Chemistry isn't just about explosions and bubbling beakers. Honestly, most of it is just fancy accounting. You’re tracking atoms like a CPA tracks pennies. When you're trying to figure out how to find the empirical formula of a compound, you're basically looking for the simplest, most stripped-down ratio of elements in a substance. Think of it like a recipe. If a cake recipe calls for 4 eggs and 2 cups of flour, the "empirical" version is just 2 eggs for every 1 cup of flour. It’s the same ratio, just simplified.

People get intimidated because textbooks make it look like a nightmare of dimensional analysis. It’s not.

What is an Empirical Formula, Anyway?

Before we dive into the math, let’s get one thing straight. The empirical formula is the lowest whole-number ratio of atoms in a compound. This is different from a molecular formula. Take glucose, for instance. Its molecular formula is $C_6H_{12}O_6$ because that is exactly what’s in one molecule. But if you divide everything by 6, you get $CH_2O$. That’s the empirical formula. It tells you the relationship between the atoms, but not necessarily the total count. Some things, like water ($H_2O$) or salt ($NaCl$), have the same empirical and molecular formulas because you can’t simplify them any further. You can't have half an atom.

The "Percent to Mass" Mental Trick

Usually, you start with percentages. A lab technician might tell you a sample is 40% carbon, 6.7% hydrogen, and 53.3% oxygen. This is where people trip up. They see percentages and panic. Don't. Just assume you have 100 grams of the stuff. Seriously. If you have 100g, then 40% becomes 40g. 6.7% becomes 6.7g. It’s a magic trick that makes the math actually doable.

Once you have grams, you’re halfway there. But grams are useless for ratios because different atoms have different weights. A gram of lead is a tiny speck; a gram of hydrogen is a giant balloon. To compare them fairly, we need moles.

🔗 Read more: How to Unlock Samsung Mobile Phones When You're Actually Stuck

Step 1: Mass to Moles

This is where your periodic table comes in. You need the atomic mass of each element. For our example:

- Carbon (C): 12.01 g/mol

- Hydrogen (H): 1.008 g/mol

- Oxygen (O): 16.00 g/mol

You divide your mass by these numbers. For Carbon, it's $40 / 12.01$, which is about 3.33 moles. Hydrogen gives you $6.7 / 1.008$, roughly 6.65 moles. Oxygen is $53.3 / 16.00$, which is 3.33 moles. Now you have a ratio, but it’s a messy, decimal-filled ratio. Nobody wants to write a formula like $C_{3.33}H_{6.65}O_{3.33}$. That looks insane.

Why the "Divide by Smallest" Rule Works

To fix those ugly decimals, you find the smallest number in your mole list. In our case, it's 3.33. You divide every single mole value by that number.

$3.33 / 3.33 = 1$ (for Carbon)

$6.65 / 3.33 = 2$ (for Hydrogen)

$3.33 / 3.33 = 1$ (for Oxygen)

Boom. $CH_2O$. You just found the empirical formula. It feels like a relief when the numbers come out clean, doesn't it? But honestly, they don't always come out clean. Nature is messy.

When the Math Goes Sideways: Handling Decimals

Sometimes you do all that work and end up with something like 1.5. You can't just round 1.5 to 2. That’s a huge error in chemistry. If you have a .5, you multiply everything in the ratio by 2 to get a whole number. If you have a .33, you multiply by 3. If you have a .25, you multiply by 4.

Imagine you’re working with an iron oxide sample. You do the math and get 1 mole of Iron for every 1.5 moles of Oxygen. Multiply both by 2. Now you have 2 moles of Iron and 3 moles of Oxygen. The formula is $Fe_2O_3$. That’s rust. If you had rounded 1.5 down to 1, you’d have $FeO$, which is a completely different substance used in glazes and glass. Details matter.

