Chemistry is basically just fancy cooking. Think about it. If you have ten slices of bread but only one slice of cheese, you aren't making five grilled cheese sandwiches. You’re making one. The cheese is the thing that stops the party. In the lab, we call that the limiting reagent.

It’s the most important concept in stoichiometry because it dictates exactly how much product you’re actually going to get at the end of a reaction. Most students—and honestly, plenty of professionals—get bogged down in the math and lose sight of what’s happening in the beaker. If you want to know how to work out limiting reagent problems every single time without pulling your hair out, you have to stop looking at the numbers as abstract symbols and start looking at them as ratios.

You’ve got a balanced equation. You’ve got some starting materials. Now, you need to figure out which one is going to run out first. It’s not always the one with the smallest mass. That’s the trap.

Why the Smallest Mass Isn't Always the Limiting Factor

A common mistake is assuming that if you have 5 grams of Substance A and 10 grams of Substance B, then A must be the limiting reagent. Wrong.

Chemistry doesn't care about grams. Atoms don't weigh the same. Imagine you’re trying to build bicycles. You have 50 pounds of tires and 40 pounds of frames. Because a frame weighs way more than a tire, those 40 pounds of frames might only be two units, while 50 pounds of tires could be dozens. You’ll run out of frames first despite them "weighing" almost as much as the tires.

To find the limiting reagent, you have to convert everything into moles. Moles are the "quantity" of the chemistry world.

The Step-by-Step Reality

First, you need a balanced chemical equation. If your equation isn't balanced, stop. Do not pass go. Everything that follows will be trash. A balanced equation tells you the recipe. For example, in the Haber process for making ammonia:

$$N_2 + 3H_2 \rightarrow 2NH_3$$

This tells us we need three molecules of hydrogen for every one molecule of nitrogen. It’s a 1:3 ratio. If you have equal amounts of both, you’re going to run out of hydrogen much faster.

How to Work Out Limiting Reagent: The Comparison Method

There are a couple of ways to do this, but the most "bulletproof" method involves calculating how much product each reactant could make if it were the boss.

- Convert your starting masses to moles. Use the molar mass from the periodic table.

- Pick one product. It doesn't matter which one if there are multiple.

- Do the stoichiometry. Calculate how many moles of that product you’d get from each reactant.

- Compare. The reactant that yields the smallest amount of product is your limiting reagent.

Let's look at a real-world scenario. Say you're reacting 25.0 grams of silver nitrate ($AgNO_3$) with 15.0 grams of sodium chloride ($NaCl$) to produce silver chloride.

$$AgNO_3 + NaCl \rightarrow AgCl + NaNO_3$$

First, we get the moles. $AgNO_3$ has a molar mass of about 169.87 g/mol. $NaCl$ is about 58.44 g/mol.

For $AgNO_3$:

$25.0 \text{ g} / 169.87 \text{ g/mol} = 0.147 \text{ moles}$.

✨ Don't miss: The Chemical Symbol of Lithium: Why Li Matters More Than You Think

For $NaCl$:

$15.0 \text{ g} / 58.44 \text{ g/mol} = 0.257 \text{ moles}$.

Since the ratio in the equation is 1:1, it’s pretty obvious here. The silver nitrate is going to run out first. It produces 0.147 moles of $AgCl$, whereas the salt could have produced 0.257 moles. The $AgNO_3$ is the limiting reagent.

The Ratio Shortcut (For the Confident)

