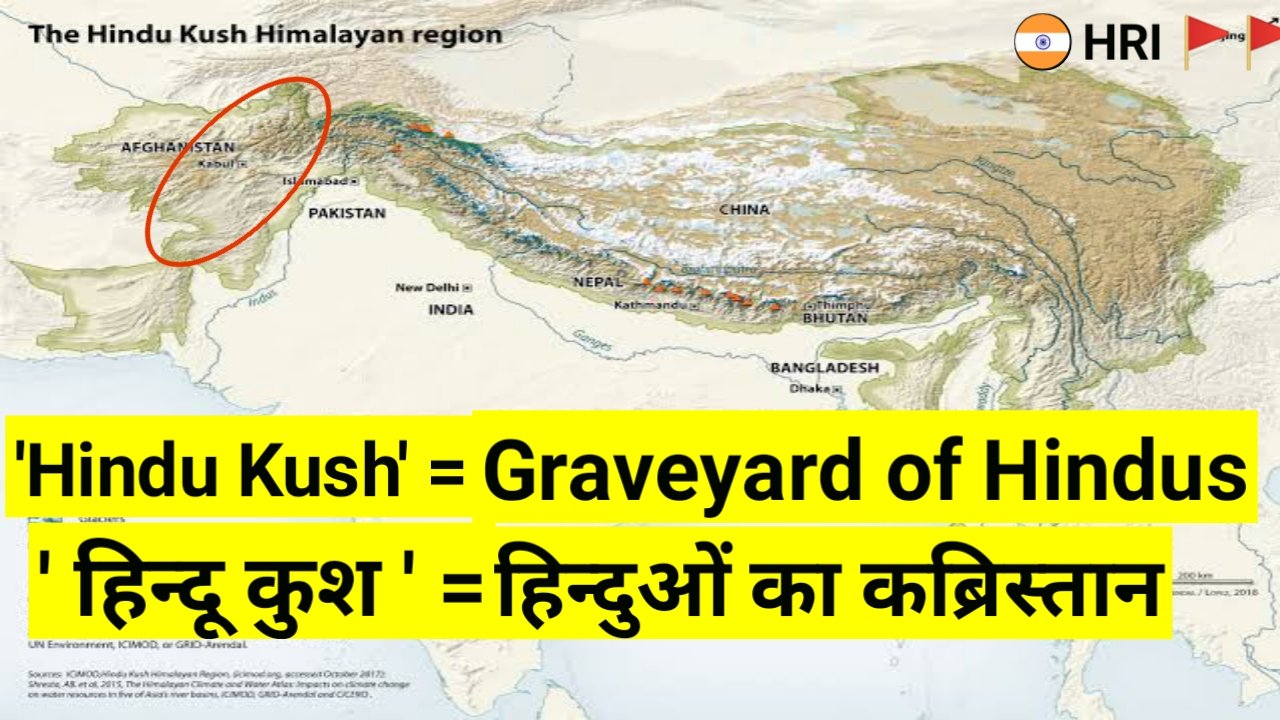

If you zoom out and look at a satellite view of Central Asia, you’ll see a massive, jagged scar of brown and white cutting across the landscape. That's the Hindu Kush. Most people know the name from history books or news reports about geopolitical shifts, but actually locating the Hindu Kush mountains on map reveals a much more complex story than just a simple mountain range. It’s a 500-mile-long (800 km) beast that stretches from the Pamir Knot in Tajikistan and China all the way down into central Afghanistan.

It's massive.

Honestly, it’s one of the most rugged places on the planet. Unlike the gentle rolling hills of the Appalachians or even the structured peaks of the Alps, the Hindu Kush is a chaotic mess of high-altitude desert and permanent glaciers. It basically divides the world. To the north, you have the Amu Darya valley and the plains of Central Asia. To the south, the Indus River valley and the heat of the Indian subcontinent.

🔗 Read more: San Francisco Earthquake Info: What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Big One

Where Exactly Are the Hindu Kush Mountains on Map?

When you’re trying to find the Hindu Kush mountains on map, start your eyes at the "Pamir Knot." This is a geographical cluster where several of the world's highest ranges—the Himalayas, the Karakorams, the Kunluns, and the Pamirs—all collide like a slow-motion car crash of tectonic plates. From this point, the Hindu Kush branches off toward the southwest.

The eastern section is the most intense. We’re talking about peaks that regularly top 20,000 feet. Tirich Mir is the big one here, standing at 25,230 feet (7,708 meters) in Pakistan's Chitral District. It’s the highest point outside of the Himalayas and Karakorams. If you're looking at a physical map, this area is a dark, dark brown, indicating extreme elevation.

As you move west into Afghanistan, the mountains start to fan out. They lose some of their height but gain a lot of complexity. They turn into these finger-like ridges that reach toward Bamiyan and Herat. By the time the range approaches the Iranian border, it’s mostly just high, dusty plateaus and weathered hills.

The Border Paradox

It’s weird because the Hindu Kush doesn't really follow political lines. It defines them. The Durand Line, which is the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, cuts right through these peaks. This has caused a massive headache for mapmakers and governments for over a century. If you look at a political map, the border looks like a jagged line drawn by someone with a shaky hand. That’s because it follows the ridgelines and water divides.

The geography here is so vertical that "borders" are often just suggestions. People living in the valleys of Nuristan or the Wakhan Corridor have historically moved back and forth based on the seasons, not based on what a map in London or Kabul said.

