If you’re staring at a digital atlas or a dusty paper map of East Asia, trying to find the Manchurian Plain on a map, you might realize it’s not always labeled with that specific name. Modern cartography usually calls it the Northeast China Plain. It’s massive. Seriously. We are talking about the largest plain in China, stretching across roughly 135,000 square miles. To put that in perspective, you could fit the entire state of New Mexico inside it and still have room for a few small European countries.

It’s a weirdly shaped area. It looks like a giant, tilted kidney bean squeezed between mountains. When you find it, you’ll see it’s guarded by the Greater Khingan Range to the west, the Lesser Khingan to the north, and the Changbai Mountains to the east. It’s basically a fertile bowl.

Most people think of China and immediately picture the yellow loess of the central plains or the jagged karst peaks of the south. But the Manchurian Plain is different. It’s deep, dark, and cold. If you’ve ever heard of "Black Soil" (Heitudi), this is where it lives. This soil is so rich it’s practically legendary, though it’s also disappearing at an alarming rate due to over-farming.

Where Exactly Is the Manchurian Plain on a Map?

Locating it is actually pretty simple once you know the landmarks. Look at the "rooster's head" of China—that’s the Northeast. The plain occupies the central part of that head. It spans three main provinces: Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. Occasionally, it spills a bit into Inner Mongolia.

The plain isn't just one flat pancake. It’s actually three smaller basins that grew into each other over millions of years. You’ve got the Liaohe Plain in the south, the Songnen Plain in the middle, and the Sanjiang Plain up in the northeast corner where the Amur, Songhua, and Ussuri rivers meet.

If you are looking at a physical map with elevation colors, look for the big green patch surrounded by browns and yellows. That’s your spot. It sits mostly below 650 feet (200 meters) above sea level. It feels low because the surrounding mountains are so imposing.

The Three Main Zones

The southern part, the Liaohe Plain, is where things get a bit more industrial. It drains into the Liaodong Bay. It’s warmer here. Not tropical, obviously, but you aren't going to get the "freeze your eyelashes off" temperatures you find further north in Harbin.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

Then there’s the Songnen Plain. This is the heartland. It’s drained by the Songhua and Nen rivers. If you see a map with a lot of blue veins zig-zagging through the green, you’re looking at the drainage system that makes this place the breadbasket of China.

Finally, the Sanjiang Plain. This used to be a massive wetland, nicknamed the "Great Northern Wilderness." Now, it’s mostly rice paddies. It’s right on the border with Russia. You can almost feel the Siberian wind just looking at it on a map.

Why Does This Patch of Land Matter So Much?

History isn't just about people; it's about dirt and geography. The Manchurian Plain has been a geopolitical tug-of-war for centuries. The Jurchens, the Manchus, the Mongols—they all used this space as a springboard.

