Math shouldn't feel like a trap. Honestly, when most people look at a pyramid, they see a cool ancient tomb or maybe a fancy paperweight. But then a geometry teacher or a high-stakes engineering project asks for the formula surface area pyramid, and suddenly, the "cool" shape becomes a headache of triangles and hidden heights.

It’s just paper and space. That’s the secret.

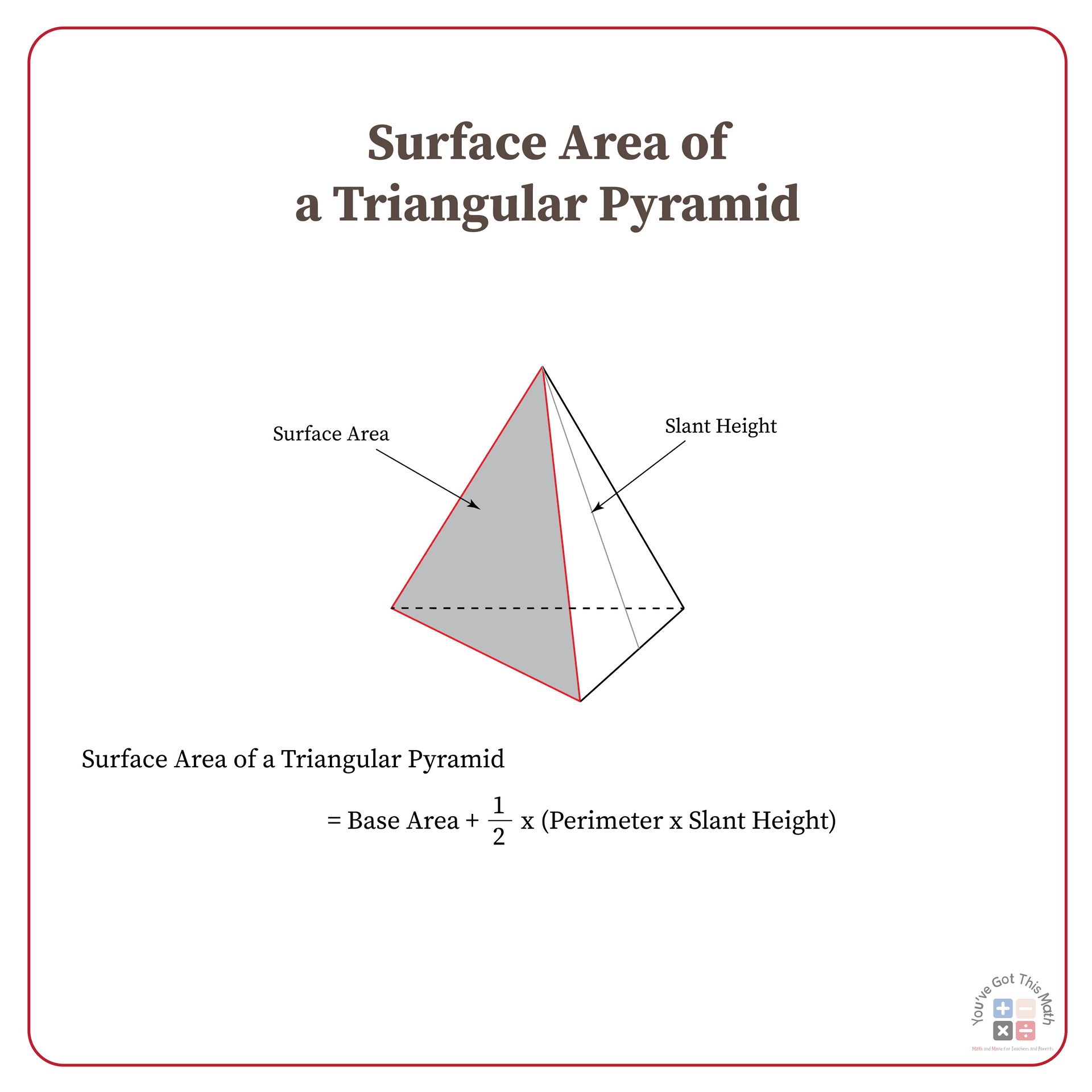

If you can unfold a cardboard box, you can master this. A pyramid isn't some mystical solid; it's a base with a bunch of triangles leaning against each other. To get the total surface area, you basically just find the area of every single flat face and add them up. It sounds tedious. It kind of is. But once you see the pattern, you’ll realize the math is actually trying to save you time.

Why the Slant Height Changes Everything

You can't just use the regular height of the pyramid. This is where everyone trips up.

There is a massive difference between the vertical height—the line that drops from the tip (the apex) straight down to the middle of the floor—and the slant height. If you were an ant crawling up the side of the Great Pyramid of Giza, you wouldn't be walking the vertical height. You’d be walking the slant. In geometry, we usually label this slant height as $l$.

Think about it this way: the triangles making up the sides are tilted. Because they are tilted, they are "longer" than the pyramid is "tall." If you use the vertical height ($h$) to calculate the area of the side triangles, your answer will be wrong every single time. Your pyramid will literally have less "skin" than it needs to cover its bones.

📖 Related: Generative AI Enterprise News Today: The Move Toward Agents and Gigawatt Factories

To find that slant height when you only have the vertical height, you usually have to pull out the Pythagorean theorem. You create a little right triangle inside the pyramid. One leg is the height ($h$), the other is half the width of the base ($s/2$), and the hypotenuse is your slant height ($l$).

$$l = \sqrt{h^2 + (s/2)^2}$$

It's an extra step. It's annoying. But without it, the formula surface area pyramid falls apart.

