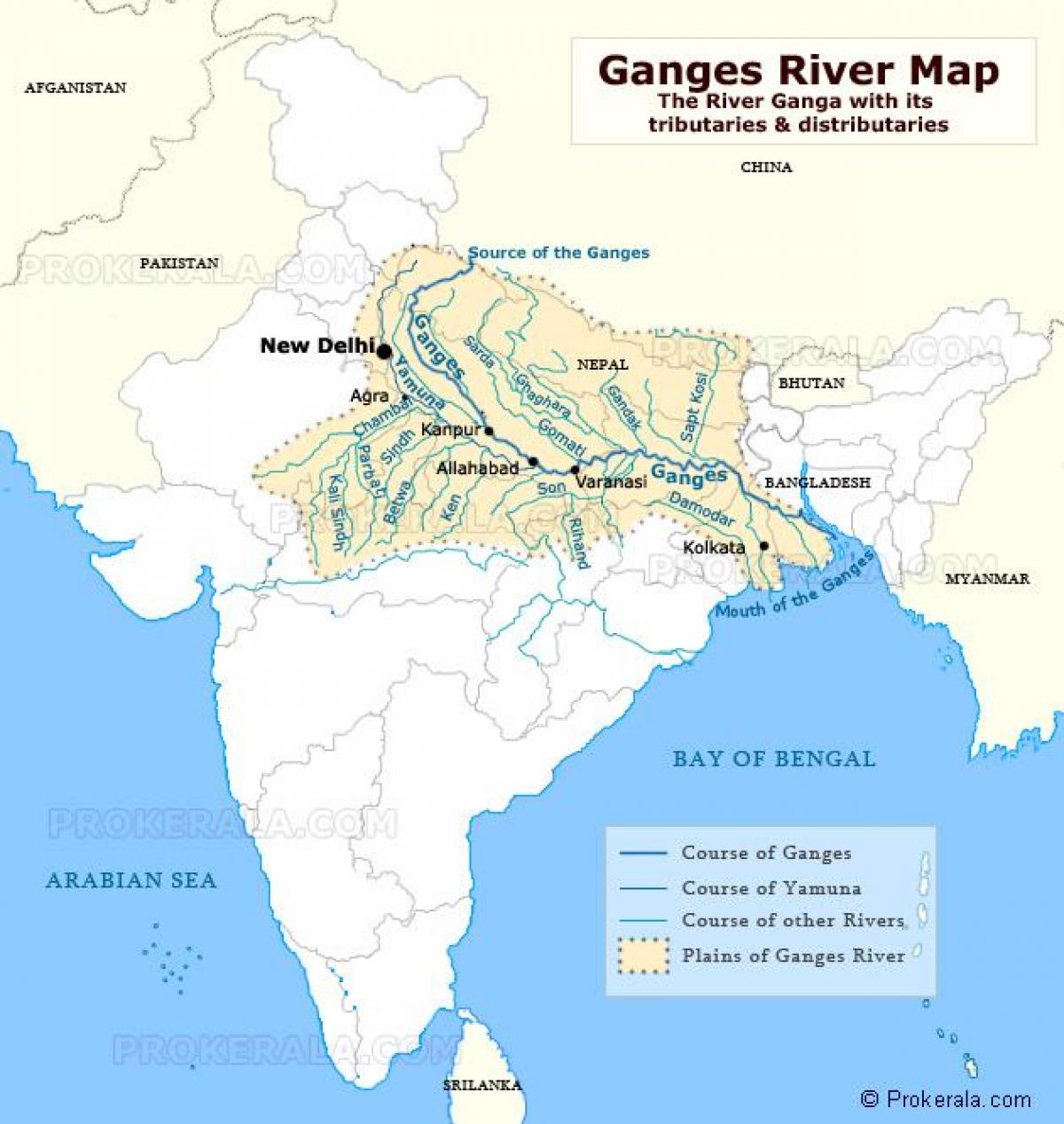

You look at a map. You see a blue line. It starts in the Himalayas, squiggles across the north, and dumps out into the Bay of Bengal. Simple, right? Honestly, looking for the Ganges in India map is usually how most people start their journey into understanding the subcontinent, but a static image never really captures the chaos, the silt, or the sheer spiritual weight of this river. It’s over 2,500 kilometers of water that basically acts as the lifeblood for half a billion people. If you’re trying to trace it, you’ve got to look past the ink.

