If you pull up a high-resolution version of the Congo River on map, your first instinct is probably to look for the "C" shape. It’s a giant, sweeping arc that cuts through the heart of Africa, crossing the equator not once, but twice. Most people think of rivers as straight lines from A to B. The Congo? It's basically a giant, liquid question mark. It starts in the highlands of Zambia, flows north into the sweltering jungle, hooks left, and then dives south toward the Atlantic. It's weird. It's massive. And honestly, it's one of the most misunderstood geographical features on the planet.

Most maps don't do it justice. They show a blue thread, but they miss the fact that this river is the deepest on Earth. We’re talking over 700 feet down in some spots. That’s deep enough to hide the Space Needle with room to spare.

Where the Congo River on Map Actually Begins

Finding the source is a bit of a headache. If you’re looking at a standard political map, you might see the Lualaba River. That’s the main "stem." But geographers like to argue. Some say the true source is the Chambeshi River in Zambia. If you trace the Congo River on map from the very tip of its longest tributary, you're looking at a 2,920-mile journey. It’s the second-longest in Africa, trailing only the Nile, but in terms of sheer power, the Nile is a garden hose compared to the Congo's fire hydrant.

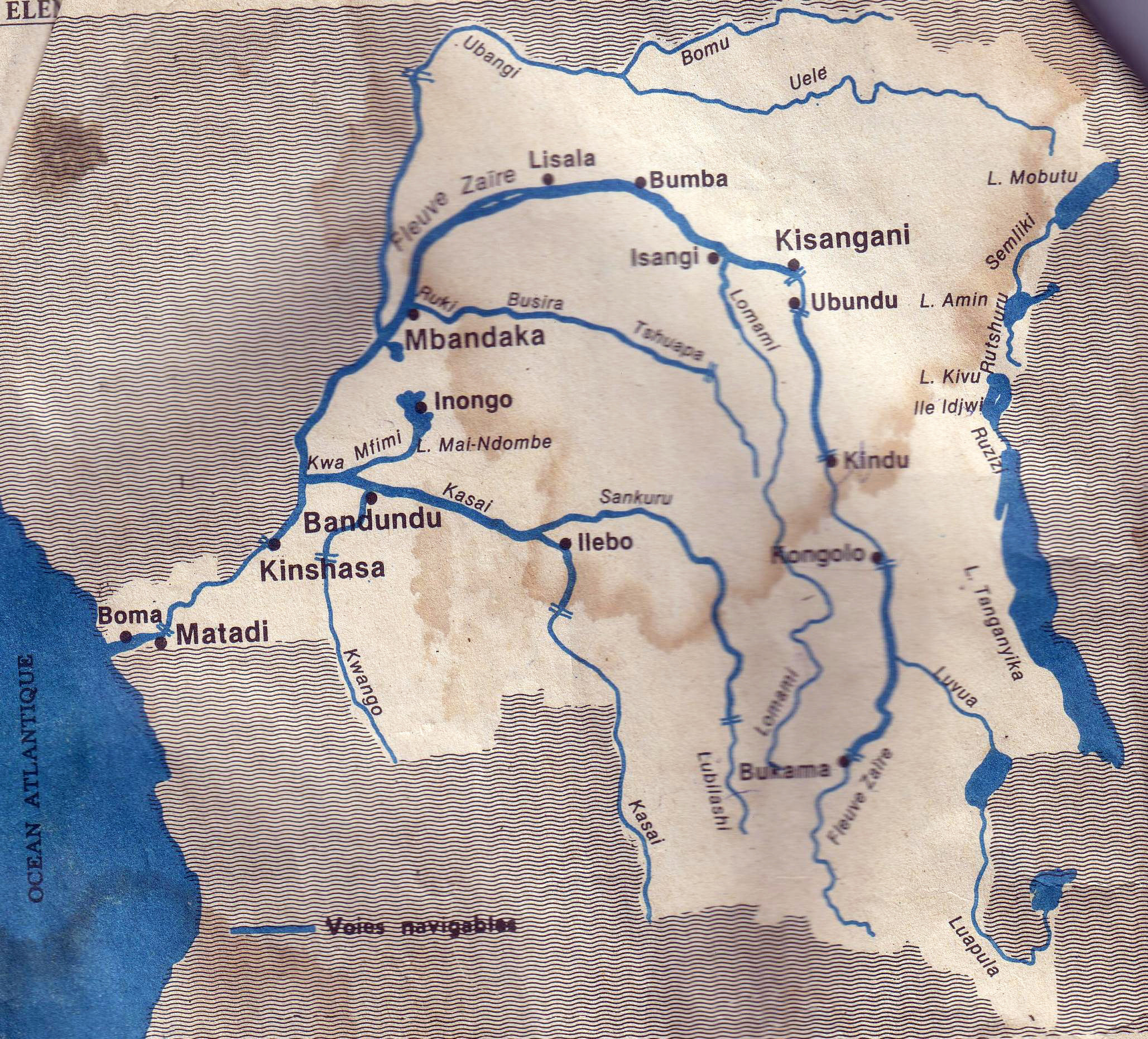

The river basin covers about 1.3 million square miles. That’s basically the entire size of India tucked into the middle of the African continent. When you look at the map, you’ll see it touches almost every country in Central Africa—the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, western Zambia, northern Angola, and parts of Cameroon and Tanzania. It’s the highway of the continent. There are hardly any paved roads in the deep interior of the DRC, so if you want to move charcoal, fish, or people, you're getting on a boat.