Breaking Down the General Formula

If you want the "one size fits all" version for a regular pyramid (where the base is a polygon with equal sides), it looks like this:

$$Surface\ Area = Base\ Area + \frac{1}{2} \times Perimeter \times Slant\ Height$$

Let's pick that apart.

The Base Area ($B$) is whatever the shape is sitting on. If it's a square, it’s $side \times side$. If it's a triangle, it's $1/2 \times base \times height$.

The second part—the $1/2 \times Perimeter \times l$—is just a shortcut. Instead of calculating four or five separate triangles and adding them together, you take the total distance around the base (the perimeter) and multiply it by the slant height, then divide by two. It’s a sleek bit of mathematical efficiency.

The Square Pyramid: The One You Actually Use

Most of the time, you're dealing with a square base. It’s the classic look. Because the base is a square, the perimeter is just $4 \times s$ (where $s$ is the side length).

When you plug that into our general formula, things get much cleaner:

🔗 Read more: How Can I Receive My Emails on My Phone: The Simple Setup Most People Miss

$$SA = s^2 + 2sl$$

Wait, where did the $1/2$ and the $4$ go? They cancelled each other out. $1/2$ of $4$ is $2$. So, you just take the area of the square ($s^2$) and add it to two times the side length times the slant height ($2sl$).

Let’s say you’re building a small wooden model. The base is 10 inches wide. The slant height is 12 inches.

The base area is $10 \times 10 = 100$.

The side area is $2 \times 10 \times 12 = 240$.

Total surface area? 340 square inches.

It’s fast. It’s logical. You don't need a PhD to see how those pieces fit together.

Rectangular Pyramids: A Different Beast

Life isn't always square. Sometimes the base is a rectangle, which means your side triangles aren't all the same. You'll have two triangles matching the "length" side and two matching the "width" side.

In this scenario, you have two different slant heights. Let's call them $l_1$ and $l_2$.

The formula stretches out:

$$SA = (L \times W) + (L \times l_1) + (W \times l_2)$$

You’re basically calculating the bottom rectangle, then the two "long" side triangles, then the two "short" side triangles. It’s more bookkeeping than complex math. If you try to use the "shortcut" perimeter formula here, you’ll get a result that doesn't account for the different slopes. Accuracy matters, especially if you're ordering expensive materials like glass or sheet metal.

Real-World Nuance: The "Open" Pyramid

Here is something textbooks often skip: sometimes you don't need the base.

Think about a glass roof or a tent. The "surface area" usually refers only to the Lateral Area. If you're calculating how much fabric you need for a pyramid tent, you aren't going to buy fabric for the floor—usually, that's a separate tarp or just grass.

In that case, you drop the "Base Area" part of the equation entirely.

$$Lateral\ Area = \frac{1}{2} \times P \times l$$

Experts in architecture, like those who worked on the Louvre Pyramid in Paris, have to account for these distinctions. They also have to think about the thickness of the material. A formula gives you the area of a mathematical plane with zero thickness. In the real world, glass has edges. Metal frames have width.

If you are working on a DIY project, always buy about 10% more material than the formula suggests. Cuts go wrong. Measurements waver. Math is perfect; humans aren't.

The Triangular Pyramid (The Tetrahedron)

These are the weird ones. A triangular pyramid has a triangle for a base. If all the faces are equilateral triangles, it’s called a regular tetrahedron.

The math here looks intimidating because of all the square roots involved in triangle areas, but for a regular tetrahedron with side length $a$, the formula simplifies down to:

$$SA = \sqrt{3} \times a^2$$

That is an incredibly elegant way to describe a complex 3D shape. It’s one of those moments where geometry feels less like a chore and more like a language.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

I’ve seen people try to find the formula surface area pyramid by using the volume formula by mistake. Don't be that person. Volume measures how much water you can pour inside; surface area measures how much paint you need to cover the outside.

Another big mistake? Mixing units.

If your base is measured in centimeters but your height is in inches, your final number is gibberish. Convert everything to a single unit before you even touch a calculator.

Also, watch out for "irregular" pyramids. If the apex isn't directly over the center of the base, the slant height will be different for every single face. At that point, the "shortcuts" are dead. You have to calculate each triangle individually using its own specific base and slant height. It’s tedious, but it’s the only way to stay factually accurate.

✨ Don't miss: Why the ChatGPT Enslaving Humanity Meme Still Makes Us Nervous

Actionable Steps for Your Calculations

Ready to actually solve something? Follow this workflow to avoid mistakes:

- Identify the base shape. Is it a square, rectangle, or triangle? Write down the formula for its area immediately.

- Find the Slant Height ($l$). Check if the problem gave you the vertical height ($h$) or the slant height ($l$). If it's $h$, use the Pythagorean theorem to find $l$.

- Calculate the Perimeter. Add up all the sides of the base.

- Plug and Play. Use $SA = Base\ Area + (0.5 \times Perimeter \times l)$.

- Sanity Check. Does the number feel right? If your base is 100 square feet, your total area shouldn't be 105—the sides are almost always significantly larger than the base.

If you’re doing this for a school assignment, draw the "net"—the unfolded version of the pyramid. Seeing the five shapes (for a square pyramid) laid out flat makes it nearly impossible to forget a side.

For those using this for 3D printing or construction, remember to account for "overlap" or "seam allowance." The math tells you the exact surface, but you need a little extra to actually glue or weld the pieces together.

Geometry isn't about memorizing strings of letters. It's about seeing the components. Once you see the triangles, the formula isn't a rule anymore—it's just a description of what's already there.