The river doesn't just "start." It’s born from a cold, dripping ice cave called Gaumukh at the Gangotri Glacier. If you’re looking at a high-resolution topographical map, you’ll see this point tucked away in Uttarakhand at about 13,000 feet. But here’s the thing—on most maps, it isn't even called the Ganges there. It’s the Bhagirathi. It only becomes the Ganga (as locals call it) after it slams into the Alaknanda River at Devprayag. This confluence is a geographer’s dream and a pilgrim’s must-see.

The Great Arc Across the Plains

Once the river breaks out of the mountains at Rishikesh and Haridwar, the Ganges in India map takes a dramatic turn. It flattens. It slows down. It gets wide. Really wide. This is the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It’s one of the most fertile patches of dirt on the planet.

You’ve got major cities popping up like beads on a string. Kanpur, Allahabad (officially Prayagraj now), Varanasi, Patna. Each one uses the river differently. In Kanpur, it’s industrial. In Varanasi, it’s entirely transcendental. When you trace the river through Uttar Pradesh, you’ll notice it starts picking up "friends." The Yamuna is the big one. They meet at the Triveni Sangam in Prayagraj. If you’re looking at a satellite map during the Kumbh Mela, you can actually see the crowds from space. It's a literal sea of humanity where two shades of water—one greenish, one clear—struggle to mix.

✨ Don't miss: How Far Is Tennessee To California: What Most Travelers Get Wrong

Mapping the Delta: Where Things Get Messy

By the time the river hits West Bengal, the Ganges in India map becomes a bit of a nightmare for cartographers. The river splits. One branch, the Hooghly, heads south toward Kolkata. The rest flows into Bangladesh as the Padma.

Then you have the Sundarbans.

This is the world’s largest mangrove forest. It’s a literal maze. On a map, it looks like someone spilled green and blue paint and tried to comb it out. It’s a shifting landscape of tide-washed islands and man-eating tigers. Navigating this via a standard map is basically impossible because the islands disappear and reappear with the tides.

🔗 Read more: How far is New Hampshire from Boston? The real answer depends on where you're actually going

Why the Map Changes Every Year

We think of maps as permanent. They aren't. Not here. The Ganges is "braided." It moves. A village that was on the riverbank ten years ago might be two miles away today because the river decided to take a shortcut during a heavy monsoon. This is called "river migration."

In places like Bihar, the riverbed is so full of Himalayan silt that the water sits higher than the surrounding land in some spots, held back by levees. When those break, the map gets rewritten overnight.

Real Impact and Modern Mapping

If you’re using Google Earth or modern GIS (Geographic Information Systems) to look at the river, you’ll see some depressing stuff too. The pollution is visible. You can see the sediment plumes. Organizations like the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) use satellite mapping to track "nullahs" or drains that dump waste into the stream. They’ve mapped thousands of points of pollution to try and fix what’s broken.

💡 You might also like: Hotels on beach Siesta Key: What Most People Get Wrong

- Uttarakhand: The rugged, vertical start.

- Uttar Pradesh: The wide, slow middle where the big tributaries join.

- Bihar: The flood-prone stretch where the river is at its most volatile.

- West Bengal: The grand finale and the split into the delta.

Understanding the Map’s Limits

Kinda wild when you think about it—this river supports more people than the entire population of the United States. A map shows you the where, but it doesn't show you the why. It doesn't show the sound of the evening Aarti in Varanasi or the smell of the damp earth in the delta.

When you study the Ganges in India map, you’re looking at a living organism. It’s not just geography. It’s history. It’s the reason India’s civilization is where it is. If the river shifted fifty miles west tomorrow, the entire economy of the region would collapse.

Practical Next Steps for Geographic Research

If you are actually planning to visit or study these locations, don't rely on a single static map. Open up a satellite layer and look at the "oxbow lakes" near the main channel; these are old bends the river abandoned.

- Check Seasonal Changes: Look at the river's width in satellite imagery during August (Monsoon) versus April (Pre-monsoon). The difference is staggering.

- Verify Confluences: Use a GPS-enabled map to find the "Panch Prayag" in the Himalayas. These five confluences are the most accurate way to trace the river's ancestry.

- Monitor the Delta: If you're looking at the West Bengal/Bangladesh border, use a specialized maritime map. The shifting sandbars (chars) make standard road maps useless for navigation near the water.

Trace the line from Gaumukh to the Bay of Bengal, but keep in mind that the blue line is actually a pulsing, moving, and often dangerous force of nature. It’s much more than a border or a water source. It’s a 2,500-kilometer-long story that's still being written. Go beyond the basic layout and look at the topographical shifts in the Haridwar gap to see exactly how the mountains "let go" of the water into the plains. That's where the real geography begins.

---