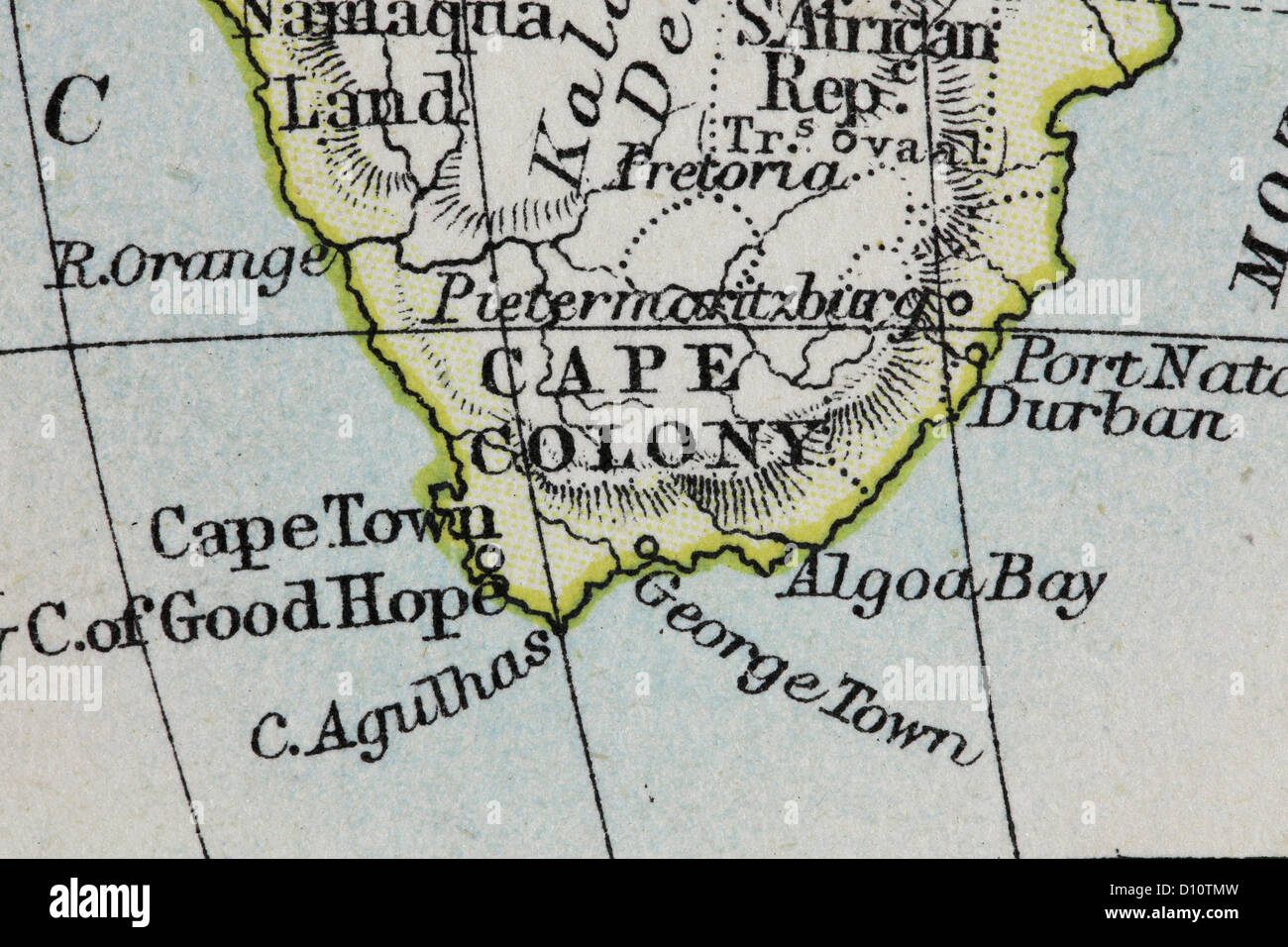

You’re looking at a map of the world. Your eyes drift down past the equator, past the dense jungles of the Congo, and all the way to the jagged, tapering end of Africa. There it is. A tiny sliver of land often mistaken for the very bottom of the continent. If you want to find the Cape of Good Hope map on the world map, you have to look just slightly to the west of the actual southernmost point. It’s a common mix-up. Most people point to that sharp corner and think, "That’s the end of the world."

It isn't.

That honor actually goes to Cape Agulhas, which sits about 150 kilometers to the east-southeast. But honestly, the Cape of Good Hope is the one that captured the world's imagination. It’s the legendary "Cape of Storms." It’s the place where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans supposedly clash in a violent spray of salt and myth. If you’re trying to locate it precisely, its coordinates are $34^\circ 21' 29'' S, 18^\circ 28' 19'' E$. It’s a narrow, rocky peninsula that defines the southwestern edge of the African continent.

Why the Cape of Good Hope Map on the World Map is Often Misunderstood

Maps are liars. Or, at least, they’re approximations. When you zoom out to a global scale, the Cape of Good Hope looks like a sharp needle piercing the southern ocean. Because of the way Mercator projections work, the sheer scale of the trek from Europe to this point is often lost on us. To the early Portuguese explorers like Bartolomeu Dias, this wasn't just a coordinate. It was a wall.

