If you look at a standard great plains on a us map, you’ll likely see a massive, nondescript beige blob stretching from Texas up to the Canadian border. It looks empty. People call it "flyover country" for a reason, right? Wrong.

That massive swath of land is actually one of the most complex, ecologically diverse, and misunderstood regions on the planet. Honestly, most people can’t even agree on where it starts or ends. Is it the 100th Meridian? Is it the Rocky Mountain rain shadow? It depends on who you ask and what kind of map they’re holding.

The Invisible Boundary: Where the Great Plains Actually Begin

Most folks think the Great Plains start exactly where the Midwest ends. It's not that simple. If you're driving west on I-70 or I-80, you won't see a sign that says "Welcome to the Plains." Instead, you’ll notice the trees start to disappear. The air gets drier. The sky suddenly feels like it’s taking up 90% of your field of vision.

Geologically, the great plains on a us map are defined by the "High Plains" and the "Low Plains." We're talking about a massive sloping plateau. It starts around 2,000 feet above sea level in the east and climbs steadily until it hits 5,000 or 6,000 feet at the base of the Rockies. This isn't just a flat floor. It’s an incline. A big one.

John Wesley Powell, the famous geologist and explorer, pointed to the 100th meridian west as the "line of aridity." This is the invisible wall where the lush, rain-fed East stops and the dry, windy West begins. If you look at a satellite map today, you can literally see the color change from deep green to dusty brown along this line. It’s the most significant geographical divide in North America, yet we barely talk about it.

Why the Map Scales are Deceiving

Maps are liars. When you see the great plains on a us map, the scale makes it look like a weekend drive. It isn't. This region covers roughly 1.1 million square miles. That’s about one-third of the entire United States. We are talking about parts of ten states: Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

The sheer scale creates a sense of "prairie madness" that early pioneers wrote about in their journals. When there are no landmarks—no mountains to aim for, no rivers to follow—the human brain struggles to process distance. You can see a storm coming from fifty miles away. You can watch the sun set for what feels like hours.

The Three Sisters of the Grassland

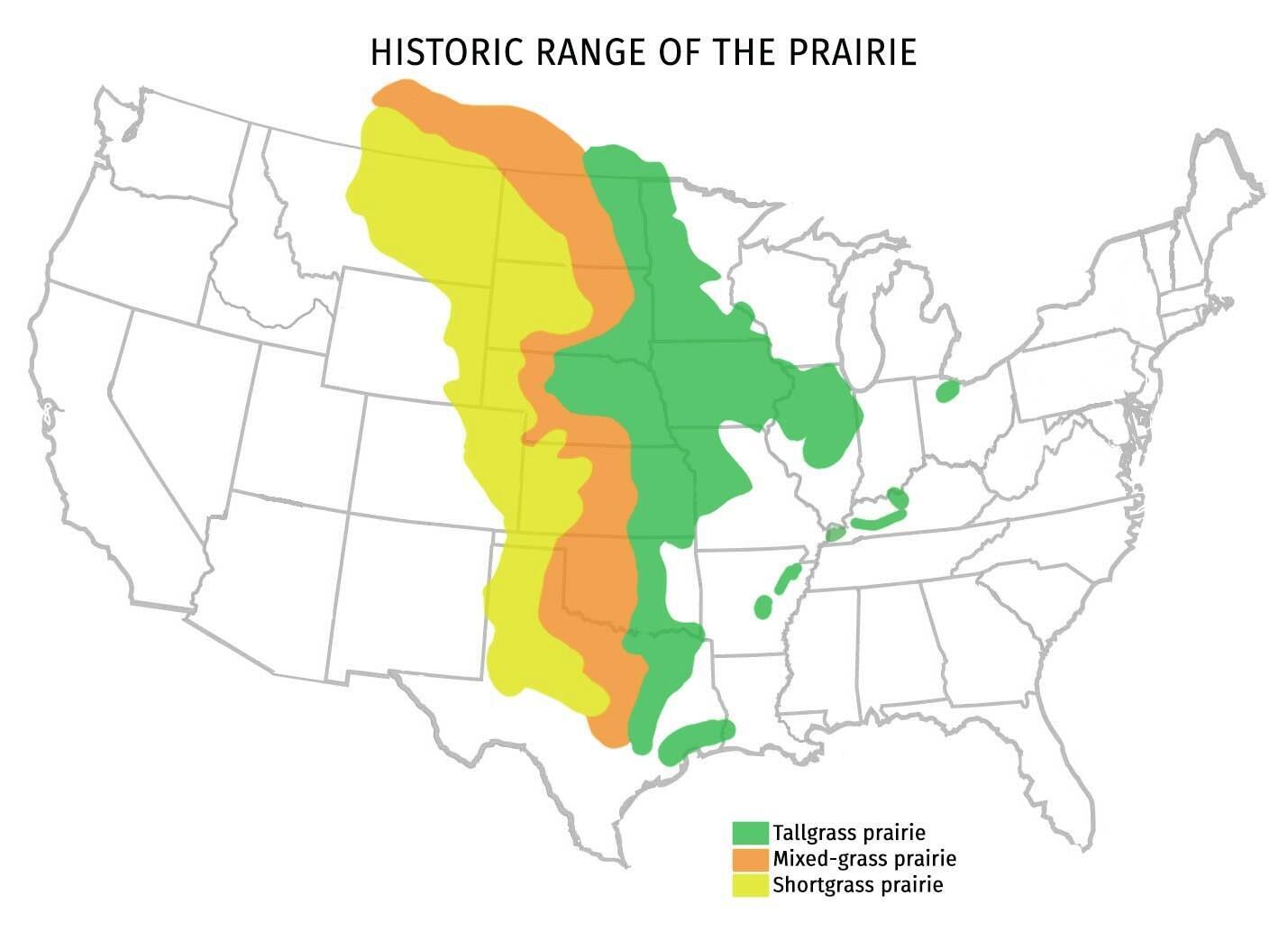

You can't talk about the Plains without talking about the grass. It's not just "grass."