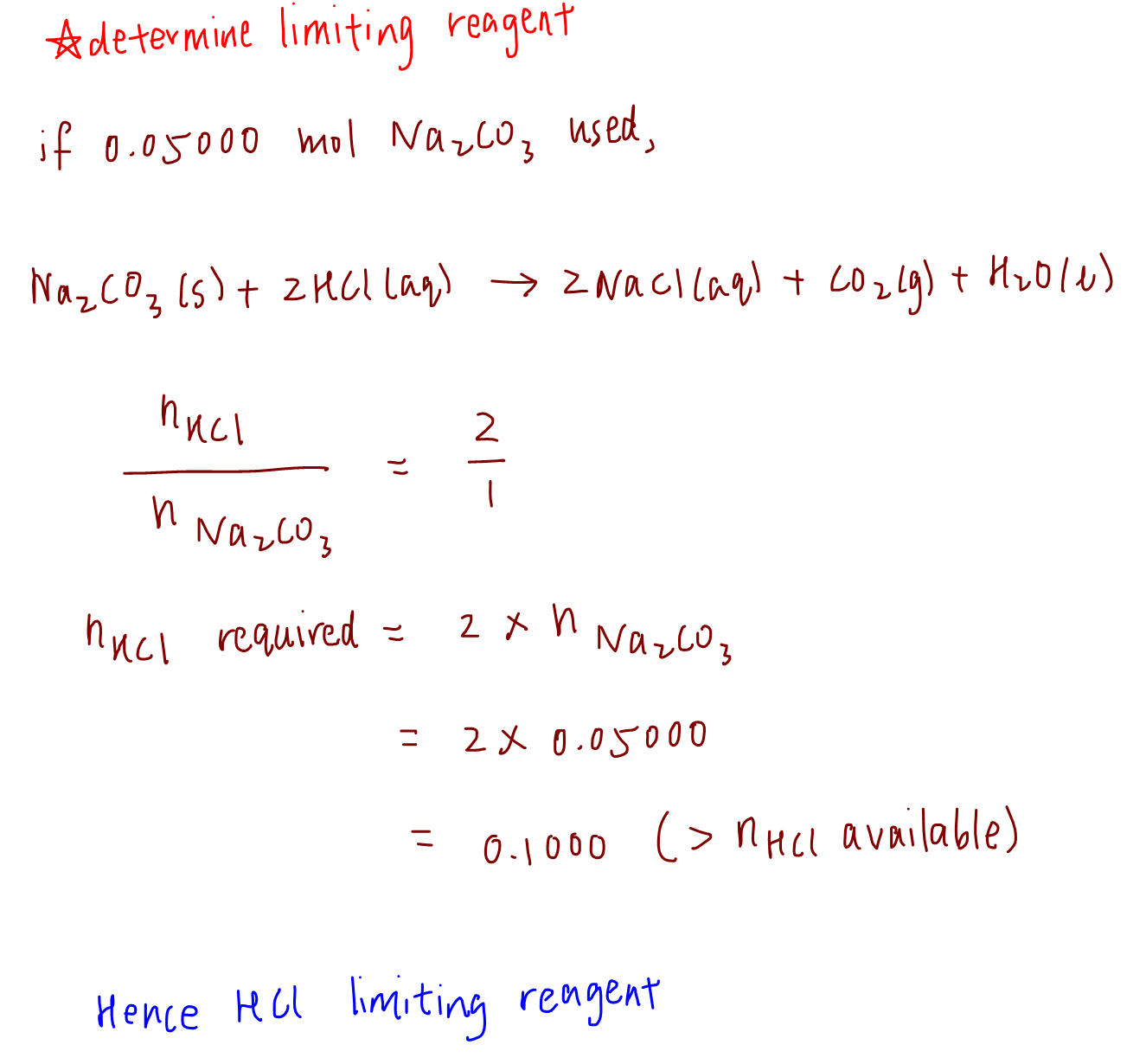

Sometimes you don't want to do the full calculation for the product. You just want to know what's going to hit the bottom of the jar first. You can take your moles of each reactant and divide them by their respective coefficients from the balanced equation.

- Reactant A: Moles / Coefficient A

- Reactant B: Moles / Coefficient B

The smaller number wins the "limiting" title. It’s quick. It’s dirty. It works.

Real-World Consequences in Industry

This isn't just for passing a Chem 101 quiz. In industrial chemical manufacturing, companies like BASF or Dow Chemical have to be obsessed with this. Why? Money.

If one of your reactants is incredibly expensive—let's say a palladium catalyst or a complex organic precursor—you want that to be your limiting reagent. You want to ensure every single molecule of the expensive stuff is used up. To do that, you flood the reaction with an "excess" of the cheaper reagent.

If you're making aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), you react salicylic acid with acetic anhydride. Salicylic acid is usually the one you want to limit because you don't want unreacted, needle-like crystals of it hanging around in your final product.

Misconceptions That Trip People Up

- "The limiting reagent is always the one with the smallest coefficient." Nope. The coefficient just tells you the ratio needed, not what you actually have in the beaker.

- "I can just use the mass ratio." Never. Mass is deceptive. Always go to moles.

- "The reaction stops immediately." In a textbook, yes. In real life, reactions slow down as the limiting reagent concentration drops. This is why "yield" is rarely 100%.

What About Excess Reagents?

Once you've figured out how to work out limiting reagent, the next question is always: "How much of the other stuff is left over?"

You take the moles of the limiting reagent and calculate how much of the excess reagent it actually used. Then subtract that from your starting amount. It’s like checking your bank account after a shopping spree. You started with $100, you spent $80 based on the price of the items (the limiting reagent's requirement), and you’re left with $20.

Nuance: Reversible Reactions

Life gets messy when reactions are reversible. In an equilibrium situation, the "limiting" concept is a bit more fluid because the reaction doesn't go to completion. However, for the vast majority of standard stoichiometry problems, you assume the reaction goes until someone runs out.

Practice Makes It Intuitive

If you're struggling, try the "Ice Cream Sandwich" analogy.

- 2 cookies + 1 scoop of ice cream = 1 sandwich.

- If you have 20 cookies and 7 scoops of ice cream, how many sandwiches?

- 20 cookies could make 10 sandwiches.

- 7 scoops could make 7 sandwiches.

- The ice cream is limiting. You'll have 6 cookies left over.

Actionable Next Steps for Mastery

To really nail this, don't just read about it. Do these three things right now:

- Grab a periodic table and find the molar masses for a common reaction, like combustion of propane ($C_3H_8 + 5O_2$).

- Pick two random masses (e.g., 50g of propane and 100g of oxygen) and run the "Product Comparison" method.

- Check your work by using the "Ratio Shortcut" (Moles / Coefficient). If both methods give you the same limiting reagent, you've got it.

Understanding the limiting reagent is the "aha!" moment in chemistry. Once you stop fearing the coefficients and start seeing them as requirements, the math stops being a hurdle and starts being a map.