If you open a standard atlas and try to find the great rift valley on a map, you might expect to see a single, clean line cutting through the earth like a surgical scar. It isn't that simple. Not even close.

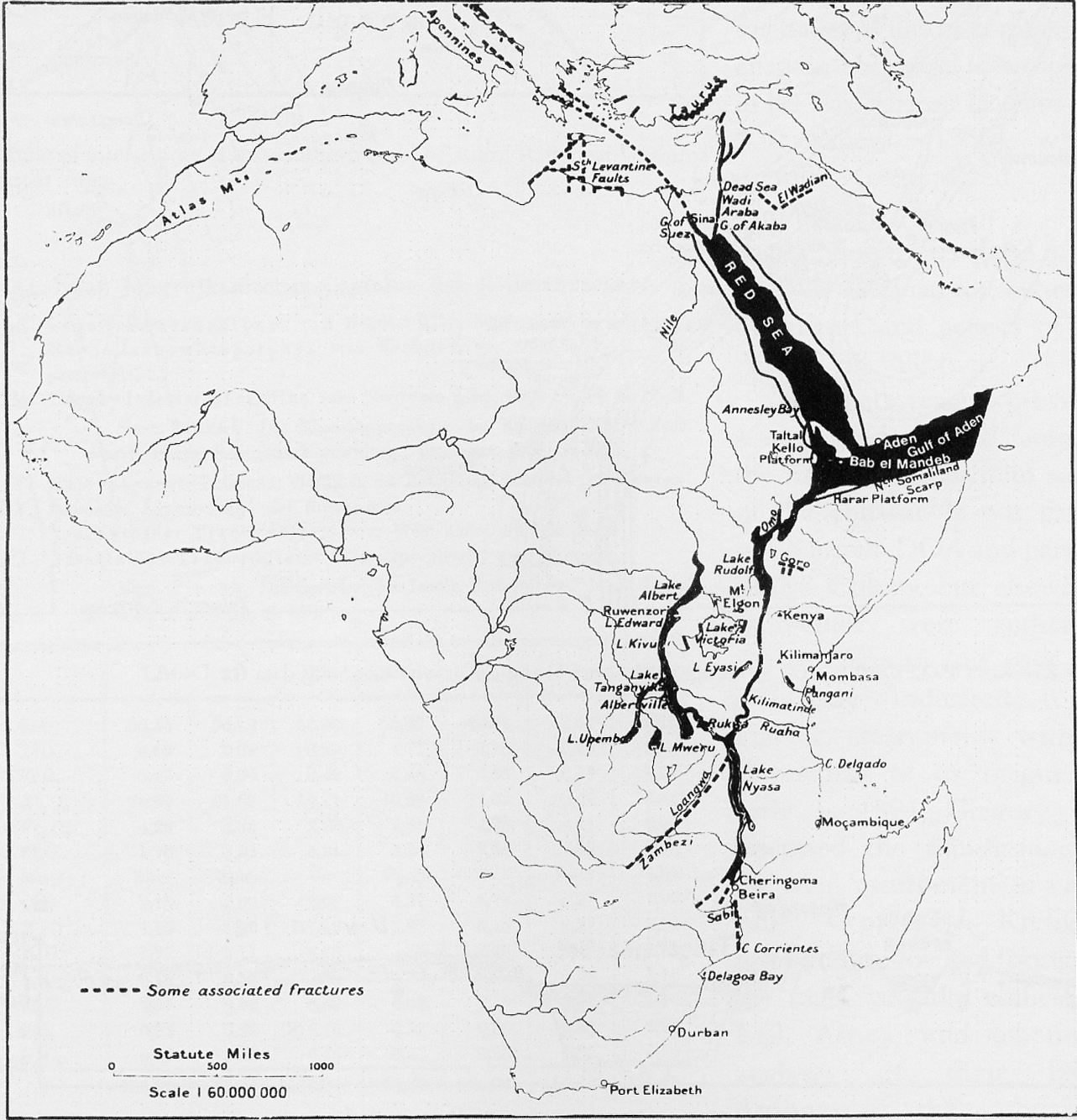

What you’re actually looking for is a 4,000-mile jagged tear in the crust that stretches from Lebanon all the way down to Mozambique. It’s huge. It’s messy. Most people think it's just a "valley" in the way we think of a mountain pass, but it’s actually a divergent plate boundary where the world is literally pulling itself apart. If you’ve ever looked at a map of Africa and wondered why the eastern side looks like it’s trying to jump ship, that’s the East African Rift system (EARS) in action.

The Visual Chaos of the Rift

Locating the great rift valley on a map requires looking for specific geological signatures. Start your eyes at the top, in the Middle East. The Dead Sea and the Jordan River Valley are actually the northernmost extensions of this system. From there, the crack plunges south through the Red Sea—which, honestly, is just a rift valley that got flooded with seawater—and hits the Afar Triple Junction in Ethiopia.

This is where things get weird.

In the Afar region, three tectonic plates—the Arabian, the Nubian, and the Somalian—are all pulling away from each other. It’s a geographer’s nightmare and a geologist’s dream. If you look at a satellite map, you’ll see the Danakil Depression. It’s one of the hottest places on Earth and sits well below sea level. It looks like another planet. Scientists like Dr. Cynthia Ebinger have spent decades documenting how the crust here is thinning so much that magma is practically bubbling at the surface.

