You’re staring at a triangle. Not just any triangle, but a right-angled one, the kind with that little square in the corner that promises order in a chaotic world. You need to find the long side. The big one. The hypotenuse.

Most of us haven't touched a geometry textbook since high school, yet somehow, the need to compute hypotenuse lengths pops up when you're building a deck, coding a collision hitbox for a video game, or just trying to figure out if that new 65-inch TV will actually fit on your wall.

It's basically the most practical math you'll ever use. Honestly, it’s just the relationship between three lines, but people get weirdly intimidated by it. They remember a Greek guy named Pythagoras and some letters, then their brain just sort of fogs over. Let’s clear that up.

The Geometry of the Longest Side

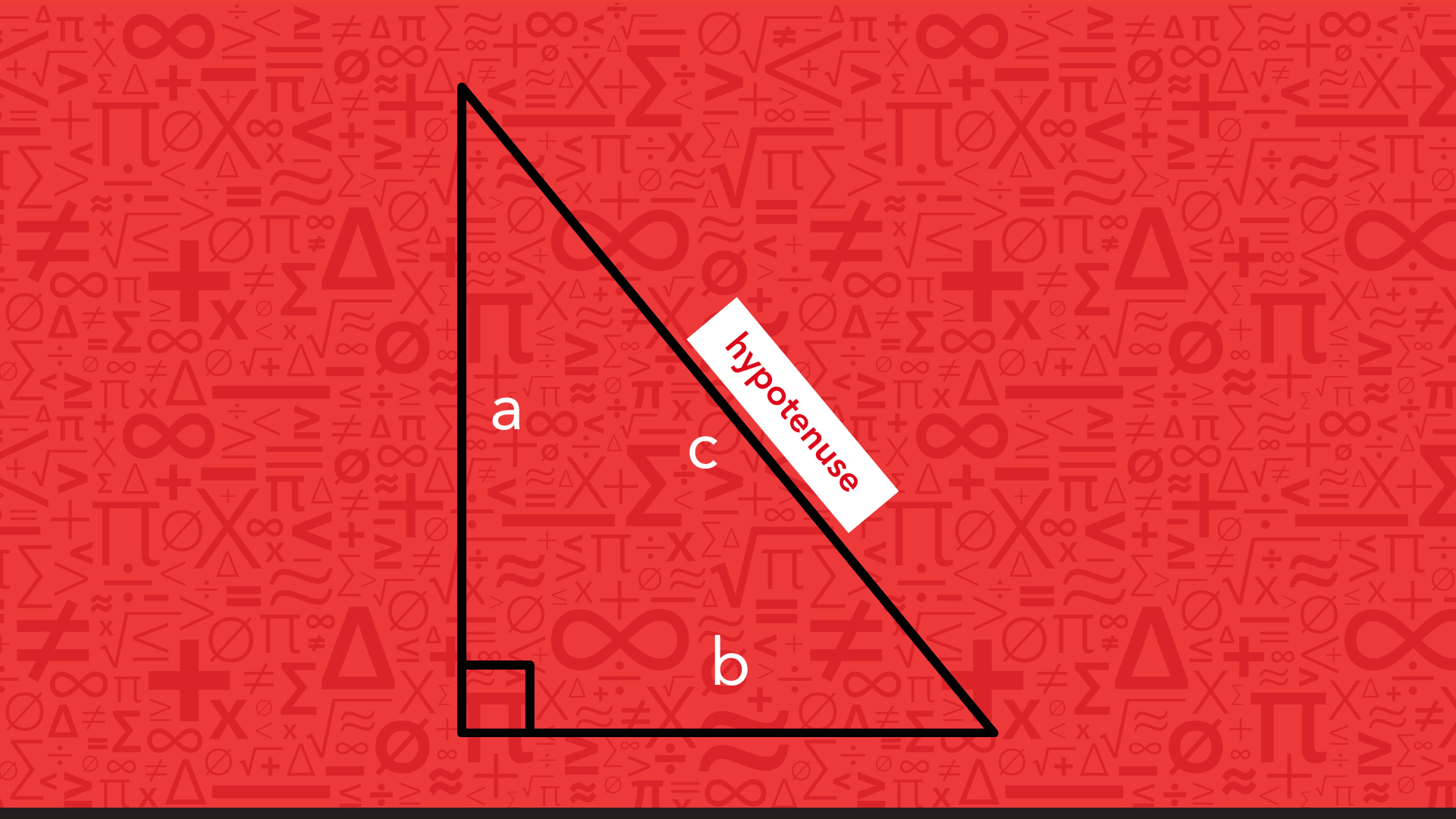

The hypotenuse is always the side opposite the 90-degree angle. Always. It’s the longest side because it’s opening up across from the widest jaw of the triangle. If you have a triangle where the hypotenuse isn't the longest side, you don’t have a right triangle—you have a drawing error.

