If you open up Google Maps or Baidu Maps right now and type in "Great Wall," you’re going to be disappointed. Seriously. You’ll probably see a tiny red pin dropped on a random stone gate near Beijing called Badaling. But that’s like trying to find the entire Atlantic Ocean by looking at a picture of a single pier in New Jersey. Finding the actual China wall in map views requires realizing that you aren't looking for a single object. You're looking for a 13,000-mile long series of fragments, some of which are literally just piles of dirt that look like nothing from a satellite.

It's massive. It’s messy.

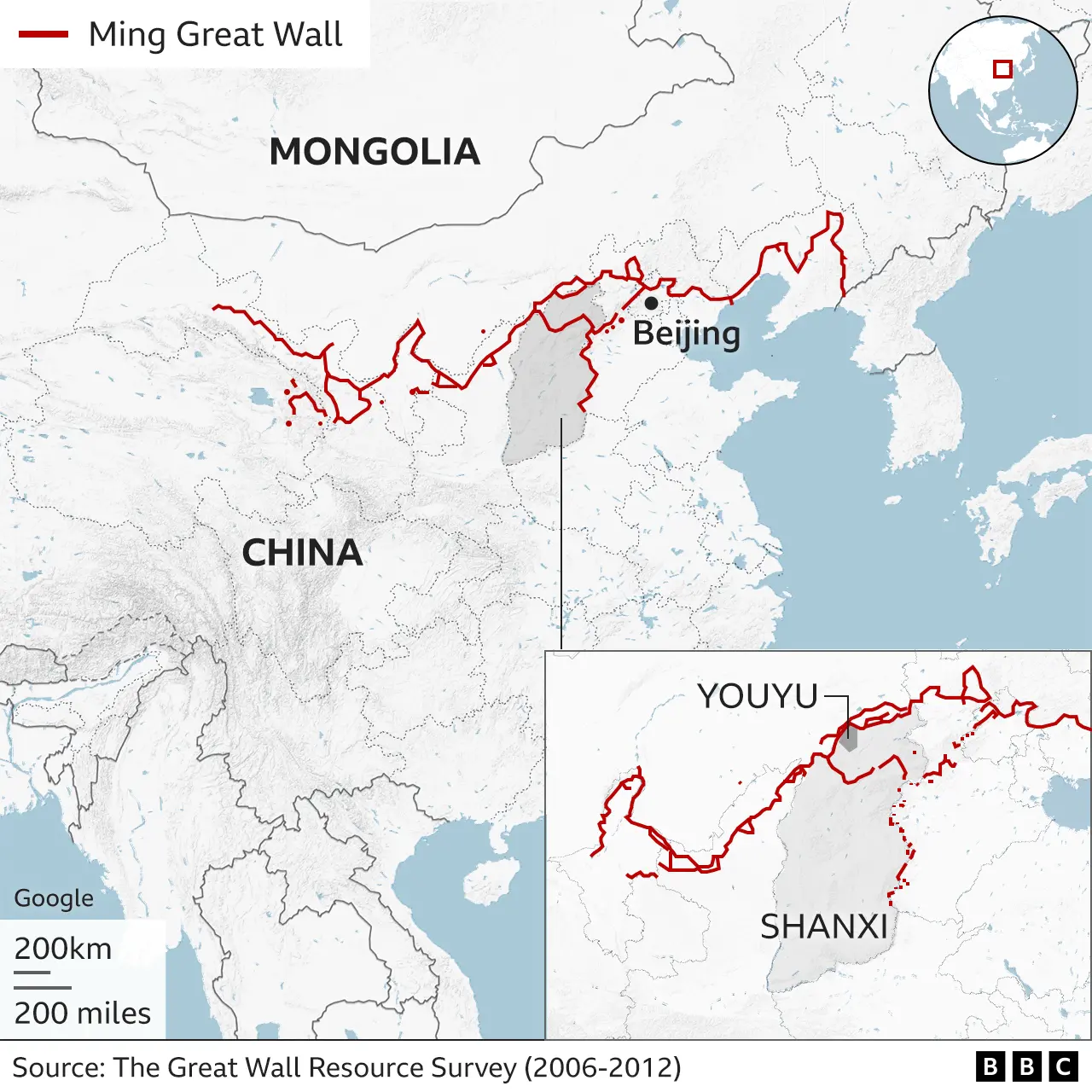

Most people think the wall is this continuous, paved stone dragon snaking across the mountains. That's the version you see on postcards. In reality, the Great Wall of China is a collection of walls, trenches, and natural barriers like hills and rivers. When you look at the China wall in map layouts, you have to understand that much of it has been swallowed by the Gobi Desert or reclaimed by farmers in the Shaanxi province.

The Mapping Headache: Why it Looks Different Online

Satellite imagery has changed how we see the world, but it struggles with the Great Wall. Why? Because the wall was built to blend in. The Ming Dynasty engineers weren't thinking about 21st-century GPS; they used local rocks and earth. In the mountains of Hebei, the wall is grey granite. In the western deserts of Gansu, it’s rammed earth—basically packed mud. On a standard map, that mud wall looks exactly like the ground around it.