South of Ethiopia, the rift splits into two main branches. This is the part that usually trips people up when they're staring at a map. You have the Eastern Rift (the Gregory Rift) and the Western Rift (the Albertine Rift).

👉 See also: Sumela Monastery: Why Most People Get the History Wrong

The Western Rift is famous for the "Great Lakes." Look for the long, skinny, incredibly deep lakes: Lake Tanganyika, Lake Malawi, and Lake Albert. These aren't your average round ponds. They are deep gashes filled with water. Lake Tanganyika is the second deepest lake in the world, plummeting down over 4,700 feet. On a map, these lakes form a distinct crescent shape that traces the edge of the Congo Basin.

Why Your Map Might Be Lying to You

Most maps don't label the "Great Rift Valley" as one single entity because, technically, it's a series of related rift systems. The term itself was coined by explorer John Walter Gregory in the late 19th century, but modern geology prefers the term East African Rift System.

If you're looking at a topographic map, you’ll notice the "shoulders" of the rift. These are the high-elevation areas that pushed upward as the valley floor sank. Think of the Kenyan Highlands or the Ethiopian Plateau. Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya? Those are basically the "exhaust pipes" of the rifting process. They sit right on the edges where the crust is weak enough for magma to punch through.

One thing that kinda blows people's minds is that the rift is still moving. It’s widening at about 6 to 7 millimeters per year. That sounds slow, but in a few million years, the eastern part of Africa will break off entirely, creating a new island continent and a brand new ocean. If you were to draw a map in the year 10,000,000 AD, the great rift valley on a map would be a coastline.

The Human Side of the Scars

It isn't just about rocks and plates. This geological feature is why we exist. Seriously.

✨ Don't miss: Sheraton Grand Nashville Downtown: The Honest Truth About Staying Here

The rift changed the climate of Africa. By pushing up mountains and creating deep valleys, it trapped moisture and turned lush jungles into open savannas. This environmental shift is widely believed by paleoanthropologists like the Leakey family to have forced our ancestors to stand up and walk. When you look at a map of the rift, you’re looking at the cradle of humanity. Sites like Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania are nestled right into these tectonic folds.

How to Actually Spot It on Different Map Types

- Satellite View: Look for the "string of pearls"—those long, narrow lakes in Central Africa.

- Topographic Map: Look for the dramatic drops. In places like the Mau Escarpment in Kenya, the land falls away by thousands of feet in just a few miles.

- Geological Map: Look for volcanic rock (usually shaded red or pink) concentrated along the East African corridor.

The Gregory Rift (Eastern branch) is much drier. This is where you find the soda lakes like Lake Natron and Lake Nakuru. These lakes are extremely alkaline because they have no outlet. On a high-res map, Lake Natron often looks bright red or orange because of the salt-loving microorganisms living in the burning hot water. It's beautiful and deadly.

Mapping the Future of the Continent

The rifting process is messy. In 2018, a massive crack opened up in the Suswa region of Kenya, tearing right through a highway. While some geologists argued it was just erosion, others pointed out that the underlying tectonic weakness made that erosion possible. The earth is quite literally unzipping.

We often think of continents as permanent. They aren't. They’re like pieces of a puzzle that someone is slowly pulling apart. The Great Rift Valley is the most visible "pull" happening on land today.

When you find the great rift valley on a map, don't just look for a line. Look for the volcanoes. Look for the deep-water lakes. Look for the depression where the sun beats down on salt flats. It’s a dynamic, living boundary that is constantly reshaping the geography of our planet.

🔗 Read more: Seminole Hard Rock Tampa: What Most People Get Wrong

To get the most out of your exploration, use a 3D terrain visualizer like Google Earth Pro rather than a flat paper map. Zoom into the Afar region of Ethiopia and tilt the view; you can see the crust pulling apart in real-time. Then, trace the line down through the Kenyan Rift Valley toward the Zambezi River. You’ll see how the topography dictates everything from where the cities are built to where the rain falls.

The best way to understand the scale is to look for the "V" shape formed by the two main branches encircling Lake Victoria. Lake Victoria itself isn't actually in the rift—it’s sitting on the plateau between the two cracks. It’s a shallow depression compared to the deep, rift-valley lakes on either side of it. Seeing that distinction on a map is the moment you truly "get" the geology of East Africa.

Check the seismic activity maps for the region next. You'll notice that earthquakes follow the rift lines almost perfectly, proving that the African continent is far from settled. This is active, violent, and beautiful geography.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts:

- Use Relief Maps: Standard political maps are useless for this. Use physical or relief maps to see the escarpments.

- Identify the Triple Junction: Focus on the Afar region (Ethiopia/Djibouti/Eritrea) to see where the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and East African Rift meet.

- Contrast the Lakes: Compare the shape of Lake Victoria (round, shallow) with Lake Tanganyika (long, narrow, deep) to differentiate between a structural basin and a tectonic rift.

- Track Volcanic Peaks: Follow the line of peaks from the Virunga Mountains in the west to Kilimanjaro in the east to see the "leakage" points of the rift system.

- Monitor Geological News: Follow sources like the Geological Society of London for updates on new rifting events, like the 2018 Kenya fissure.