The Passes That Changed History

You can’t talk about this range without talking about the passes. If the mountains are the wall, the passes are the doors. And everyone has tried to kick those doors down.

- The Khyber Pass: This is the one everyone knows. It’s the primary link between Pakistan and Afghanistan. For thousands of years, if you wanted to trade silk or conquer an empire, you went through Khyber.

- The Salang Pass: This is the modern lifeline. It features a tunnel—the Salang Tunnel—built by the Soviets in the 1960s. It sits at about 11,200 feet. It is terrifying. It’s narrow, dark, and often choked with exhaust fumes, but it’s the only way to get heavy trucks from Kabul to the northern provinces.

- The Unai Pass: Further west, this pass connects Kabul to the central highlands of the Hazara people.

Alexander the Great did it. Genghis Khan did it. The Mughals did it. They all had to navigate these narrow gaps. When you look at the Hindu Kush mountains on map, you see how the Silk Road was forced to bend and twist around these granite obstacles. It wasn't a straight line; it was a desperate scramble through the easiest gaps.

Why the Geography is So Hostile

It’s a rain shadow desert. That sounds like a contradiction, but it’s the reality. The mountains are so high they block the monsoon rains coming from the Indian Ocean. This means the southern slopes might get some greenery, but the northern faces are often barren, lunar landscapes.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With the Egypt Shark Attack Russian Incident

The rock is mostly metamorphic—schist and gneiss—interspersed with granite. It’s crumbly. Landslides are a daily occurrence. In 2015, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake struck the Hindu Kush, and because the mountains are so steep and the soil is so unstable, the secondary damage from falling rocks was almost as bad as the shaking itself.

There’s also the "Hidden Water" issue. Most of the water in this region doesn't come from rain; it comes from snowmelt. If the glaciers in the eastern Hindu Kush disappear due to climate change—and they are melting—the millions of people downstream in the Indus and Amu Darya basins are in serious trouble. The map of the future might look a lot browner than the map of today.

Nuristan and the "Kafirs"

One of the most fascinating spots on the map is Nuristan. Historically called Kafiristan (Land of the Infidels), this area remained isolated for centuries. The mountains here are so incredibly difficult to traverse that the people kept their ancient polytheistic traditions long after the rest of the region converted to Islam.

It wasn't until the late 1890s that Emir Abdur Rahman Khan conquered the area and renamed it Nuristan (Land of Light). Even today, if you look at a map of roads in Afghanistan, Nuristan is basically a blank spot. There are very few paved ways in or out. It’s a geographical fortress.

Mapping the Modern Conflict

Geopolitics is just geography with guns. The Hindu Kush mountains on map explain why the last forty years of conflict in Afghanistan have been so "stalemated."

Guerrilla fighters love these mountains. The caves of Tora Bora or the Panjshir Valley are natural bunkers. The Panjshir, specifically, is a narrow valley surrounded by 14,000-foot peaks. It’s almost impossible to invade with a traditional army. The Soviets couldn't take it in the 80s, and it remained a pocket of resistance for decades.

If you’re a military planner looking at this terrain, you’re looking at a nightmare. Supply lines have to travel through narrow "choke points" where a single fallen boulder or a well-placed IED can stop a whole convoy.

Remote Sensing and New Maps

In 2026, we don't just use paper maps. We use LiDAR and high-res satellite imagery. Organizations like the USGS (United States Geological Survey) have mapped the mineral wealth of the Hindu Kush extensively. Underneath those forbidding peaks lies a fortune in lithium, copper, and rare earth elements.

But here is the catch: knowing where the minerals are on a map is one thing; getting them out of a 15,000-foot valley with no roads is another. The geography that protected the local tribes for centuries is now the primary barrier to the country's economic development.

A Note for Travelers and Researchers

If you are actually planning to go or are just doing deep research, don't trust a standard road map.

Google Maps is great, but it often underestimates travel times in the Hindu Kush by about 400%. A distance that looks like a two-hour drive on your screen can easily take twelve hours in reality. You have to account for "switchbacks"—those zig-zagging roads that climb thousands of feet in just a few miles.

Also, look at the seasonality. Many of the higher passes, like the Khawak Pass, are closed by snow from November until May. On a digital map, the road looks "open," but in the real world, it’s under ten feet of drift.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights

If you’re studying the Hindu Kush or looking to understand the region’s layout, keep these practical steps in mind:

- Use Topographic Layers: When viewing the Hindu Kush mountains on map, always toggle the "Terrain" or "Topography" view. A flat map is useless here. You need to see the contour lines to understand why cities like Kabul are located where they are (in a natural bowl surrounded by peaks).

- Check the Watersheds: To understand the local economy and survival, follow the blue lines. In the Hindu Kush, life only exists where the snowmelt flows. The Panjshir, Kunar, and Kabul rivers are the arteries of the range.

- Verify Border Points: If you are researching logistics, verify "Official Border Crossings" versus "Geographic Passes." Many passes are used by locals but aren't legal entry points for foreigners.

- Monitor Glacial Retreat: Use tools like Google Earth Engine to look at time-lapse imagery of the Hindu Kush glaciers. This is the most accurate way to see how the "Map" is physically changing as the ice disappears.

The Hindu Kush isn't just a landmark. It’s a living, shifting wall of rock that dictates how people live, how wars are fought, and how water flows in one of the most volatile parts of the world. Understanding its placement on the map is the first step to understanding the history of Asia itself.