- Tallgrass Prairie: This is the eastern edge. Think Iowa and eastern Kansas. Before the steel plow, this grass grew eight feet tall. You could lose a horse in it. Today, less than 4% of the original tallgrass remains.

- Mixed-grass Prairie: The middle child. It’s the transition zone where the rain starts to fail.

- Shortgrass Prairie: This is the High Plains. Buffalograss and blue grama. These plants are tough. They can survive droughts that would kill a cactus.

The Great American Desert Misconception

Back in the 1820s, Stephen H. Long called this area the "Great American Desert." He thought it was useless for farming. Then, in the late 1800s, we had a few wet years and everyone decided he was an idiot. "Rain follows the plow," they said. They were catastrophically wrong.

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a direct result of trying to treat the Great Plains like the humid East. We ripped up the deep-rooted sod and replaced it with shallow-rooted wheat. When the inevitable drought hit, the soil just... left. It blew all the way to Washington D.C.

Even today, we are struggling with the Ogallala Aquifer. This is a massive underground "fossil water" lake that sits beneath the great plains on a us map. We are pumping it out for industrial corn and beef production much faster than the rain can refill it. In parts of Kansas and the Texas Panhandle, the water table is dropping by feet every year. When that water runs out, the map is going to change again.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Surprising Spots You Didn't Know Were There

If you think it's all flat wheat fields, you haven't looked closely enough at the topography.

- The Black Hills: Rising out of South Dakota like a dark island, these mountains are actually part of the Plains province. They are older than the Rockies and hold some of the most sacred sites for the Lakota people.

- The Sandhills of Nebraska: This is the largest sand dune formation in the Western Hemisphere. It’s stabilized by grass now, but underneath that thin layer of green is a desert waiting to happen. It’s hauntingly beautiful and incredibly quiet.

- The Palo Duro Canyon: Tucked away in the Texas Panhandle, this is the second-largest canyon in the United States. You're driving along a flat road and suddenly the earth just opens up into red rock towers and deep ravines.

The Human Element: Small Towns and Ghost Frontiers

The great plains on a us map are littered with what sociologists call "frontier counties." These are places with fewer than six people per square mile. In much of the Dakotas and eastern Montana, the population is lower now than it was in 1920.

There is a strange, quiet beauty in the abandonment. You see 19th-century schoolhouses standing alone in a sea of grass. You see towns where the only thing left is a grain elevator and a post office. But there’s also a massive resurgence in Indigenous land management. Tribes like the InterTribal Buffalo Council are bringing bison back to the landscape. Bison are the "engine" of the Plains; their grazing habits actually help the grass grow better and sequester more carbon in the soil.

Understanding the Climate Extremes

This is the most volatile weather region in the world. Period. Because there are no mountain ranges running east-to-west to block air flow, cold arctic air from Canada slams into warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico.

The result? Tornado Alley.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

But it’s not just the twisters. It’s the "Derecho" wind storms that can flatten a town in minutes. It’s the blizzards that can drop the temperature 50 degrees in an hour. Living on the Great Plains requires a certain kind of psychological grit. You have to be okay with the fact that nature is much bigger than you are.

How to Actually Experience the Plains

If you want to see the real great plains on a us map, don't just stick to the Interstates. I-80 is designed to be boring so trucks can move fast.

Instead, take Highway 83. It runs north-to-south from Canada down to Mexico, cutting straight through the heart of the High Plains. You’ll see the terrain shift from the glaciated potholes of North Dakota to the massive cattle ranches of Nebraska and the rugged mesas of the Oklahoma Panhandle.

Stop in a town like Valentine, Nebraska, or Canadian, Texas. Talk to the people at the local diner. You'll find a culture that is deeply tied to the land, fiercely independent, and surprisingly hospitable. They know something most of the country has forgotten: how to live in a place where the horizon never ends.

Essential Takeaways for Your Next Trip

- Check the Wind: Seriously. Wind speeds on the Plains average 10–15 mph higher than the rest of the country. If you’re towing a trailer, be careful.

- Download Maps Offline: Cell service is a suggestion, not a guarantee. Once you get off the main drag, you are on your own.

- Look for the "Washboard": The High Plains are often "dissected," meaning they are cut by thousands of tiny draws and creek beds that aren't visible until you're right on top of them.

- Respect the Bison: If you visit a place like Theodore Roosevelt National Park, remember that bison are essentially 2,000-pound motorcycles with horns. They are faster than you.

The Great Plains aren't a space to be hurried through. They are a destination in themselves. When you look at that great plains on a us map, don't see a void. See an ocean of grass that shaped the American identity, a place where the sky is the only ceiling, and where the history of the continent is written in the wind and the soil.

Practical Next Steps for Your Journey:

- Map Out a "Blue Highway" Route: Use a physical atlas or Google Maps to find North-South highways like US-83 or US-281. These provide a much more authentic view of the prairie landscape than the East-West Interstates.

- Visit a National Grassland: Sites like the Oglala National Grassland in Nebraska or the Pawnee National Grassland in Colorado offer public access to untouched prairie ecosystems that look exactly like they did 200 years ago.

- Monitor the Mesonet: If you're traveling during the spring or summer, use local "Mesonet" weather stations for real-time wind and storm data, as standard weather apps often miss the localized intensity of Plains weather patterns.

- Identify the "Breaks": Look for areas on your map labeled as "breaks" (like the Missouri Breaks). These are rugged, eroded areas where the plains drop off into river valleys, offering some of the best hiking and photography opportunities in the region.