If you’re looking at a China wall in map interface, you’ll notice the line "breaks" constantly. This isn't a glitch. Over the centuries, sections were stolen for building materials. During the Cultural Revolution, villagers were actually encouraged to take bricks to build pigsties and homes. So, when you're tracing the line on your screen and it suddenly vanishes into a cornfield, you're seeing the literal scars of history.

It’s actually kinda fascinating.

The Beijing "Cluster" vs. The Reality

Most tourists stick to the Beijing area. Maps make it look like the wall starts and ends there. You’ve got Badaling, which is basically the Disneyland version—totally restored, handrails everywhere, and thousands of people. Then you have Mutianyu, which is slightly better but still very much a "mapped" tourist destination.

But if you zoom out?

The wall stretches from the Yellow Sea in the east all the way to the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. To see the China wall in map data correctly, you have to look for the "First Pass Under Heaven" at Shanhaiguan where the wall meets the ocean. Then, track it westward. You'll pass through the "Wild Wall" sections like Jiankou—where the wall is so steep and broken that it’s actually dangerous to hike—and eventually reach the Jiayuguan Pass in the west.

Digital Archeology: Using Maps to Find "Lost" Sections

Honesty time: most of the "wall" isn't a wall anymore. It's a mound.

👉 See also: Atlanta Georgia Flight Departures: What Most People Get Wrong

In 2009, the Chinese State Administration of Cultural Heritage did a massive survey using infrared and GPS. They found about 180 miles of wall that nobody even knew existed because it was buried under sand dunes. If you're using a China wall in map search to plan a trip, don't just trust the green lines labeled "Great Wall."

Instead, switch to satellite mode.

Look for the shadows.

The wall is often easier to find by the shadow it casts in the morning or late afternoon rather than the structure itself. In the Ningxia region, the wall is almost invisible from a top-down 2D map, but the topographical 3D view reveals the distinct ridge of a 500-year-old defensive line.

Why the Map Doesn't Tell the Whole Story

A map is a flat representation of a 3D nightmare. The wall doesn't just go left to right; it goes up and down at angles that would make a mountain goat nervous. Some sections are built on ridges that are nearly 3,000 feet above the valley floor. When you see a China wall in map coordinate, it doesn't convey the fact that the "path" is actually a crumbling staircase where each step is two feet high.

William Lindesay, a famous British explorer who has spent decades mapping the wall, often points out that the "Ming Wall" is just the most recent layer. Maps often fail to distinguish between the Ming structures (the stone ones we know) and the much older Han or Qin dynasty walls. Those older walls are often miles away from the "official" map markers, sitting silently in the middle of nowhere.

Navigating the Wall Digitally and Physically

If you’re trying to actually visit these coordinates, standard Western maps like Google can be a bit... off. Due to the "GPS shift" in China (a security mess involving the GCJ-02 coordinate system), your blue dot might appear to be 500 meters away from where you’re actually standing.

For a true China wall in map experience, you’re better off using local apps like Amap (Gaode) or Baidu Maps. They have significantly more granular data on the smaller watchtowers, which are often the best parts to see. These towers were signaling stations. They aren't just random bumps; they were part of a sophisticated smoke-signal "internet" that could send messages across China faster than a horse could gallop.

- Shanhaiguan: Where the wall "drinks" from the sea.

- Panjiakou: The underwater wall. Yes, part of the wall is literally submerged in a reservoir. You can see it on satellite maps as a ghostly line under the blue water.

- The Loop at Niangziguan: A strategic mountain pass that maps show as a complex knot of fortifications.

Practical Steps for Map Enthusiasts and Travelers

If you want to master the China wall in map research phase, stop looking for a single line. Instead, focus on "Passes" (Guan). These were the gates where trade happened. Search for names ending in "-guan" like Juyongguan or Yanmenguan. These are the anchors of the map.

Next, use "Terrain" view. The wall follows the highest ridges. If the map shows a line crossing a flat valley, it’s probably a modern reconstruction or a trench. The real ancient wall hugs the peaks because that was the whole point—to make it impossible for an army to climb.

Finally, check the "Street View" or user-uploaded 360 photos. In China, these are everywhere. They give you the "ground truth" that a satellite can't. You'll see if a section is "Wild" (overgrown with trees and crumbling) or "Restored" (neatly paved with souvenir stands).

The best way to engage with the Great Wall is to realize it's a living ruin. It’s disappearing. Every year, wind erosion and human activity shave a little bit more off the western sections. Mapping it isn't just about navigation; it’s about documentation before the desert takes it back.

To get started with your own digital exploration, start at the coordinates 40.4319° N, 116.5704° E. That’s Mutianyu. Zoom out slowly. Follow the ridgelines to the west. Don’t look for the road; look for the spine of the mountain. That’s where the history is hiding.

Find a section that looks interesting and cross-reference it with historical records or topographical data to ensure it's a safe and legal area to visit. Many "unmapped" sections are protected or too dangerous for casual hiking, so always prioritize local regulations over a cool map coordinate.