To compute hypotenuse values, we rely on the Pythagorean theorem. It's a fundamental principle of Euclidean geometry. While we attribute it to Pythagoras, there's actually evidence from the Plimpton 322 Babylonian tablet that mathematicians were playing with these ratios over a thousand years before Pythagoras was even born. The Greeks just did the best marketing for it.

The math is simple:

$$a^2 + b^2 = c^2$$

In this equation, $a$ and $b$ are the "legs" (the shorter sides), and $c$ is the hypotenuse. You square the legs, add them together, and then find the square root of that sum to get $c$.

Why Your Brain Trips Over the Calculation

People usually mess up the order of operations. They’ll add $a$ and $b$ first and then try to square the result. That’s a disaster. If you have a side of 3 and a side of 4, adding them gets you 7. Squaring 7 gets you 49. But if you do it right—square 3 to get 9, square 4 to get 16, and add those—you get 25. The square root of 25 is 5.

See the difference? 7 is not 5. Your deck would be crooked.

Real-World Example: The TV Dilemma

Imagine you see a TV advertised by its diagonal—which is just a fancy word for the hypotenuse of the screen. If the screen is 20 inches tall and 35 inches wide, how big is that diagonal?

📖 Related: Who Made the Parachute: The Messy History of How We Learned to Fall

- Square the height: $20 \times 20 = 400$.

- Square the width: $35 \times 35 = 1225$.

- Sum them: $1625$.

- Root it: $\sqrt{1625} \approx 40.3$ inches.

Beyond Pythagoras: The Trigonometry Shortcut

Sometimes you don't know both legs. Maybe you only know one side and an angle. This is where people start sweating, but it’s actually faster if you have a calculator.

If you’re a developer working in Unity or Godot, or maybe you're just doing some high-level carpentry, you use Sine and Cosine. Specifically, if you have the "opposite" side (the one across from your known angle) and that angle ($\theta$), the formula to compute hypotenuse looks like this:

$$c = \frac{\text{opposite}}{\sin(\theta)}$$

Or, if you have the "adjacent" side (the one touching the angle):

$$c = \frac{\text{adjacent}}{\cos(\theta)}$$

It feels like overkill until you're trying to calculate the slope of a roof and you only have a protractor and a tape measure.

The Precision Trap

Don't get obsessed with infinite decimals. Unless you’re NASA landing a rover on Mars, you don’t need sixteen decimal places.

If you are using the Pythagorean theorem for a home DIY project, rounding to the nearest eighth of an inch is more than enough. In coding, floating-point errors can actually creep in if you're doing these calculations millions of times per second in a physics engine. Developers often use "Square Magnitude" comparisons instead of finding the actual hypotenuse just to save processing power. Why find the square root if you can just compare the squared values? It's a clever trick.

Common Pitfalls and Non-Euclidean Weirdness

The biggest mistake is trying to apply this to triangles that aren't "right." If that angle is 89 degrees or 91 degrees, the Pythagorean theorem is useless. You’d need the Law of Cosines for that, which is a whole different headache involving $a^2 + b^2 - 2ab \cos(C)$.

Also, keep in mind that this only works on a flat plane. If you’re calculating distances on a globe—like flight paths—the "straight line" is actually a curve. This is spherical geometry. On a sphere, the shortest distance between two points isn't a simple hypotenuse; it's a "Great Circle" distance. If you tried to use $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$ to navigate a ship across the Atlantic, you’d end up hundreds of miles off course.

Practical Next Steps

Ready to actually use this? Grab a tape measure and find a corner in your house. Measure 3 feet out on one wall and 4 feet out on the other. Mark both spots. Measure the diagonal between those two marks. If it’s exactly 5 feet, your walls are square. If it’s not, your house is slightly crooked—don't worry, most are.

🔗 Read more: How to Trim Music iMovie Without Losing Your Mind

To master this for more complex tasks, start by:

- Hard-coding a simple hypotenuse function in Python or Excel to automate your frequent measurements.

- Memorizing the "Pythagorean Triples" (3-4-5, 5-12-13, 8-15-17) to do mental checks on the fly.

- Checking your calculator mode; if you're using trig to find the hypotenuse, make sure you aren't in "Radians" when you mean to be in "Degrees."

The math isn't the hurdle. It's usually just the confidence to trust the formula. Square them, add them, root them. Done.