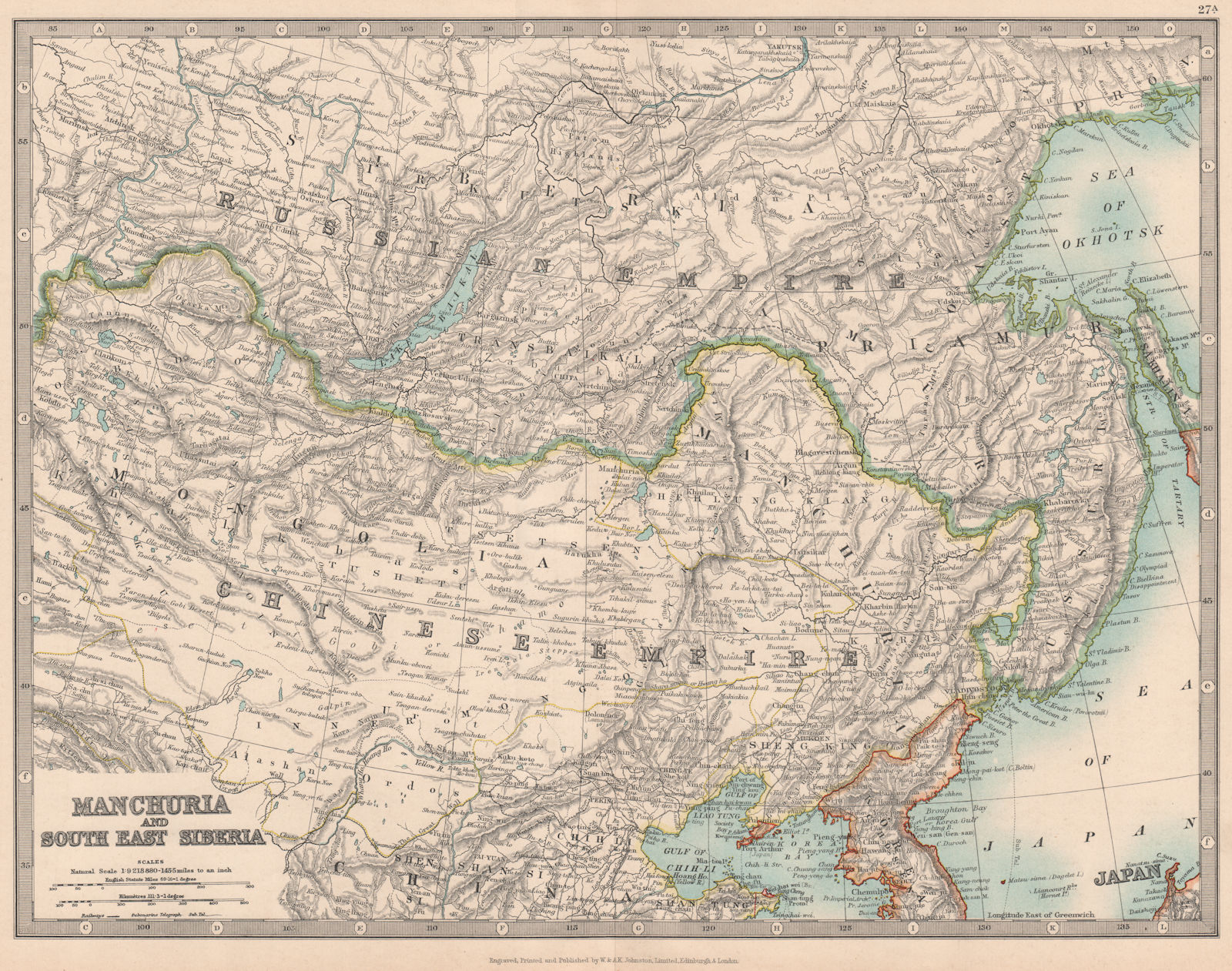

In the early 20th century, this was the "Flashpoint of Asia." The Russians wanted it for their railway to the Pacific. The Japanese wanted it for its coal, iron, and space. The Chinese needed it for, well, everything. When you look at the Manchurian Plain on a map from the 1930s, you’ll see it labeled as "Manchukuo," a puppet state established by Japan.

That era changed the landscape forever. The Japanese built a massive rail network that still forms the skeleton of the region’s infrastructure today. They turned the plain into an industrial powerhouse. Even now, cities like Shenyang and Changchun are heavy hitters in manufacturing, though they've struggled with the "Rust Belt" transition lately.

The Black Soil Crisis

We have to talk about the dirt. It sounds boring, but it’s critical. The Manchurian Plain is one of only four major black soil regions in the world. The others are in the Mississippi River Valley, the Pampas in Argentina, and the Ukraine-Russia region.

✨ Don't miss: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

This soil is organic-rich. It’s incredibly productive. But because of intensive farming since the 1950s, the layer of black earth is thinning. In some places, it has dropped from a meter deep to just 20 or 30 centimeters. Chinese scientists like Liu Xiaobing have been sounding the alarm for years. If the soil goes, the food security of a huge chunk of Asia goes with it.

How to Read the Topography

When you’re squinting at the Manchurian Plain on a map, pay attention to the river flow. Most rivers in the world flow south or east. In the northern part of this plain, they do some funky things because of the terrain. The Songhua River flows northwest before hooking back around.

- Check the borders: The Amur River (Heilong Jiang) marks the northern boundary with Russia.

- Spot the cities: Harbin is the northern hub, Changchun is in the middle, and Shenyang is the southern anchor.

- Look for the wetlands: The Zhalong Nature Reserve on the western edge is a massive stopover for red-crowned cranes. It’s one of the few places where the plain hasn't been completely turned into a cornfield.

The climate here is "Dwa" in the Köppen classification. That’s a fancy way of saying "Monsoon-influenced hot-summer humid continental." Basically, it’s a land of extremes. Summers are humid and surprisingly hot. Winters are long, dry, and brutally cold. This temperature swing is what helped create that rich soil over thousands of years as vegetation rotted slowly in the cold.

Misconceptions About the Region

A lot of people assume the Manchurian Plain is just a frozen wasteland because of its latitude. It's actually at the same latitude as Southern France or the Northern US. The reason it’s so cold is the Siberian High—a massive pressure system that dumps frigid air onto the plain all winter long.

Another mistake? Thinking it’s all agriculture. While it produces a staggering amount of corn, soy, and japonica rice, the plain is also a hub for the "Old Industrial Base." It was China's first real industrial center. If you visit, you’ll see massive steel mills and car factories (like the FAW Group in Changchun) sitting right next to endless fields of grain.

The "Wilderness" Myth

Is it still wild? Not really. Most of the original forest and steppe was cleared decades ago. However, the edges of the plain where it meets the mountains are still rugged. The Changbai Mountains to the east are home to the Siberian Tiger (though they are very rare) and the legendary Heaven Lake, a volcanic crater on the border with North Korea.

🔗 Read more: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

Actionable Tips for Navigating the Region

If you are actually planning to visit or study the area, don't just rely on a generic map of China. You need specific regional layouts.

For Travelers: If you’re going in winter, go to Harbin for the Ice and Snow Festival. It’s built on the banks of the Songhua River. But honestly, if you want to see the "Plain" in its glory, go in late summer. The corn is ten feet tall, and the scale of the landscape is overwhelming.

For Researchers: Use the term "Northeast China Plain" when searching for academic papers or GIS data. Most modern Chinese government data and international geological surveys have moved away from the term "Manchurian Plain" because of its colonial associations.

For Map Enthusiasts: Look for maps that highlight the "Liaohe-Songhua Divide." It’s a subtle rise in the land that determines whether water flows south to the Yellow Sea or north toward the Amur. It’s the invisible spine of the plain.

Understanding the Manchurian Plain on a map requires looking past the flat green space. You have to see the rivers that carved it, the mountains that protect it, and the black soil that makes it one of the most valuable pieces of real estate on the planet. It’s a landscape defined by its limits—limited by cold, limited by soil erosion, and limited by the heavy weight of 20th-century history.

To get a true sense of the scale, open Google Earth and zoom into the area between 40°N and 50°N latitude. Turn on the "historical imagery" layer if you can. You can literally watch the cities expand and the wetlands shrink over the last thirty years. It’s a vivid, slightly heartbreaking way to see geography in motion.

Start by identifying the three-way junction of the Sanjiang Plain. Once you find that triangle where the rivers meet the Russian border, the rest of the geography falls into place. You’ll see how the mountains cup the plain, creating a world within a world that looks unlike anywhere else in China.