When Dias first rounded it in 1488, he didn't call it the Cape of Good Hope. He called it Cabo das Tormentas—the Cape of Storms. King John II of Portugal, who was a bit of a PR genius, renamed it because he wanted to encourage trade. He needed people to believe that passing this point meant they were finally on their way to the riches of India. "Good Hope" was basically a 15th-century marketing campaign.

But if you look at a modern Cape of Good Hope map on the world map, you’ll see it’s part of the Table Mountain National Park. It’s a protected wilderness. It’s not just a rocky cliff; it’s a biodiversity hotspot. There are plants here—fynbos—that grow nowhere else on the planet. Literally nowhere. You can walk through a patch of scrubland the size of a backyard and find more plant species than there are in the entire United Kingdom.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

The Great Ocean Debate

One of the coolest things about spotting this location on a map is the intersection of the currents. People love to say this is where the cold Atlantic meets the warm Indian Ocean.

It’s a bit more complicated than that.

The actual meeting point fluctuates. It moves back and forth between Cape Agulhas and Cape Point. The Agulhas Current (warm) and the Benguela Current (cold) dance around each other. From a high vantage point on the Cape, you can sometimes see the distinct colors of the water shifting, a visual boundary that feels like you're staring at the edge of a planetary gear system. It’s messy. It’s chaotic. It’s exactly why so many ships ended up at the bottom of the sea here.

Navigation and the History of the Southern Tip

Why do we care about a map of this specific spot? Because for centuries, this was the most important turn in the world. Before the Suez Canal opened in 1869, if you wanted pepper, silk, or tea, you had to go around this rock.

- 1488: Bartolomeu Dias proves the Atlantic connects to the Indian Ocean.

- 1497: Vasco da Gama successfully navigates the route to reach India.

- 1652: The Dutch East India Company (VOC) sets up a "refreshment station" which eventually becomes Cape Town.

The Cape of Good Hope isn't just a geographical feature. It’s a graveyard. The "Flying Dutchman" legend originated here—a ghost ship doomed to sail these waters forever, never quite rounding the headland. Even today, with modern GPS and massive steel hulls, sailors respect these waters. The "Roaring Forties"—strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere—hit the African landmass right here, creating massive swells.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

Finding it Today

If you're using Google Maps or a physical atlas, look for the "Cape Peninsula." It looks like a long finger pointing south from the city of Cape Town. At the very tip of that finger, it splits. One side is Cape Point (where the lighthouse is) and the other is the Cape of Good Hope.

Walking between them is one of the most surreal experiences you can have. You’ve got ostriches roaming the beaches. There are baboons that will absolutely steal your sandwich if you aren't looking. It feels wild. Despite being just an hour's drive from a major metropolitan city, it feels like the edge of the world.

Practical Insights for Modern Explorers

If you are planning to visit or just studying the Cape of Good Hope map on the world map for a project, keep these specific details in mind. Don't just look at the dots; look at the terrain.

1. Don't confuse it with Cape Point.

They are in the same reserve, but they are different landmarks. You can hike between them in about 45 minutes. Cape Point is higher and has the iconic lighthouse, but the Cape of Good Hope is the actual geographical "Cape" mentioned in the history books.

2. Watch the Weather.

The map doesn't show the wind. The "South-Easter" wind can get so strong it can literally knock a person over. If you're visiting, check the wind speeds. Anything over 40 km/h makes the cliff edges a bit spicy.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Your Way: The United States Map Atlanta Georgia Connection and Why It Matters

3. The Biodiversity Factor.

The Cape Floristic Region is the smallest and richest of the world’s six floral kingdoms. This is a massive deal for ecology. When you look at the map, remember that this tiny area holds about 9,000 plant species, 69% of which are endemic.

4. Seasonal Timing.

If you want to see the "meeting of the oceans" vibe, go in the winter (June to August). The storms are more dramatic. If you want to see the flowers, go in the spring (September to October).

5. Real-World Navigation.

If you're flying in, you'll land at Cape Town International (CPT). From there, you take the M4 or the much more scenic Chapman's Peak Drive (M6). Chapman’s Peak is widely considered one of the most beautiful marine drives in the world, carved directly into the side of the mountains.

The Cape of Good Hope remains a symbol of transition. It’s the point where the journey changes direction. Whether you are looking at it on a pixelated screen or standing on the weathered rocks feeling the spray of the Atlantic, it represents the human urge to see what’s around the next corner. It’s not the end of Africa, but it is certainly the beginning of a different world.

Next Steps for Your Research:

To get a true sense of the scale, open a satellite view of the Cape Peninsula. Zoom in until you see the white foam of the waves hitting the rocks at the Cape of Good Hope. Notice the kelp forests—they look like dark patches in the turquoise water. These forests are vital to the ecosystem and were featured heavily in the documentary "My Octopus Teacher," which was filmed in these very waters. If you're studying the maritime history, look up the "Saldanha Bay" charts to see where ships used to hide from the storms before making the turn.