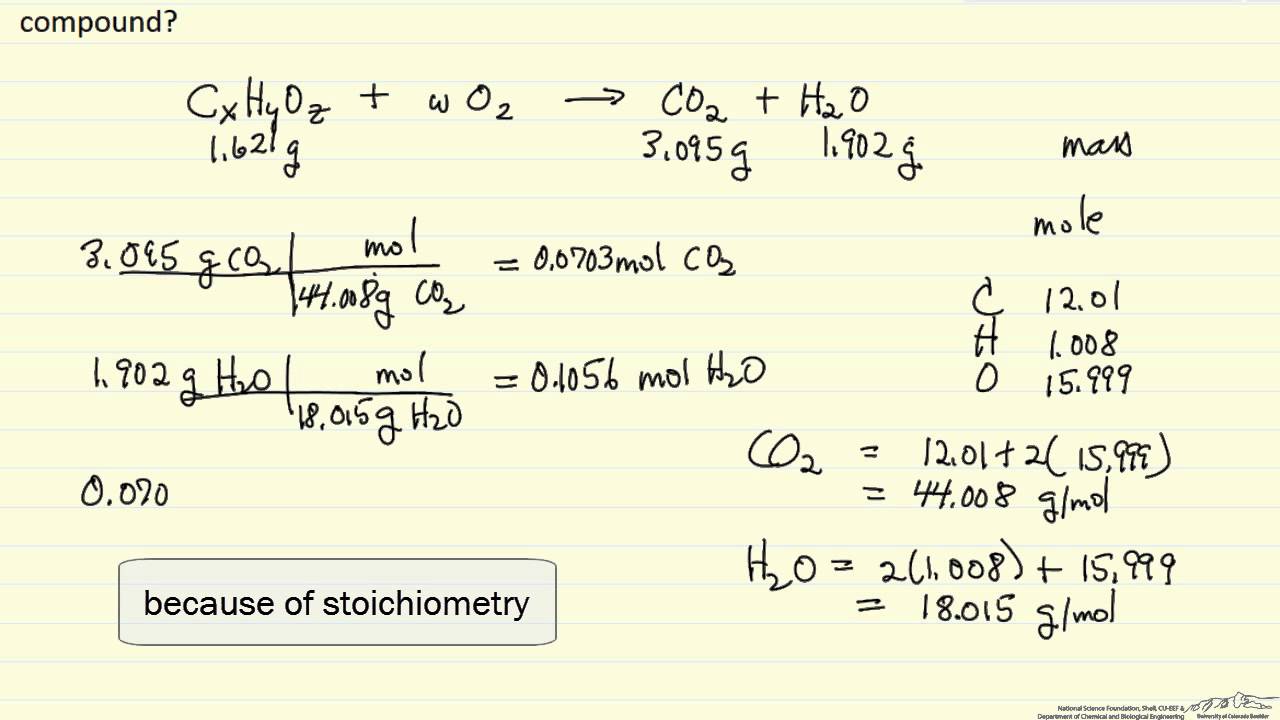

Real-World Nuance: Combustion Analysis

In actual research labs—places like the Mayo Clinic or specialized materials labs—scientists don’t just get handed percentages. They use combustion analysis. They burn a sample and measure the $CO_2$ and $H_2O$ produced.

It’s a bit of a puzzle. All the carbon in the $CO_2$ came from the original sample. All the hydrogen in the $H_2O$ came from the original sample. You calculate the mass of Carbon and Hydrogen from those products, subtract them from the original sample weight to find the Oxygen, and then you start the mole conversion process. It’s tedious. It’s slow. But it’s how we actually identify new drugs or pollutants in the environment.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

I’ve seen students do everything right and then fail because of a rounding error. Do not round your mole values too early. If you get 2.99, sure, that’s a 3. But if you get 2.8, you better check if you need to multiply by a factor or if you made a calculation error earlier.

Another big one? Mixing up the atomic mass (the number on the bottom of the square in the periodic table) with the atomic number (the one on top). If you use the atomic number, your ratio will be pure fiction.

Quick Reference for Multipliers:

- Ends in .20: Multiply everything by 5

- Ends in .25: Multiply everything by 4

- Ends in .33: Multiply everything by 3

- Ends in .50: Multiply everything by 2

- Ends in .66: Multiply everything by 3

Moving from Empirical to Molecular

Once you've nailed how to find the empirical formula of a compound, the next logical step is finding the "real" molecular formula. You need the molar mass of the actual compound for this.

Let’s say our $CH_2O$ example has a known molar mass of 180 g/mol.

First, calculate the mass of the empirical formula: $12 + (2 \times 1) + 16 = 30$ g/mol.

Now, divide the real mass by the empirical mass: $180 / 30 = 6$.

This means the real molecule is 6 times bigger than the empirical one. Multiply every subscript by 6: $C_6H_{12}O_6$.

Practical Insights for Success

If you're doing this for a test or a lab report, write out your units. Every single time. Writing "g C" or "mol H" keeps you from getting lost in the numbers. Chemistry is less about being a math genius and more about being organized.

- Get a reliable periodic table. Don't guess the masses.

- Use at least four significant figures. Rounding to "12" instead of "12.01" for Carbon can actually change your final ratio if the sample is large.

- Check your work backward. If you think the formula is $C_2H_6O$, calculate the mass percentages of that formula and see if they match your starting data.

To truly master this, grab a practice problem involving a hydrate—compounds that have water molecules trapped inside them. The process is the same, but you treat the $H_2O$ unit as its own "element" when calculating the ratio. Once you can solve a hydrate problem, you’ve basically conquered the topic.