The Famous Horseshoe Bend

Look at the top of the arc on a map. You’ll see a spot where the river reaches its northernmost point before swinging back south. This is the "Cuvette Centrale." It’s a massive, shallow depression filled with swamp forest. On a satellite map, this area looks like a solid wall of deep broccoli-green. It’s one of the most carbon-rich places on Earth. Scientists from the University of Leeds recently mapped the peatlands here, finding that they store about 30 billion tons of carbon. That’s equivalent to three years of global fossil fuel emissions.

💡 You might also like: Weather in Lexington Park: What Most People Get Wrong

Navigating the Living Map: Why You Can’t Just Sail Across

You’ve probably seen movies where people cruise smoothly down tropical rivers. The Congo isn't like that. If you look at the Congo River on map between Kinshasa and the Atlantic Ocean, you'll notice a short, jagged stretch. This is where the river drops about 900 feet in just 200 miles.

It's called the Livingstone Falls.

It’s not one big waterfall like Niagara. It’s a series of brutal rapids that make the river completely unnavigable for ocean-going ships. This is why the twin capitals, Kinshasa and Brazzaville, sit right where they do. They are located at Malebo Pool, a wide, lake-like expansion of the river just above the rapids. Beyond this point, the river is a 1,000-mile liquid highway into the interior. Below it? It’s a death trap of churning white water.

The Deepest Water on Earth

Near the mouth of the river, in a stretch called the Lower Congo, the water gets terrifyingly deep. This isn't just a fun fact; it actually changes how evolution works. Because the current is so strong and the water so deep, fish populations on one side of the river can't cross to the other. They are effectively separated by a wall of water. Over thousands of years, they’ve evolved into different species. You can find "blind" fish here that have evolved to live in the lightless depths, specifically the Lamprologus lethops. It’s the only place on a map where a river acts like an ocean or a mountain range, physically barring land animals and fish from crossing.

📖 Related: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

The Human Impact Along the Blue Line

Maps often skip the people. But you can't understand the Congo without the 75 million people who live in its basin. The river is the lifeblood for cities like Kisangani, Mbandaka, and the mega-metropolis of Kinshasa.

- Economic Transit: Barges the size of football fields lashed together, carrying thousands of people and tons of goods.

- Hydroelectric Potential: There is a spot on the map called Inga Falls. Engineers have been obsessed with it for decades. They believe if we built the "Grand Inga" dam, it could power nearly half of the African continent.

- Conflict and History: The river was the primary route for King Leopold II’s agents during the horrific rubber trade of the late 19th century. The map of the Congo is, unfortunately, also a map of colonial extraction.

The river is also a divide. Between Kinshasa (DRC) and Brazzaville (Republic of the Congo), the river is about 2 to 6 miles wide. These are the two closest capital cities in the world, yet there is no bridge connecting them. You have to take a ferry. It sounds crazy, but the sheer volume of water moving at 1.5 million cubic feet per second makes building a bridge an engineering and political nightmare.

Identifying the Key Landmarks on Your Map

When you are scanning the Congo River on map, keep an eye out for these specific markers to get your bearings:

- Boyoma Falls (Stanley Falls): Located near Kisangani. This marks the end of the Lualaba and the official start of the "Congo" river. It consists of seven cataracts.

- The Ubangi River: This is the largest right-bank tributary. It forms the border between the DRC and the Central African Republic.

- The Kasai River: The largest left-bank tributary. It brings in water from the south and is a major transport route for the diamond-rich regions.

- Malebo Pool: Formerly Stanley Pool. It’s about 22 miles long and 14 miles wide. This is where the river slows down before the chaos of the lower rapids.

Surprising Realities of the Congo Basin

Most people think the Amazon is the only "green lung" of the world. Kinda true, but the Congo is catching up in importance. While the Amazon is being deforested at an alarming rate, the Congo Basin remains relatively intact, mostly because it's so difficult to access. There aren't many roads on the Congo River on map because the ground is basically a sponge.

👉 See also: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

The river also creates its own weather. The evaporation from the massive canopy and the river itself feeds the tropical storms that eventually cross the Atlantic. Some researchers suggest that the health of the Congo River directly impacts the intensity of hurricane seasons in the Caribbean and the United States. It's all connected.

Practical Steps for Geographic Research

If you’re trying to use a map of the Congo for a project, travel planning, or just satisfy a late-night curiosity, keep these tips in mind:

- Use Topographic Layers: A flat map won't tell you why the river stops being navigable. You need to see the elevation drop at the Crystal Mountains near the coast.

- Check Seasonal Changes: The Congo crosses the equator. This means that while the northern tributaries are in a dry season, the southern ones are in a wet season. The river's flow is actually more stable than the Nile because someone, somewhere, is always getting rained on.

- Satellite vs. Vector: Use Google Earth or Sentinel-2 imagery to see the "sediment plume." The Congo pushes so much mud into the Atlantic that you can see a brown stain in the blue ocean for up to 200 miles off the coast.

Understanding the Congo River isn't just about tracing a line. It’s about recognizing a massive, high-pressure engine that drives the climate, the economy, and the survival of Central Africa. Next time you look at that big blue arc, remember you’re looking at a canyon drowned in freshwater, a wall that creates species, and a road that never needs paving.

To get a better sense of the scale, compare the Congo’s width at Mbandaka to the width of the Mississippi at New Orleans on the same map scale. You'll quickly see that the Congo is a completely different beast, often stretching so wide that you can't see the other bank through the tropical haze.