periodic Table gives you the weighted average of everything found in nature.

To find the number of neutrons in the most common version of an element, you have to do a little rounding. Take that decimal and round it to the nearest whole number. This gives you the Mass Number.

The Simple Subtraction Formula

The nucleus is made of protons and neutrons. Together, they make up almost all the mass of the atom. Electrons are so light they basically don't count—kind of like trying to weigh a bowling ball and worrying about a speck of dust sitting on it.

The formula for finding the neutrons protons and electrons of an element is:

Mass Number - Atomic Number = Number of Neutrons.

Let’s try it with Gold ($Au$).

Its atomic number is 79. (79 protons).

Its atomic mass is 196.967.

Round 196.967 to 197.

$197 - 79 = 118$.

Gold has 118 neutrons.

👉 See also: Is the MacBook Air Sky Blue Actually Real? What You’re Likely Seeing Instead

What Happens When the Rules Break?

Honestly, the "neutral atom" is a bit of a lie we tell beginners. In the wild, atoms are constantly gaining or losing electrons. When they do, they become ions.

If an atom has a little plus sign next to it ($Na^+$), it means it lost an electron. It’s now "positive" because it has more protons than electrons. If it has a minus sign ($Cl^-$), it grabbed an extra electron from somewhere. To find the electrons in an ion, you start with the atomic number and then do the opposite of what the sign says. A $+1$ charge means you subtract an electron. A $-2$ charge means you add two.

Isotopes are the other "rule breaker." If a scientist tells you they are working with Uranium-235, they are giving you the Mass Number directly. You don't look at the decimal on the chart anymore. You just take that 235 and subtract Uranium’s atomic number (92).

$235 - 92 = 143$ neutrons.

If you used the "standard" mass from the table, you'd get a different number, and your nuclear reactor would probably have a very bad day.

A Quick Reference for Common Elements

Sometimes it helps to see how this looks in practice across different parts of the table.

For Oxygen ($O$):

Protons: 8 (Atomic number).

Electrons: 8 (Matches protons).

Neutrons: 16 (Mass) minus 8 = 8.

For Iron ($Fe$):

Protons: 26.

Electrons: 26.

Neutrons: 56 (Mass is 55.845, so round up) minus 26 = 30.

For Silver ($Ag$):

Protons: 47.

Electrons: 47.

Neutrons: 108 (Mass is 107.86) minus 47 = 61.

Notice a pattern? As atoms get heavier, they need way more neutrons to act as "glue" to keep all those positive protons from repelling each other. It’s a delicate balancing act of the strong nuclear force.

📖 Related: Why Atomic Bomb Explosion Photos Still Haunt Us Decades Later

Why Should You Actually Care?

It’s easy to think this is just academic fluff. But understanding the balance of these particles is how we have modern medicine. Radioactive isotopes—atoms with "too many" neutrons—are used in PET scans to find cancer. By tracking how many neutrons an element has, we can date ancient bones (Carbon-14 dating) or even determine where a piece of intercepted nuclear material came from.

If you’re trying to master this for a test or a project, don't overthink it. Most of the information is hidden in plain sight right there on the table. The protons are the ID. The electrons are the shadow of the protons. And the neutrons are just the remainder when you subtract the ID from the weight.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Atoms

- Get a High-Quality Periodic Table: Don't use a blurry one from a 20-year-old textbook. Use a dynamic one like Ptable where you can see how mass changes across isotopes.

- Always Identify the Atomic Number First: It’s your anchor. Everything else builds off that number.

- Check for Charges: If there is no symbol like $+$ or $-$, the electrons and protons are equal. If there is a charge, adjust the electron count only.

- Watch the Rounding: For general chemistry, rounding to the nearest whole number is standard. However, if you are doing high-level physics, you must use the specific mass of the isotope provided in the problem.

- Practice the "Big Three" Subtraction: Grab three random elements from the transition metals (the middle of the table) and calculate their neutrons. These are often the ones that catch people off guard because their masses aren't "clean" multiples of their atomic numbers.